Vania M. Smith1

11 Stetson J. Advoc. & L. 238 (2024)

Contents

- I. Introduction

- II. Trial Competition Structure and Rules

- III. Background, Training, and Virtual Courtroom Conduct of Judges and Evaluators

- IV. Competition Scoring Rubrics

- V. Online Competitions and the Infiltration of Courtroom Drama

- VI. Proposal to Promote Practical, Authentic Trial Competitions

- 1. Changes to the Structure, Rules, and Conduct of Trial Competitions

- a. More Realistic Approach to Trial Preparation

- b. Support for Trying the Case in Front of You

- c. Allow More External Case Law

- 2. Changes to the Background, Training, and Virtual Courtroom Conduct of Judges and Evaluators

- a. Utilizing the Practical Experience of Trial Lawyers

- b. Effective Orientation and Training Strategies

- c. Addressing the Attentiveness of Evaluators in the Virtual Courtroom

- 3. Shift to Scoring What Matters

- VII. A New Sample Rubric

- Footnotes

- Downloads

Like other forms of entertainment, “what television touches it distorts,” and it turns the serious business of adjudicating legal disputes into something that appears to be much more entertaining than it really is.2

I. Introduction

Trial advocacy education aims to train the next generation of trial lawyers to be effective communicators, story tellers, and persuasive advocates. In law school trial advocacy programs, the central mission is working with students on presentation skills required to effectively communicate in the courtroom and connect with juries. These skills are important to graduate practice-ready trial lawyers. Teaching these skills in the classroom and in clinical courses, however, can be vastly different from how these skills are coached to succeed at mock trial competitions. Advocacy and tactics employed to win at the highest levels can come at the expense of modeling the authenticity, attention to detail, and practical skills that are vital to the ongoing integrity of the profession and the maintenance of courtroom decorum.

The comparison of professional arenas to the theatrical stage is not new. In the medical profession, the operating room has a history of being called the “theater”.3 The same is true for the courtroom. The well of the courtroom is likened to a stage. The witnesses are compared to actors as they tell their story of what occurred. The judge is the director who sets forth how the various participants will move about the proceedings. The lawyer is the producer who brings the story to the jury. The jury is the audience that receives the information being presented and offers its “review” in the form of a verdict. There is no question that there are theatrical elements in the production of a modern trial. “[A] courtroom is a theatrical space that comes loaded with hefty expectations from the audience.”4

In response to these expectations, many law firms employ professional coaches with backgrounds in theater to teach trial lawyers storytelling techniques that will lead to more persuasive arguments. One such organization, KNP Communications, based in the Washington D.C. metro area, employs a team of experts with varying backgrounds (including theater veterans who lead the organization’s Legal Training practice) to coach lawyers and other professionals on effective presentation, public speaking, communication and persuasion. This type of instruction has value, particularly in the training and development of new associates who are recent law school graduates. New trial lawyers who graduated at the top of their class and excelled in doctrinal courses may have struggled with public speaking anxiety or persuasiveness, never participated in moot court or mock trial, or participated in these activities and gained some elements of insincerity and inauthentic advocacy while being coached simply to win. A genuine problem arises when mock trial coaches at the law school level inject extreme theatrics, insincerity, and melodrama into team presentations at trial for the purpose of winning by entertaining, to the detriment of sound advocacy skills. Students are taught winning theatrical tools rife with insincerity. “What is problematic about these devices is that they all involve the teaching of insincerity without bringing that fact to the students’ attention.”5 While these types of performances may be exciting, compelling, and competition winners; these victories come at the expense of the core mission of trial advocacy education: producing authentic, real-world, practice-ready trial lawyers.

Modern society is largely driven by social media, entertainment, and pop culture. It is not surprising that entertainment spills over into professional settings. The courtroom is no exception. In discussing the influence of popular culture on society’s perception of courtrooms, it is noted that “[j]urors have come to expect the excitement and drama of popular culture’s fictional depictions of courtrooms, and when such performance is not delivered, jurors become disenchanted with the system, and the attorney who failed to employ such tactics will likely face an adverse outcome.”6 While some element of theatrics, drama, and passion is helpful in creating connection; rewarding an entertaining advocate irrespective of the advocate’s mastery of the rules of evidence, effective cross-examination, the proper use of demonstratives, and the art of ’trying the case in front of you’ does a disservice to law students, the academy, and the legal profession. The Florida Rules of Professional Conduct admonishes lawyers against needlessly theatrical performances, stating that an attorney must maintain “…and preserve professional integrity by patient firmness no less effectively than by belligerence or theatrics.” 7 The global pandemic that began in 2020 drove many existing trial competitions to online formats, and also birthed new competitions to take advantage of an inexpensive, travel-free way to expose more students to the benefits of trial competition. However, amid this innovation, students were forced into miniscule boxes on screens. This triggered the infiltration of needlessly dramatic, inauthentic, television-style advocacy as teams struggled to find ways to connect with an often unseen audience on the other side of the camera. As a result, many students were not zealously advocating for their clients, they were not conducting themselves as real-world trial lawyers, they were engaging in courtroom cosplay . . . and in some cases, it was rewarded.

As the mock trial world returns to in-person trial competitions, online and hybrid competitions may be here to stay and could be a part of trial advocacy education moving forward. How do educators ensure that trial advocacy education delivered through participation in mock trial competitions reflects the authenticity needed to produce practice-ready trial attorneys? This article posits that the solution lies in changes to the structure and rules governing trial competitions, the background, training, and virtual courtroom conduct of competition evaluators, and the scoring rubric used to evaluate competitors. The article will first explain the general structure of and rules for in-person and online trial competitions. Next, it will discuss the background, training, and virtual courtroom conduct of trial competition judges and evaluators. Then, it will explore the rubrics used to evaluate the performances at trial competitions. After setting the backdrop of the mock trial world, the article will explore how the shift to virtual competitions spawned issues related to authenticity and overly dramatic, theatrical trials. Finally, the article offers solutions to address the issue of authenticity in mock trial advocacy. This article will focus solely on mock trial competitions, to the exclusion of moot court, arbitration, voir dire, and other specialty competitions, and uses as a frame of reference two current national competitions: The Texas Young Lawyers Association/American College of Trial Lawyers National Trial Competition (“NTC”) and The American Association for Justice National Mock Trial Competition (“AAJ”)

II. Trial Competition Structure and Rules

Trial competitions, though varied, follow a similar format. Skilled practitioners, law professors, and mock trial coaches develop intricate case packets with a collection of depositions, physical evidence, and supporting documents, which are released to competing schools about six weeks before the start of the first round of competition. Two of the most highly regarded competitions in this space are NTC and AAJ. These two competitions follow a similar format. There are regional competitions around the country where a winner or two (in the case of NTC) advance to the national competition. Students compete on teams of two to four students, with two students serving as the advocates trying the case. On teams of four, the other two students portray witnesses. Each student is tasked with either an opening statement or closing argument; one direct examination and one cross-examination. Students must also make objections and respond to evidentiary arguments. Witnesses are either portrayed by members of the competing teams who are not serving as advocates or are provided by the competition hosts.8

Competition rules are provided to the competitors at the release of the competition case file. The rules provide the necessary structure for the competition and address the regional nuances in trial practice to promote a sense of parity going into the competition rounds. Currently, the rules do not address authenticity, theatrics, melodrama, or memorization; however, there are rules that address the conduct of students appearing as witnesses. The All-Star Bracket Challenge, an online competition first held in 2020 notes:

On cross-examination, witnesses must be responsive to the questions and respectful of their opponent’s time limit. Where the truthful answer to a question is simply yes or no, that should be the answer. Excessively long answers are bad faith behavior, and judges will be instructed to penalize teams with ’advocate witnesses.’9

Rules against advocate witnesses notwithstanding, witnesses are encouraged to immerse themselves in the role being portrayed and display a thorough knowledge of the facts pertaining to their testimony.

Rules related to the general style and manner of trial competitions and the use of technology vary based on the type of competition. In-person competitions utilize law school courtrooms and classrooms for most preliminary rounds, and when available, municipal courthouses are used for the later rounds. While there is no rule requiring it, the normal practice is for students to conduct the trial standing, moving freely about the courtroom. For in-person competitions, the use of technology has been largely prohibited as varying courthouses and other competition venues have disparate facilities. For these competitions, students will often distribute copies of printed exhibits to the jury or display physical enlargements on easels. Dry-erase boards and overhead projectors (ELMOs) are also used.

For virtual competitions, students have competed from their homes, often using a blank wall or virtual background as a backdrop, or competed in the courtrooms located at their respective law schools. To “appear” in the virtual courtroom, external video feeds or webcams are used. As different types of equipment vary in quality, so too do the images of the advocates as shown on the screen. During the course of the trial, advocates are permitted to use the screen share feature in the virtual courtroom to display exhibits. Additionally, students may use digital presentation software to create demonstratives, slide shows, or play audio-visual evidence.

III. Background, Training, and Virtual Courtroom Conduct of Judges and Evaluators

Mock trial competition judges and evaluators are recruited from the legal community. Judges, lawyers, law professors, and trial coaches volunteer to serve as the presiding judge or on a panel of evaluators. At the national level, NTC uses members of the American College of Trial Lawyers as judges and evaluators for the semi-final rounds, and a full panel of up to 30 members for the national final. Some smaller, specialty competitions use lay jurors in addition to legal professionals.10 Recruitment is handled by the competition hosts, often pulling from the local legal community, particularly when the competition is in-person. Online competitions have a more national reach, with evaluators able to participate from their computers, from any location around the world. With no in-person requirement, the pool of available volunteers expands, and there are more judges and evaluators available to participate.

Competitions are typically held over three to four days, starting on either Thursday or Friday and culminating in a final round on Sunday. In the days leading up to the competition, judges and evaluators receive logistical information and the competition rules. Upon arrival, they also receive the score sheets for each round. Prior to the start of the first round, presiding judges are often given a bench brief and participate in a meeting to review the competition rules and discuss potential evidentiary matters that may arise. No formal evaluator training or orientation is required. Once all the competitors and evaluators are present in the courtroom, the final step is a conflict check to ensure that none of the judges or evaluators know any of the competitors or have any other affiliations that would raise a fairness issue. For virtual competitions, prior to the start of each round, the judges and evaluators are admitted to the virtual courtroom and are given brief instructions on how to set their screens to different views during the competition. Generally, judges are instructed to remain on screen for the duration of the trial, except for opening statements and closing arguments. Evaluators are off-screen for the entire trial (including pre-trial matters) and only appear to the participants to provide feedback after score sheets have been turned in and verified.11

IV. Competition Scoring Rubrics

Mock trial competitions employ numerical rubrics to rate and rank the performances of the advocates. These scoring models can be elaborate, with different mechanisms in place for handling tiebreakers and addressing rule violations that may arise. The scored components of most competitions include: opening statements, direct examinations, cross-examinations, and closing arguments. Evaluators are also permitted to provide substantive comments to the competitors in addition to numerical scores. Judges and evaluators are asked to focus their comments on the advocacy, and not the facts of the case file.12 Motions in limine, evidentiary arguments, and mid-trial motions (where permitted) are not scored. Scoring rubrics are readily available on some competition websites and are often used by trial team coaches in preparing their students for competition.

V. Online Competitions and the Infiltration of Courtroom Drama

The global pandemic ended in-person instruction for most law students in late March of 2020. Once it became clear that the pandemic would extend far beyond that spring, the organizers of national competitions began the pivot to hosting competitions online. Early on, the logistics and rules of the competitions remained consistent with the prior norms, with only small technical exceptions. Students adapted quickly and began to use available technology to produce visually appealing demonstratives and adjust to the new platform. What no one seemed to have predicted, however, was the way the change in format would influence how teams presented their cases as advocates.

As students began to learn advocacy solely via online instruction and, in turn, use what they learned to prepare for trial competitions, there appeared to be a desperate need to stand out in a new mock trial environment comprised of boxes on a screen. Without the ability to move about the courtroom, make eye contact with an evaluator, or use body language during examinations to set the tone and establish command of the courtroom, advocates were, in some ways, forced to resort to theatrical tactics. Some of the tactics were subtle in the beginning: the use of elaborate screen backgrounds and lighting to create a dramatic, film-like effect, or using demonstratives with sound and high-end graphics as opposed to more traditional white-board demonstrations; but as the pandemic wore on, more elaborate theatrical tactics were employed, including excessive hand gestures that were relatively comparable to pantomime, the use of animations over the image of the advocate while presenting their case, similar to a sports ticker on the bottom of the screen, and variations of body position and vocal volume that could best be described as over-the-top. In a recent discussion, a panel of judges expressed their frustration with some of the theatrical tactics attempted in their courtrooms. The panel advised that “courtroom theatrics are discouraged.” “…[S]winging baseball bats [and] overdramatic facial expressions… [are some of] the various ways lawyers can fall from favor in the courtroom.”13 This shift occurred at the same time that the pool of volunteer judges and evaluators expanded, as volunteers were now able to assist from home. These evaluators, many of whom were new to judging mock trial competitions, appeared to be swayed by dramatic performances:

[t]he entertainment nature of television, film, and print creates a problem with the accurate portrayal of a trial. This is evident considering that jurors and non-legal commentators alike react to a lawyer’s performance in court, drawing correlations to images and prototypes based upon fictional works of art.14

This influence of television and popular culture is so ingrained in our society that one cannot assume courtrooms are immune. In the mock trial world, particularly during virtual competitions, a more traditional, practical team is often no match for a more theatrical team. “Television and movie viewers have grown accustomed to professional actors making flawless presentations, which in turn raises their expectation on how the litigators are to perform in the case in which they are trying.”15 When evaluators don’t get the level of drama they expect from one team, and the other team provides dramatic excitement, the more traditional team is at a marked disadvantage.16

VI. Proposal to Promote Practical, Authentic Trial Competitions

The proposed solution to address the concerns raised about authenticity in trial competitions has three components: 1) Changes to the structure, rules, and conduct of trial competitions, 2) Changes to the background, training, and virtual courtroom conduct of judges and evaluators, and 3) Changes to the scoring rubrics used at trial competitions.

1. Changes to the Structure, Rules, and Conduct of Trial Competitions

a. More Realistic Approach to Trial Preparation

In the universe created by a mock trial competition case file, the lengthy work of discovery, pre-trial motions, depositions, crime scene re-creation, etc., has all been completed. Students are given clean exhibits and are prohibited from inventing facts, arguing outside case law, or adding exhibits to the case file. Of the competitions that are the focus of this analysis, only NTC allows the use of outside case law, and that use is limited to evidentiary arguments. 17 Because of this, students are handed a complete case that is ready for trial. To provide a more realistic experience, trial competitions should provide students with a smaller window to prepare. Instead of allowing five to seven weeks, cutting that time to three to five weeks would go a long way towards ensuring a more realistic experience and a competition that is more focused on practical trial skills. With less time, students would be less likely to use precious, limited preparation time to craft elaborate, overly dramatic arguments that take away from their use of sound advocacy skills.

b. Support for Trying the Case in Front of You

The change to allowing less time for packet preparation also gives rise to the next proposal. End the practice of rewarding memorization. Complete scripting and memorization should rightfully end with the Opening Statement. The Opening Statement is the opportunity to lay out a version of the facts of the case to the jury to a level of detail that, by necessity, requires clear, vivid storytelling, however, storytelling does not equal theatrics. After Opening Statements, students must learn the very practical skill of ’trying the case in front of them.’ It is impossible, even given the small universe created by the competition case file, for any team to anticipate every possible argument, presentation style, motion, and nuance of the opposing side’s case. Because of this, mock trial competitors, like real-world trial lawyers, must be forced to exhibit the deep knowledge of the case that is only displayed by adapting to the trial in real-time. Removing the stigma of having a legal pad to jot down and read back testimony that was just given on direct examination in an effective cross-examination is an opportunity to signal to students that a trial is not a performance. As courtrooms embrace technology, more trial lawyers (and their new associates sitting second chair) are using tablets and laptops in real-time to conduct searches of facts in the case file that come up at trial, recall exhibits they had not planned to use or to research a particular point of case law an opposing team is arguing that perhaps they had not considered. This is all practical lawyering and should be seen as elite, next-level law student advocacy. These are the skills that trial team coaches should be teaching, and trial competitions should be rewarding.

c. Allow More External Case Law

In addition to allowing less time for packet preparation and de-stigmatizing the use of notes and technology, trial competitions should also universally allow the use of external federal case law when students are advocating. There is no trial court in the country where this practice is prohibited, and limiting the use of case law only to federal law prevents teams from using obscure, niche, state-specific law in their arguments. It is not too extreme to state that the failure to research and argue appropriate precedent that has a bearing on the case is a failure to zealously advocate on behalf of the client. Particularly as it relates to evidentiary arguments, it is far more realistic to allow students the intellectual freedom to take the scenario of the case file and apply it to established law. The ability to read a set of facts and then later interpret those facts through the lens of established case law is what trial lawyers are charged to do daily. Requiring this skill in mock trial competitors would only serve to enhance the educational experience.

2. Changes to the Background, Training, and Virtual Courtroom Conduct of Judges and Evaluators

a. Utilizing the Practical Experience of Trial Lawyers

Trial competition judges and evaluators are currently recruited from the legal community without limitation. Lawyers need not be trial lawyers, law professors, or trial coaches to sign up to participate. This is done out of necessity. It is very difficult to recruit judges and evaluators as this is fully a volunteer exercise that typically requires a minimum three-hour commitment, largely on weekends that are very precious to practicing attorneys. Despite this, it is critical that judges and evaluators have a real, practical knowledge of the proper conduct of trials, the rules of evidence, and the art of courtroom storytelling. To preserve the educational value of trial competitions and avoid evaluators who may be unduly influenced by the aforementioned infiltration of pop culture into the perception of effective advocacy; concerted efforts should be made to recruit judges and evaluators who have a practical background in trial advocacy beyond classroom theory. Sitting and retired judges, district attorneys and public defenders, civil litigators, clinical professors of trial advocacy and the like have the most current, practical pulse on what is acceptable in our courtrooms, and what constitutes a departure from authentic advocacy. Using practitioners with real courtroom experience can lead to a shift in focus to rewarding practical skills.

Similarly, competitions that currently use lay witnesses should consider ending that practice. Yes, law students do need to be prepared to advocate in front of real juries when they begin practicing; however, the use of lay witnesses at trial competitions can have a negative impact on the educational experience which should be the main objective of the competition. As discussed previously, the influence of pop culture on lay understanding of the proceedings of a courtroom cannot be ignored. The risk of having competitions evaluated by the public, yearning for a “Legally Blonde gotcha moment”18 or waiting to hear “you can’t handle the truth”19 yelled at a witness, is high. Mock trial coaches, under pressure to ensure their programs are well funded and supported by the administration, will inevitably have to focus on what wins in these scenarios, not what is best for the educative process.

b. Effective Orientation and Training Strategies

Volunteering to judge or evaluate a trial competition is a time commitment outside of the presumably busy schedule of a legal practitioner. It is the goal of every trial competition to make the process of judging as seamless as possible and to retain potential judges and evaluators for future competitions. The last thing a competition organizer wants to do is to add to that commitment by requiring orientation or training. Unfortunately, it is necessary. Judges and evaluators are not as immersed in the mock trial competition world as coaches, teams, case file authors, or competition organizers. As a result, their understanding of what should be evaluated and what should be ignored is limited. A brief orientation to review the scoring rubric, discuss the concept of reasonable inferences, address a desire to allow students to use notes, legal pads, and technology; and openly address the need to evaluate the practical legal skills displayed by the competitors over the entertainment factor is critical. This can be accomplished by sending the judges and evaluators a brief letter or PowerPoint presentation that addresses these matters, or by requesting that they report to the live or virtual courtroom 15 minutes before the start of the trial for a briefing by the competition organizers. Taking the time to orient the judges and evaluators to the competition’s objectives can yield a measurable return on investment. If trial competitions are truly educational exercises, organizers, professors, and coaches cede a great deal of the messaging to students to the evaluators. A student’s most vivid memory of their participation in these competitions is their final rank or score. The score is what validates their preparation and performance. If that score is unduly high because an evaluator was entertained or swayed by theatrics, the entire objective of the experience is diminished. Taking the time to empower judges and evaluators with the tools they need to score objectively and effectively is a critical component of preserving the integrity of these competitions.

c. Addressing the Attentiveness of Evaluators in the Virtual Courtroom

Finally, there exists an issue with the conduct of evaluators while in virtual courtrooms. While all the other components of these proposals are apropos for both in-person and virtual competitions, this concern is directly related to the virtual platform. In current virtual competitions, evaluators are required to keep their cameras off for the duration of the competition after the pre-trial conflict check. This means that during all examinations, as well as opening statements and closing arguments, students are advocating without seeing the faces of the very individuals who will evaluate their performance. Because virtual competitions were the exclusive format for at least the first two years of the global pandemic, many law student advocates graduated in 2022–23 have never had the opportunity to deliver an opening statement or a closing argument while learning the very valuable and practical skill of reading the faces of the jury to determine if points are landing, and to establish a connection. If virtual competitions continue, to address the issue of connectedness, evaluators should keep their cameras on during opening statements and closing arguments (at a minimum), and advocates should shift their screen view to gallery mode so that they can truly argue to an audience.

This shift will also help address another problem that arises during virtual competitions: the lack of attentiveness of the evaluators. Evaluators who judged virtual competitions from 2020–23 have admitted to enjoying the flexibility of volunteering from their homes, and the ability to ‘multi-task’ while doing so. On some occasions, an accidental touch of a button has unmuted microphones and activated cameras to reveal evaluators caring for children, cooking, doing laundry, or other seemingly small tasks that undoubtedly affect their ability to provide the students with their attention as they would in a live courtroom setting. Prior to the global pandemic, mock trial competitions were conducted in person for decades, always with enough volunteers to complete the task at hand. Making this small change to evaluator conduct may reduce the volunteer pool but should not take it any further than to pre-pandemic levels.

3. Shift to Scoring What Matters

The most important change needed to mock trial competitions is a change to the scoring rubric. Competitions should evaluate and score what matters: authenticity, a working knowledge of the Federal Rules of Evidence, agility, and adaptability at trial, proper courtroom mechanics (admitting evidence, qualifying an expert, conducting voir dire), thoughtful and illustrative direct examinations, direct and pointed cross-examinations, opening statements rife with unique storytelling, and persuasive closing arguments that effectively argue what was elicited at trial. This new rubric challenges the notion that an advocate can win with passion alone and elevates those aspects of trial advocacy that clinical programs purport are central to their mission. Providing this revised framework will also serve as clear guidance for trial coaches and program directors as they prepare their teams for competition, refocusing their attention on the fundamentals of practice and away from coaching only what wins.

Participation in mock trial competitions is a valuable, coveted part of the law school experience. Many employers, particularly litigation firms, look for this experience on resumes as they interview and select their new classes of associates. Trial advocacy educators and mock trial coaches have a responsibility to future trial lawyers to ensure the education they are receiving is in fact one that will prepare them to litigate in real courtrooms around the country under varying conditions. The spirit of competition is natural. It is woven into America’s DNA. Everyone wants to feel celebrated, have their accomplishments recognized, and reach the pinnacle of a chosen endeavor. That is understandable. However, trial advocacy programs should not take a “win at all costs” approach to the sacred task of training the next generation of trial lawyers. Their education and preparedness for the future must take precedence. The way to do that is to ensure that mock trial competitions reflect the real-world as much as possible. Celebrate effective storytelling, reward adaptability and the use of technology, encourage students to “try the case in front of them”, and, above all, reject theatrics and melodrama in favor of authenticity. What follows is a sample rubric that addresses the concerns raised by this article.

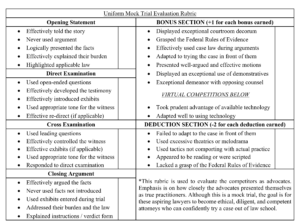

VII. A New Sample Rubric

Judges and evaluators are reminded of the following when scoring today’s competitors:

-

Judges and evaluators are not to consider the physical location/backdrop used by the student for the conduct of a virtual trial.

-

Judges and evaluators are not to consider the decision by a student to sit or stand while advocating during a virtual trial.

-

Judges and evaluators are reminded to evaluate students’ performances today based on translatability to and comportment with the reasonable conduct of an attorney in a courtroom.

-

Please score each element on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being the highest possible score.

-

In the bonus section, please check the box corresponding to each bonus the student has earned. 1 point is added for each.

-

In the deductions section, please check the box corresponding to each deduction the student has earned. 2 points are deducted for each.

-

Fractional points are only to be awarded in increments of (0.5).