Jules Epstein

Eyewitness error, the product of inadequate perception and/or failed or altered memory, is generally the ‘stuff’ of criminal procedure courses. “The vagaries of eyewitness identification testimony” language dates back to Justice Frankfurter, and courses on wrongful conviction remind students that in the DNA exoneration cases 70% or more involved the mistaken claim of “that’s the person.” But the lessons of eyewitness error are not limited to the practice of criminal law; and indeed are not limited to testimony in civil and criminal cases where a person is being identified. Rather, the lessons are those of the limits of memory in general, and as such need to be drawn upon when training our students (and ourselves) in better client and witness interviewing techniques (and in understanding why a courtroom account of an event may be a far cry from what actually happened months or years earlier).

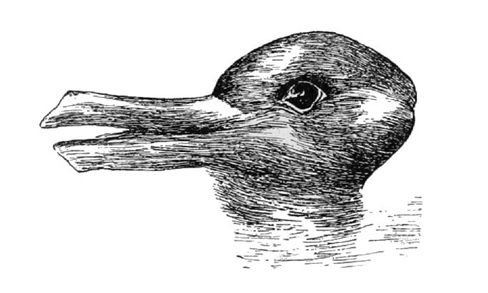

Take a look at the below image. It was made famous nearly 70 years ago by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his posthumous Philosophical Investigations (1953) to explain “aspect perception,” but was first used in 1899 by American psychologist Joseph Jastrow. When used in trainings for lawyers and investigators handling eyewitness-based cases, a blank screen is shown and the following instructions are provided: “I am going to show you an image for 3-4 seconds. Please make note of what you see.” The presentation advances to the next slide where the image appears, and after 3-4 seconds the screen goes blank. When the audience is asked “what did you see,” some see a duck but others a rabbit.

The lesson in eyewitness cases is easy – people see some details and miss others, and an identical object can have different meanings and appearances depending on the viewer’s predilections and orientation.

But wait. The title of this article is not “make note of what you see” but instead is “do you see the duck?” That adds a confounding problem, one that leads to better interviewing techniques. The problem here is simple – by suggesting what the observer will see, it creates an expectation. And when interviewers suggest what the witness recalls, it can do precisely that – creates a new memory.

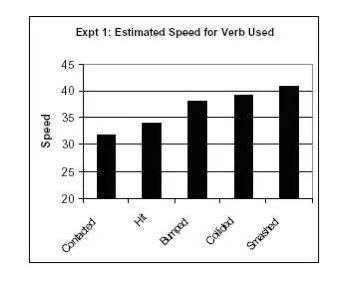

This second point is supported by now-legendary research by Elizabeth Loftus. Participants viewed a brief video of a car-on-car accident and then were asked one question: About how fast were the cars going when they (smashed / collided / bumped / hit / contacted) each other?” Different participants had different verbs. The results were stark – the more potent the verb, the faster the speed estimate:

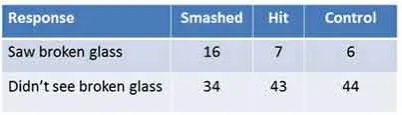

The problem did not end there. A follow-up interview conducted one week after the film was shown asked whether there was any broken glass. There was none in the film. A significant number of those who had been asked whether the cars “smashed” recalled broken glass.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/loftus-palmer.html (last visited July 15, 2021).

What are the lessons, then, for students when they study interviewing (and when they weigh how reliable deposition or trial testimony actually is when offered months or years after an event)? First come the general principles of memory science – perception is often inaccurate or incomplete to begin with, and even if a witness will never forget the gist of an event (who will ever forget September 11, 2001) that person loses detail memory within hours and then progressively over time (think 9/11 – which tower was hit first, and what airlines were involved).

With that fragility of memory comes the need for better modes of eliciting accurate memory. The rule is simple – don’t ask “do you see the rabbit” or “how fast were the cars going when they smashed?” Words trigger beliefs or affect perception. Instead, turn to more accurate modes of interviewing [note “interviewing,” not “interrogating”]. And this is where eyewitness research again offers tools for all forensic investigations – the cognitive interview.

Developed in the 1980 and 90s, the cognitive interview has various iterations but in its basic formulation has a series of stages:

- Establish rapport with the witness

- Let the witness first set the scene/environment (sometimes accomplished by asking the witness about general activities and feelings from the day at issue)

- Making an open-ended request for a narrative, letting the witness speak and later going back for details and follow-up

- Suggesting that the witness recount the events from more than one perspective, describing what they think someone else at the scene or even the perpetrator saw

- Asking the witness to tell the story backwards, from the ending to the beginning

- Instructing the witness to share all details, no matter how trivial

Is this actually better? In one study, test subjects observed a video of an event and then were questioned 48 hours later in one of three ways – a standard police interview, under hypnosis, or with the cognitive interview. In terms of the number of facts that were recalled accurately, the results were stark: on average, those with the cognitive interview recalled 41.2 facts, those under hypnosis 38, and those questioned in the typical police format 29.4.

Teaching about eyewitness error is critical as we explain the limits of trials and the weaknesses inherent in the criminal investigation process; but lessons from eyewitness research are memory lessons and should inform our teaching of witness interviewing and the limits of witness [or client] accuracy.

Special thanks to Temple Law Professor Ken Jacobsen, who teaches Interviewing and Negotiation; and University of Pittsburgh psychology Professor Jonathan Vallano, an expert in eyewitness memory and cognitive interviewing, for their critical input.

Resources:

For the latest book on the science of memory, see REMEMBER by Lisa Genova (https://www2.law.temple.edu/aer/can-we-trust-memory/)

For the original duck-rabbit research, see https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_54/January_1899/The_Mind%27s_Eye

For “aspect perception” see https://qrius.com/what-is-aspect-perception/

For the basics of cognitive interviewing see https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-interview.html

For how many details we forget, see Hirst et al, Long-Term Memory for the Terrorist Attack of September 11: Flashbulb Memories, Event Memories, and the Factors That Influence Their Retention, Journal of Experimental Psychology 2009, Vol. 138, No. 2, 161–176 https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2009-05547-001