Grant Rost: THE WORDS IN A SENTENCE OF GUILT

THE WORDS IN A SENTENCE OF GUILT

ORDER AS A FORM OF PERSUASION

Jules Epstein: ORDER AS A FORM OF PERSUASION

MATERIAL & METAPHOR

Grant Rost: MATERIAL & METAPHOR

LOVE CHOCOLATE AND STORYTELLING

Grant Rost: LOVE CHOCOLATE AND STORYTELLING

THE PERSUASIVE POWER OF UP

Grant Rost: THE PERSUASIVE POWER OF UP

IS A PICTURE INDEED WORTH THE PROVERBIAL THOUSAND WORDS?

Jules Epstein: IS A PICTURE INDEED WORTH THE PROVERBIAL THOUSAND WORDS?

WOULD YOU OR WILL YOU? QUESTIONING YOUR JURY AND SPARE TIRE.

By Grant Rost

It’s finally starting to get cooler and October is upon us. I think instantly of Keats’s poem, Ode to Autumn, in which he lovingly describes how the season itself conspires with the sun to produce fruit, and imagines the season, personified, sitting patiently by a cider-press to watch “the last oozings hours by hours.” I’m not nearly so winsome about the season. I am conspiring with my stomach to consume as many new pumpkin-spice flavored sweets as I can. My level of commitment to this annual task is quite real. In fact, last autumn, I found myself involved in a deep and meaningful conversation with one of Liz Lippy’s mock trialers over the wonders of pumpkin-spice flavored Frosted Mini-Wheats. By Christmas, I was oozing myself into jeans that weren’t nearly as loose as they were on October1st. A few weeks after Christmas I asked myself a New Year’s question: “Will you exercise?” Of course I will. “I will exercise!” I shouted into the void. I was wrong—about a great many things, actually.

In voir dire we might, often because of the pressure of a ticking clock, ask our jurors questions such as “Will you fairly consider the defenses we will raise against the claims here?” or “Will you presume throughout the trial that Dr. Jonathan Crane is innocent of the charges?” As it turns out, clock or no clock, science suggests we could be wrong about trying to secure commitments that way and there might be a better way—a brain way—to try to produce the fairness or presumptions we want.

Way back in 1980, a clever researcher by the name of Steven Sherman decided to run some interesting experiments on the citizens of Bloomington, Indiana.1 In one experiment, he had a researcher call up random numbers from the phone book. The people surveyed were asked one of two things. The first group was told that a survey was being conducted by the university because the researcher heard the American Cancer Society (ACS) was calling people asking for help. The researcher then asked, “If they called you, would you volunteer 3 hours to help them with their cancer research funding drive?” Three days later, the same people were called by a researcher posing as a solicitor from the ACS and asked if they actually would commit the three hours. None of those surveyed knew the two calls were related in any way. The second group, however, was called just by the presumed ACS solicitor and asked, “Will you help us by giving three available hours to our cancer research funding drive?”2

Of those in the latter group—asked immediately to volunteer—only 4% volunteered. However, those in the first group who were first asked to predict their later behavior…well, nearly half of everyone in that group predicted they would volunteer if asked. When they were ultimately asked to volunteer, 31% of everyone in this “make-a-prediction” group actually did volunteer. More importantly, 92% of those people who actually did volunteer on the second call were people who predicted they would volunteer!3 A rather startling number when one considers that only 4% of test subjects volunteered immediately without first making a prediction about their future behavior. The author attributes the high-percentage prediction of one’s later volunteerism to human beings following a kind of internal, moral script or “stereotyped response sequence” in which we humans will tend to over-predict our own moral goodness. If you’re saying to yourself, “Well, shoot, I recognize all this behavioral stuff as the self-fulfilling prophecy!” then you’re doing much better than Steven Sherman who decided 41 yearsago to call it “the self-erasing nature of errors of prediction.”

Now here is the fun part. Sherman is perhaps more whimsical than his hyper-technical word choice suggests. He conducted another experiment similar to that above. Here, one test group was asked to predict whether they would sing the Star-Spangled Banner over the telephone if they were later asked to do so on a different phone call. The second group was just asked to belt it out on the spot—no prediction. In the first experimental group, 44% predicted they would sing it and 40% of the group ultimately sang it when asked a few days later. However,a full 72% of those directly asked to sing it gave proof through the call that they were up to the musical task asked of them! I am sure you spotted a bit of a difference in singing as opposed to volunteering for cancer research: Those predicting whether they would volunteer for cancer fundraising were predicting their own moral behavior. Those predicting their willingness to sing were not following any similar moral “script.” By now, we can see the potential applications tothe formatting of questions on voir dire, so I need not spell it out for the trial lawyers in the room.

I must, however, and for the sake of my future autumn-involved, pumpkin-spice- consuming self, mention one related study. As you might imagine, marketers have seized on this self-fulfilling prophecy phenomena. A marketing professor at Washington State University conducted an experiment on people who had a gym membership but hadn’t attended their gym in at least a month.5 The first subject group in the experiment was asked if they expected (read: “predicted”) they would use the gym in the next 7 days. Like Sherman’s experiments above, the second experimental group was simply asked if they were members of a health club and not asked to predict anything. Researchers then tracked the gym attendance for both groups over the following week and then for 6 months afterward. 60% of those asked to predict their attendance said they thought they would attend the gym during that week. However, only 7% of those not asked to predict their attendance actually did attend the gym that week. Sherman’s study above helps us understand that over-estimated prediction of future good behavior. But here’s the whip cream on that slice of pumpkin pie: Over the next six months, those who were asked to predict their usage ended up using the gym twice as much as those who made no prediction at all!6

Yes, there is something wonderful and fascinating about autumn. The intermittent, trundling parade of Monarchs flying south, guided by some mysterious and magnetic pull. The brassy chimes of dry leaves stirred by northern winds. The last, sweet oozings from the cider press. Pumpkins.Spices for pumpkins. I am just going to say that I predict this fall will be no different from the last—andI will be full-filled.

Notes

- Steven J. Sherman, On the Self-Erasing Nature of Errorsof Prediction, 39 J. PERSONALITY & SOC. PSYCHOL. 211 (1980).

- See Id. at 217. I am really summarizing the spirit of the questions asked and not directly quoting the questions posed. Even Sherman doesn’t provide the words used for the questions posed to each group. I use “would you” and “will you” here to draw the distinction between being asked to predict and being asked to commit.

- Id.

- Id. at 218.

- Eric Spangenberg, Increasing HealthClub Attendance ThroughSelf-Prophecy, 8 MKTG.LETTERS 23 (1997).

- Id. at 27.

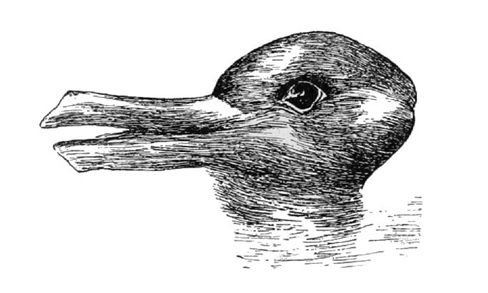

“Do you see the duck?”

Jules Epstein

Eyewitness error, the product of inadequate perception and/or failed or altered memory, is generally the ‘stuff’ of criminal procedure courses. “The vagaries of eyewitness identification testimony” language dates back to Justice Frankfurter, and courses on wrongful conviction remind students that in the DNA exoneration cases 70% or more involved the mistaken claim of “that’s the person.” But the lessons of eyewitness error are not limited to the practice of criminal law; and indeed are not limited to testimony in civil and criminal cases where a person is being identified. Rather, the lessons are those of the limits of memory in general, and as such need to be drawn upon when training our students (and ourselves) in better client and witness interviewing techniques (and in understanding why a courtroom account of an event may be a far cry from what actually happened months or years earlier).

Take a look at the below image. It was made famous nearly 70 years ago by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his posthumous Philosophical Investigations (1953) to explain “aspect perception,” but was first used in 1899 by American psychologist Joseph Jastrow. When used in trainings for lawyers and investigators handling eyewitness-based cases, a blank screen is shown and the following instructions are provided: “I am going to show you an image for 3-4 seconds. Please make note of what you see.” The presentation advances to the next slide where the image appears, and after 3-4 seconds the screen goes blank. When the audience is asked “what did you see,” some see a duck but others a rabbit.

The lesson in eyewitness cases is easy – people see some details and miss others, and an identical object can have different meanings and appearances depending on the viewer’s predilections and orientation.

But wait. The title of this article is not “make note of what you see” but instead is “do you see the duck?” That adds a confounding problem, one that leads to better interviewing techniques. The problem here is simple – by suggesting what the observer will see, it creates an expectation. And when interviewers suggest what the witness recalls, it can do precisely that – creates a new memory.

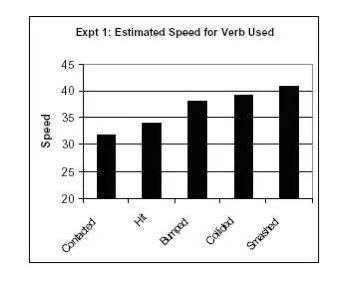

This second point is supported by now-legendary research by Elizabeth Loftus. Participants viewed a brief video of a car-on-car accident and then were asked one question: About how fast were the cars going when they (smashed / collided / bumped / hit / contacted) each other?” Different participants had different verbs. The results were stark – the more potent the verb, the faster the speed estimate:

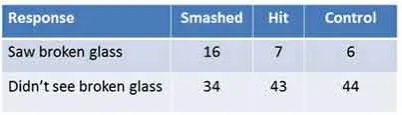

The problem did not end there. A follow-up interview conducted one week after the film was shown asked whether there was any broken glass. There was none in the film. A significant number of those who had been asked whether the cars “smashed” recalled broken glass.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/loftus-palmer.html (last visited July 15, 2021).

What are the lessons, then, for students when they study interviewing (and when they weigh how reliable deposition or trial testimony actually is when offered months or years after an event)? First come the general principles of memory science – perception is often inaccurate or incomplete to begin with, and even if a witness will never forget the gist of an event (who will ever forget September 11, 2001) that person loses detail memory within hours and then progressively over time (think 9/11 – which tower was hit first, and what airlines were involved).

With that fragility of memory comes the need for better modes of eliciting accurate memory. The rule is simple – don’t ask “do you see the rabbit” or “how fast were the cars going when they smashed?” Words trigger beliefs or affect perception. Instead, turn to more accurate modes of interviewing [note “interviewing,” not “interrogating”]. And this is where eyewitness research again offers tools for all forensic investigations – the cognitive interview.

Developed in the 1980 and 90s, the cognitive interview has various iterations but in its basic formulation has a series of stages:

- Establish rapport with the witness

- Let the witness first set the scene/environment (sometimes accomplished by asking the witness about general activities and feelings from the day at issue)

- Making an open-ended request for a narrative, letting the witness speak and later going back for details and follow-up

- Suggesting that the witness recount the events from more than one perspective, describing what they think someone else at the scene or even the perpetrator saw

- Asking the witness to tell the story backwards, from the ending to the beginning

- Instructing the witness to share all details, no matter how trivial

Is this actually better? In one study, test subjects observed a video of an event and then were questioned 48 hours later in one of three ways – a standard police interview, under hypnosis, or with the cognitive interview. In terms of the number of facts that were recalled accurately, the results were stark: on average, those with the cognitive interview recalled 41.2 facts, those under hypnosis 38, and those questioned in the typical police format 29.4.

Teaching about eyewitness error is critical as we explain the limits of trials and the weaknesses inherent in the criminal investigation process; but lessons from eyewitness research are memory lessons and should inform our teaching of witness interviewing and the limits of witness [or client] accuracy.

Special thanks to Temple Law Professor Ken Jacobsen, who teaches Interviewing and Negotiation; and University of Pittsburgh psychology Professor Jonathan Vallano, an expert in eyewitness memory and cognitive interviewing, for their critical input.

Resources:

For the latest book on the science of memory, see REMEMBER by Lisa Genova (https://www2.law.temple.edu/aer/can-we-trust-memory/)

For the original duck-rabbit research, see https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_54/January_1899/The_Mind%27s_Eye

For “aspect perception” see https://qrius.com/what-is-aspect-perception/

For the basics of cognitive interviewing see https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-interview.html

For how many details we forget, see Hirst et al, Long-Term Memory for the Terrorist Attack of September 11: Flashbulb Memories, Event Memories, and the Factors That Influence Their Retention, Journal of Experimental Psychology 2009, Vol. 138, No. 2, 161–176 https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2009-05547-001

MINIATURE GOLF, STEREOTYPE THREAT, AND SUPPORTING OUR STUDENTS

A number of college students were tested on their ability to play miniature golf. “All were told that they would complete a brief questionnaire, perform a sports test that was based on the game of golf, and then answer questions about their performance after the test was completed.” But one extra factor was added: Half were told the test was of “natural athletic ability [NAA]”; the others were told this was a measure of “sports intelligence [SI],” a.k.a. “the ability to think strategically during an athletic performance.”

The results were stark. White students who were told the test measured SI played golf better (23 stroke average) than those told it was a test of NAA (27 stroke average). Dishearteningly, Blacks who were told the test was for SI performed more poorly than those told it was testing NAA.

The study was Stone, J., *Lynch, C., *Sjomeling, M. & Darley, J. M. (1999). Stereotype threat effects on Black and White athletic performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1213-1227. But what does miniature golf have to do with law students studying advocacy or doctrinal subjects such as Evidence?

Look out at a law school advocacy classroom and (hopefully) you will be confronted with a sea of faces from diverse backgrounds. A natural reaction might be that since they all were accepted at law school, made it through first year, and now are 2Ls, they are all equally comfortable at the performance tasks we will be giving them. Perhaps we need to think again. Certainly we need to proceed with care and affirmation.

Valerie Harrison and Kathryn Peach D’Angelo, in their exceptional book DO RIGHT BY ME: LEARNING TO RAISE BLACK CHILDREN IN WHITE SPACES, explain that “Black students in a predominantly white school may feel pressure that white students do not experience to dispel the stereotype of intellectual inferiority. The extra pressure to succeed can…deplete the student’s memory[] or require energy to suppress negative thoughts, which means that less of the student’s energy and effort can be focused on the task.” Id. at 103-104.

The label for this phenomenon, studied for a quarter-century, is “stereotype threat.” It has been defined alternately as

• When people are aware of a negative stereotype about their group, they often worry that their performance on a particular task might end up confirming other people’s beliefs about their group. Psychologists use the term stereotype threat to refer to this state in which people are worried about confirming a group stereotype. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-stereotype-threat-4586395

• [N]egative stereotypes raise inhibiting doubts and high-pressure anxieties in a test-taker’s mind, resulting in the phenomenon of “stereotype threat.” Psychologists Claude Steele, PhD, Joshua Aronson, PhD, and Steven Spencer, PhD, have found that even passing reminders that someone belongs to one group or another, such as a group stereotyped as inferior in academics, can wreak havoc with test performance. https://www.apa.org/research/action/stereotype

Research studies have shown the following:

• When students were asked to note their race on a questionnaire prior to taking a vocabulary test, Black students scored lower than White students and lower than Black students who were not asked about their race. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-stereotype-threat-4586395

• When women were given a math test, some were told that men and women had performed equally well on this type of challenge and others were told that men and women scored differently. Those who received the latter type of information scored lower than those told that men and women did equally well. All were “top performers” in math. https://www.apa.org/research/action/stereotype

These are exemplary of numerous studies confirming the phenomenon of stereotype threat. They leave two questions. How can such threats be mitigated or removed; and is there anything in how we teach advocacy skills that might engender such threats?

Without studies in the law school (and skills course) contexts there aren’t specific proven preventive or ameliorative steps. But drawing from the numerous studies in other educational setting, some possibilities emerge. These include:

• Having a diverse faculty.

• Encouraging self-affirming reflections before or at the beginning of a semester. [One option is to ask every student to submit a paragraph or two listing what strength(s) or trait(s) the student believes will make them good advocates and to elaborate on why these are positives. This proposal models ones detailed in the Cohen et al paper listed in the resources section, below, and in the book THE GUIDE TO BELONGING IN LAW SCHOOL by Professor McClain.]

• Affirming abilities and performances.

• Showing videos or having demonstrations of skills using diverse students rather than only Whites.

• Having testimonials (live or video) of students of all backgrounds explaining how, even if difficult at the beginning of the course, they gained the skills and excelled.

• Finding video clips of more than My Cousin Vinny – whether Hollywood or actual trial recordings – where the lawyers are from diverse backgrounds.

• Making clear that the skills practices are not a test but a tool for learning. The same may be true with practice exams in doctrinal classes.

• Avoiding any messaging that certain skills are proxies for or correlate with intelligence or that might trigger concern over stereotypes (e.g., critiquing attire or speech patterns).

I don’t claim expertise here. There is more to be studied and learned, but one thing is beyond dispute. Stereotype threat is real, and ‘disabling’ and avoiding triggering it should be core to our teaching and coaching.

For more resources beyond those cited here, see

Claude M. Steele, WHISTLING VIVALDI, W.W. Norton & Co. (Norton 2010)

Russell McClain, THE GUIDE TO BELONGING IN LAW SCHOOL (West, 2020)

https://www.learning-theories.com/stereotype-threat-steele-aronson.html

http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/nov04/vol62/num03/The-Threat-of-Stereotype.aspx

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S002210310191491X?via%3Dihub

https://www.reducingstereotypethreat.org/home

Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Apfel, N. & Master, A. (2006). Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science, 313, 1307-1310, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6842991_Reducing_the_Racial_Achievement_Gap_A_Social-Psychological_Intervention

Mindset and Stereotype Threat: Small Interventions ThatMake a Big Difference

Posted By Marie K. Norman, PhD, and Michael Bridges, PhD On January 11, 2018 @ 5:52 am InDiversity and Inclusion,Motivating Students | https://www.occc.edu/c4lt/pdf/Faculty Focus _ Higher Ed Teaching and Learning Minds

Brain Lessons: The Consequence of Excising Emotion

by Grant Rost

Two weeks ago, my wife propped open the door of our (too-long-for-any-reasonable-use) screened porch. She was shuttling plants in and out every night and got tired of latching and unlatching the porch door. Well, it’s closed now—for good—because a hummingbird got into the porch. I can’t seem to forget that little bird and I thought I should write about him.

I saw him from the breakfast table. He was whizzing past the doors out to the porch, left and right, passing like a pendulum. Like every wasp and moth before him, he didn’t know how screens work—how they entice you with light and scenery but abruptly stop you with mesh. I went to try to herd him out the door. He just flew higher than my head and hands. Back and forth he went, missing the narrow porch door and smashing into the screens at each end. I got a pillowcase to try to catch him. It didn’t work. At one point in my end-to-end pursuit, I thought his tongue was lolling out of him, from exhaustion, but I quickly realized that he had irreparably damaged his delicate black beak. I made a fast and inexorable decision and I sent my wife back inside. Nobody needed to see the place where the two of us were going—fleeing and chasing.

I eventually caught him in the pillowcase. As I held him folded in the pillowcase, his squeakings, so familiar to me while I photograph them at our feeders, increased in tempo and timbre. I quickly picked up the nearest rock—and who knows why it was there on the deck outside—and put the whole affair to an end. The rest of the day, however, I just re-lived it…over and over. Our mutual helplessness. The sounds. The small red spot on the baby-blue pillowcase.

The rock.

I have been trying to ignore it. Ignore what? The emotion of the whole thing. Pushing it down, shooing it away and, finally, coolly rationalizing each of the events; or, to put it more honestly, my decisions within those events. Even as I write about it now, my eyes feel swollen with the press of tears that I’m blinking back. If I can’t be free of the memory, can I at least be free of the emotion that always arrives with it? Weeks have passed. Then, just tonight, I read about a man suffering from a small brain tumor who, upon the excision of the tumor, had no apparent capacity for emotion left within him. He was rendered emotionless. But, the surgery didn’t perfect him. It didn’t turn him into a most-intriguing rational razorblade, like Spock. As I read about him, I thought of my hummingbird and I knew what I had to write my June blog about.

Before his brain tumor, writes Jonah Lehrer, “Elliot” was a rather intelligent and successful man with a near genius IQ. Surprisingly, and despite losing a part of his brain to the surgery, he suffered no loss of intellect. He remained rational and high functioning in most respects. However, after his surgery those around him at work and home noticed two major differences: First, nothing seemed to touch him or move him. Not love, nor anger, nor fear. That’s expected when one loses one’s emotional senses. Now here’s the stunning part: Along with the absence of emotion, he seemed to utterly lose the ability to make even the simplest decisions.[1] If he tried to decide something as perfunctory as where to have lunch, he would drive to various restaurants, weigh their menus, evaluate seating, and check their wait times, but struggle to choose where to eat. His life crumbled around him. His wife left. He lost his job. He had to move back in with his parents. The more closely linked to things personal or social the decisions were, the harder it became for Elliot to make them.[2] After watching Elliot weigh for 30 minutes the pros and cons of two different appointment times, the researcher working with Elliot said, “It took enormous discipline to listen to all of this without pounding on the table and telling him to stop.”[3]

Based on his work with Elliot and other similar patients, Antonio Damasio was able to isolate the small bundle of nerves in the brain, just behind the eyes, that “integrat[es] visceral emotions into decision-making.”[4] The excision of Elliot’s small tumor damaged this area, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), just enough to remove Elliot’s emotions and his capacity to decide.

It should go without saying that connecting law to fact has been a rational business. We, as lawyers and educators, have made it that way. In neither semester of my torts class were we ever asked by our professor—a good and empathetic man—“Class, have you stopped to think what it must be like to have participated in the crippling of your own child because you yelled at him in order to stop him from drinking from a container of baby oil?”[5] And, if you’ll forgive my hyperbole here, I think it’s a sin if we don’t ask that question in torts, and if we teach our trial advocacy students, or foist on our jurors, a cool and completely rational opening or closing. Who knows? We may be participating, in some small way, in the crippling of their decision-making.

The great trial lawyer, Gerry Spence, says of effective trial lawyering, “To move others, we must first be moved. To persuade others, we must first be credible. To be credible, we must tell the truth and the truth always begins with our feelings.”[6] However, it’s hard to feel sometimes and even harder to adjust to the idea that others, jurors for instance, can or even should be let into our own feelings. There are so many things about law school that condition us against the instinct to share our emotions, don’t you think? Well, may I just say to you, as an encouragement, that I think it’s a terrible idea for you to catch your feelings up in a pillowcase and reach for the nearest rock. I hope none of us ever asks our students or jurors to do it.

[1] Jonah Lehrer, Feeling our way to decision, The Sydney Morning Herald (Feb. 18, 2009), https://www.smh.com.au/national/feeling-our-way-to-decision-20090227-8k8v.html.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] A rough summary of a failure-to-warn case that hasn’t left me in 23 years. Ayers v. Johnson & Johnson Baby Products Co., 147 Wash.2d 747 (1991).

[6] Gerry Spence, Win Your Case 32 (2005).

Brain Lessons: The Seven Percent Delusion

Advice from mock trial judges must be taken with the proverbial grain of salt. Especially from one who, after expressing surprise over a move by students to use the defendant’s deposition in the plaintiff’s case, opined that “you don’t necessarily have to meet your burden during your case.” But I was intrigued, if abashed by my lack of knowledge, when she later told the students “Here is one piece of advice I give all my students – communication is only 7% word choice; the balance is 55% body language and 38% tone.”

Had I missed something? Was there a knowledge base to support this? The competition round ended, and I began to search. It turns out to be myth, just like the “80% of all trials are won or lost in the opening statement,” but tracking it was revealing.

The claim comes from early 1970s research by psychologist Albert Mehrabian. It is prevalent in web searches:

- Communicate Efficiently With Albert Mehrabian’s 7% Communication Model, https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/communicate-efficiently-with-albert-mehrabian-7-communication-model-c88b569a98fe

- Rule of Personal Communication https://harrisonwendland.medium.com/ruleofpersonalcommunication-763a42eedf98

It is discussed in wonderment:

The 7–38–55 rule is something that has been explained over and over and over. Albert Mehrabian’s 7–38–55 Rule of Personal Communication is something that has been shared and examined and taught frequently.

At first, I was quite surprised that it is split up the way that it is. Then, I made an intentional effort to look to recognize it in others and in myself.

Wow.

…

I would like to say that this is just a general rule and there are, of course, times when the words are more than just 7% of communication. But, I would be hesitant, at least from my own experience, to say that the order of importance or value would change in any situation.

Id. It is even depicted in vivid imagery:

Communicate Efficiently, supra. But just 5 minutes of delving revealed this to be myth and deceptive.

Why? Mehrabian was testing a limited issue – when a single word was being used to convey an emotion, was it word choice or delivery that did the better job of conveying the sentiment? And Mehrabian himself cautioned as to its limited utility:

- Inconsistent communications — the relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messages. My findings on this topic have received considerable attention in the literature and in the popular media. “Silent Messages” contains a detailed discussion of my findings on inconsistent messages of feelings and attitudes (and the relative importance of words vs. nonverbal cues) on pages 75 to 80.

Total Liking = 7% Verbal Liking + 38% Vocal Liking + 55% Facial Liking

Please note that this and other equations regarding relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messages were derived from experiments dealing with communications of feelings and attitudes (i.e., like-dislike). Unless a communicator is talking about their feelings or attitudes, these equations are not applicable.

http://www.kaaj.com/psych/smorder.html

A thorough debunking of this myth, or stated more kindly, an explanation of the limited focus and utility of Mehrabian’s research, can be found in the Neurodata Lab article “Experts Say…Is Communication Really Only 7% Verbal? Truth vs. Marketing,” https://medium.com/@neurodatalab/experts-say-is-communication-really-only-7-verbal-truth-vs-marketing-9a8e7428fd0f Here are some of the concerns:

· Mehrabian was testing “the liking of one person to another.” Extrapolating findings in this one context (and, of course, without repeated studies validating this assessment) has no foundation.

· The experiment used photographs, frozen images of facial expression.

Scholarship has also acknowledged the limits of Mehrabian’s findings. See, e.g., Bucklin, More Preaching, Fewer Rules, 35 Ohio N.U.L. Rev 887, 947-948 (2009), emphasizing that

[i]t is emphatically not the case that nonverbal elements convey the bulk of the message regarding moral values. The point is that when the conveyed message is about values, about what is good and what is bad, actions and nonverbal clues are more important than words. The Mehrabian Factor can be simply stated: actions showing values will displace words stating values.

There is even a youtube explanation of the lmits of this rule – Busting the Mehrabian Myth .

What are the take-aways? Certainly, what one says can’t be divorced from how the message is delivered. It may be that the more time spent on how the ideas are delivered will enhance persuasion. This is brought home in a research paper, How The Voice Persuades. Van Zant, A. B., & Berger, J. (2019, June 13). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000193 See also, Stockwell and Schrader, Factors That Persuade Jurors, 27 U. Tol. L. Rev. 99 (Fall, 1995); Epstein, It’s How You Say It https://www2.law.temple.edu/aer/its-how-you-say-it/

And in the world of zoom trials, where the face dominates the screen, it may be that a facial expression will convey more than the words the advocate selects. But there is no validity to the 7% rule; and no reason for anyone to teach this as the standard for persuasive advocacy.

BRAIN LESSONS: CURIOUS CASES OF CONFEDERACY – CONUNDRUMS OF CONSORTING WITH CRIMINALS

by Grant Rost

I have observed a curious phenomenon among wild turkey during the spring breeding season—which is blooming now, right along with the daffodils. Male turkeys (toms) will often travel in packs and they display some pack behavior as they search for a mate. There is, in lupine terms, an “alpha” tom. If a hen is discovered, he will be the one to strut for her and he’ll fight off any competitors. His tagalongs act the part of deferential wingmen. They sit patiently on the sidelines and largely do nothing. However, if that alpha tom is taken by a hunter, the whole event turns into something out of Nat Geo: Ignoring the unbelievably loud and unnatural sound of the shotgun blast, the other toms will rush in to kick, hack, and peck at the helpless victim. These tough facts of nature serve to prove true Tennyson’s observation that “…Nature, [is] red in tooth and claw.”[1] Crows display similar behaviors and will dive upon, and even eat, a flock member who shows weakness or is in the throes of death. There is a rumor that this behavior is why a flock of crows is called a “murder.” These toms and crows, once “in-group” confederates of feather and flock, seem to have made an “out-group” of their fallen comrades.

Though not a perfect analog, these avian facts are, admittedly, what sprang to mind when I read the study I’ll review this month. It’s a study on out-group and in-group bias.[2] As you might know or glean from context, out-group bias is the phenomenon of those ugly biases we feel towards those who we don’t consider to be like us or part of “our” group. In-group bias is the favorable bias we extend to those who we think are like us or who are in our group. This particular study in these biases sought to determine how jurors would treat defendants and victims who had one or more brothers who were convicted criminals.[3] If a defendant had, say, three brothers who were criminals, would a jury be more likely to convict? If a victim had three brothers who were criminals, would jurors be more inclined to acquit? As you can imagine, the findings of the study would seem to hinge on how much a juror identified with the defendant or victim—making them part of the in-group—or how much they considered the defendants or victims to be “in” or “out” with their nefarious brothers.

The methods of the study are rather detailed, so for the sake of my limited available space here I will boil it down in a way that will, admittedly, oversimplify it. There were two studies here. One study gauged how mock jurors handled evidence that a male defendant with no criminal record had zero, one, or three brothers with criminal convictions. The second study measured how mock jurors handled evidence that a male victim of a crime had zero, one, or three brothers with criminal convictions. The fact pattern for the case involved an assault and battery, so there was a prospect that the defendant could have been acting in self-defense against the more-aggressive victim. After reading the fact patterns, mock jurors were asked a battery of questions to gauge their degree of identification and affiliation with the defendant and victim. Researchers asked the mock jurors numerous questions about blameworthiness, deservedness (that is, did the defendant or victim deserve what happened to them), the likelihood of self-defense, and, naturally, whether the defendant should be adjudged guilty or not guilty.[4]

Let’s now turn to the findings. Unsurprisingly, the more a mock juror identified with the defendant, the less likely they were to convict.[5] If a mock juror identified more with the defendant, they were also more likely to blame the victim.[6] Along these same associational lines, if a mock juror identified more with a victim, they were more likely to convict.[7] If mock jurors thought the victim more similar to his criminal brothers, they were more likely to say that defendant had acted in self-defense.[8] So far, the study seems to reveal neat and tidy in-group and out-group biases.

But then things stop being neat or tidy. Say the researchers, “Contrary to our hypothesis, a greater number of criminal associations caused the defendant to be perceived as less like his brothers [statistical figures omitted], not more.”[9] To put it another way, if a defendant had three brothers convicted of crimes, his own clean record caused mock jurors to believe he must be the good egg of the family. Additionally, the more criminal associates a defendant had the more likely jurors were to believe the defendant had acted in self-defense.[10] Finally, say the authors:

For defendants, having criminal associates was mostly advantageous; and when it was not advantageous, the effects were null rather than disadvantageous. Victims received the opposite treatment. Mock jurors perceived the victim more negatively when he had criminal associates compared to no criminal associates, and in these instances the defendant received relatively favorable perceptions.[11] [Emphasis added.]

You have to now admit that I had you confused in the beginning, didn’t I? You had a moment up there where you were sure I’d lost it with my turkeys, and crows, and Tennyson. Perhaps, now, you can see how a study which reveals the uphill battles victims can often face might make me think of creatures that descend mercilessly on their stricken or injured comrades. These clinical revelations are, perhaps, among the chief reasons we study these lurking biases and heuristic short-cuts our brains impose on us: that we may catch ourselves before we kick, hack, and peck at the out-groups we have created around us.

——————————–

[1] Quoted from the poem “In Memorium A.H.H.” Additionally, April is National Poetry Month. Let’s all take a moment or two this month to read some good poetry. I’m happy to offer recommendations on request.

[2] For more information on out-group and in-group biases, see generally J.W. Howard & M. Rothbart, Social Categorization and Memory for In-group and Out-group Behavior, 38 Journal of Personality and Soc. Psyc., 301-310, 2 (1980).

[3] Peter O. Rerick et al., Guilt by Association: Mock Jurors’ Perceptions of Defendants and Victims with Criminal Family Members, 27 Psych., Crime & L., 282 (2021).

[4] See generally Id. I am, here, editing and oversimplifying the extensive battery of questions posed to the mock jurors.

[5] Id. at 291.

[6] Id.

[7] Id. at 296.

[8] Id.

[9] Id. at 290.

[10] Id. at 291.

[11] Id. at 299.

Brain Lessons: “Tappers” and the Curse of Knowledge

Why don’t those darned jurors hear what I am telling them? Or, asked differently, what did that lawyer mean by giving such an incoherent opening statement – didn’t they realize that details were missing? The answer is that the opening statement may been ‘internally coherent but externally incoherent.’ And how this can occur is best understood by learning about the “tappers” research

That phrase – internally coherent but externally incoherent – is one this author generated after reading an opening statement from a Pennsylvania criminal trial. There was a hint of a story, but new names and seemingly disconnected events were thrust at the jury in a way that no one who had yet to read the discovery could grasp.

How could the presenter be so unaware of the failure to communicate? The answer comes from the 1990 “tappers” study. A Stanford University graduate student, Elizabeth Newton, asked study participants to think of a well-known song and tap out the rhythm to that song on a table-top. For each tapper, a separate participant had to listen to the taps and ‘name that tune.’ [Try this – take the song “Happy Birthday” and tap out its rhythm as you sing it to yourself.]

Not surprisingly, out of 120 tapped songs, only three were correctly identified. But Newton focused on the tappers’ expectations – and they predicted a 50% success rate for their listeners. What was the take-away? The tappers had the knowledge of the song in their heads, ‘heard’ it as they tapped, and attributed that knowledge to their listeners.

That type of cognitive processing and its consequences have been labeled “the curse of knowledge.” It afflicts legal writing (and writing in other contexts – see The Source of Bad Writing; The ‘curse of knowledge’ leads writers to assume their readers know everything they know, Pinker, Steven . Wall Street Journal (Online); New York, N.Y. [New York, N.Y]25 Sep 2014)). It even impedes medical diagnosis and treatment. J. Howard, The Curse of Knowledge, Chapter 9 in COGNITIVE ERRORS AND DIAGNOSTIC MISTAKES (Springer 2019). And research continues to affirm the phenomenon. Damen et al., Can the curse of knowing be lifted? The influence of explicit perspective-focus instructions on readers’ perspective-taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol 46(8), Aug, 2020. pp. 1407-1423. Ultimately, it is core to modern persuasion theory across all domains, a point driven home by Chip and Dan Heath in MADE TO STICK (Random House 2007).

Little has been written about this specific to courtroom advocacy. One article identifies how this works [or causes failure] at trial:

By the time a case reaches a jury, the trial team is waist-deep in depositions, evidence, and briefs, which have been collected over a course of months or even years. The attorneys have thought through a plethora of conceivable issues that could arise at trial and have formulated responses. The case is engrained in their minds and, consequently, they can overestimate the ease with which jurors will understand their case. Attorneys have the benefit and the limitation of knowing too much about the case and the law, often resulting in too many layers of assumptions and presumptions about the messages sent to jurors.

O’Toole, Boyd and Prosise, THE ANATOMY OF A MEDICAL MALPRACTICE VERDICT, 70 Mont. L. Rev. 57, 61 (Winter 2009). The authors diagnose this as having a presenter who is sender-based rather than audience-based. Id., 60.

Can the curse of knowledge be overcome? The first (necessary but not sufficient) step is to remember that what is needed is a “concrete” story. Beyond that, however, the research by Damen offers little hope in terms of going it alone – trying to make oneself ‘hear’ as the uninitiated would is a difficult task, although one advocate has urged a weekend of forgetting about the case and then returning to it anew, which he promises offers a fresh understanding of what jurors might need to know. Perdue, SYMPOSIUM: THE “BEST OF” LITIGATION UPDATE 2017: PERSUADING THE NEXT GEN JURY (OR ANY GEN FOR THAT MATTER), 79 The Advocate 203, 209 (2017). [In a subsequent article, Perdue suggests that lawyers also reimagine their case after jury selection has occurred, as knowledge of juror backgrounds and interests can inform how best to present the information. Perdue, SYMPOSIUM: EFFECTIVE TRIAL ADVOCACY: PRESENTING EVIDENCE WITH AN EYE TOWARD YOUR JURY, 90 The Advocate 44 (Spring 2020).]

But there are remedies once the presenter is aware of the risk – and the simplest/best is to find a test audience. Give the opening to an audience with no familiarity with the case, and then test whether the story landed by asking for it to be told back to you – or pepper the audience with questions that can be answered only if ‘your’ story became theirs.

The same is true in appellate advocacy. Share the statement of facts with someone and then see if that reader can make sense of your legal arguments or needs more information.

Until lawyers become audience-based and aware of their ‘tapper’ proclivities we will have presentations that are externally incoherent. [For a quick “tapper” tutorial for your advocacy students, show them the youtube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPAryjQs-Pw

Brain Lessons: How We Make an Appearance

by Grant Rost

With Valentine’s Day less than a week away, I am again trying to become a better, more romantic version of myself. It is the season for it. It started me thinking about poetry and, specifically, Shakespearean sonnets and the works of Lord Byron. The most famous poems from the two authors both start with the beauty of their respective muses. Shakespeare asks, “shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate…”[1] Byron, perhaps finding the beauty of a summer’s day too small, likens the beauty of his love to the whole doggone universe. He says, “She walks in beauty, like the night / Of cloudless climes and starry skies, / And all that’s best of dark and bright /Meet in her aspect and her eyes; / Thus mellowed to that tender light / Which heaven to gaudy day denies.”[2] So long as attractiveness has existed, we’ve been enamored with it—written poems and songs about it. It should come as little surprise then just how obsessed our brains are with human appearances in general and beauty in particular. But, oh! It doth ensnare. The silk we find in skin. The call of raven hair! Unfortunately, there is very little that is romantic or poetic about how the unconscious brain processes human

appearance.

With a more objective eye, I wanted to take another look this month at our old friend the “halo effect.” As part of our blog series, I’ve written about the halo effect before; in particular, how mock jurors placed inordinate amounts of trust in drug-sniffing dogs and the effects of

attractiveness on sentencing. As a refresher, the halo effect is a cognitive short-cut in which a particular characteristic—usually a positive trait, but not always—is irrelevantly extended to other judgments one makes about the person “wearing” the halo. This time around, my purpose is a

little different. While I will touch on some research about how human beings process physical appearance, I wish this month to pose some larger questions on which to meditate.

Let me begin with a confession. Shortly before I was to represent a criminal defendant accused of imposing himself on one of his employees, I made him cut his hair. To be precise, I made him cut off the tail of his mullet. You see, that longer tail of hair, when coupled with his curly salt-and-pepper locks, made him look a little too much like Joey Buttafuoco. For our younger readers, you may have to Google that one. At the time of the trial, however, I didn’t want to risk any association with the notorious philanderer. We have all done this, haven’t we? We have all

altered the appearance of at least one of our clients before trial. The prosecutor in the above case was apparently reading from the same script. My client’s accuser appeared in court dressed in white and only two of the more than dozen piercings she had in her nose, eyebrows, lips, and ears

remained. At that point, I had not read any research on how appearance affects opinions, judgments, and verdicts. I wonder now whether the prosecutor was studied up on the subject. It is worth noting here just a few findings from this vast body of research.

One study found that people generally hold to a set of stereotypical physical traits which they believe attach to criminals: tall, thin, male, dark hair, dark clothes, and beady eyes.[3] In

another, participants sorting faces based upon a hypothetical “more-criminal” or “less-criminal” measure were surprisingly in sync with their estimations on what criminals and non-criminals look like.[4] In a different study, participants assigning sentences to white defendants

punished them more severely than black defendants for white-collar crimes and punished black defendants more severely than white defendants for violent crimes.[5] In a non-legal but related study, voters were found to infer the personality traits of a candidate based on the

candidate’s physical appearance and the *inferred* traits actually influenced later voting decisions.[6]

As a teacher of advocates, I am constantly stressing to my students how important authenticity is. I tell them not to try to create a courtroom persona that is different from the person they are outside of the courtroom. I encourage them to banish from their voice boxes the sounds of

the Telepromptered speechmaker and the cajoling lilt of the car salesman. Yet in what seems a stunning bit of hypocrisy on my part, I’ve essentially said to my clients whom I asked to change, “The real, authentic me! But not for thee!” I’m not the least bit kidding when I say I still feel torn

about these choices. There is, naturally, the larger part of me that believes I *should* try to overcome whatever irrelevancy jurors will irrelevantly and prejudicially use against my client because of their own unconscious biases. And it is from this internal rift that springs the

real questions that I wish to pose, rhetorically, in this blog: what should we teach our students about this sort of client “prep” and how do we prepare our students for the unconscious minds of their clients’ jurors? What, if anything, is the limiting principle we teach our students on

whether they alter their client’s appearance or not?

In Sonnet 148, Shakespeare elegantly poses questions about whether his eyes see what is true about another or if his judgment “censures falsely what [my eyes] see aright?”[7] To the extent he landed on unconscious bias in the late 1500’s, he must be the sage we often find him to be. If it is proper or traditional to makes wishes on Valentine’s Day, and I hope it is, then I have this one to share with you: My wish, dear friends and readers, is that we may get to gather in person

again soon to discuss these questions and the host of the others we think upon as teachers and zealous advocates.

——————————

[1] William Shakespeare, Sonnet 18, in William Shakespeare: Complete Poems 133 (1993).

[2] Lord George Byron, She Walks in Beauty, in The Book of Living Verse 251 (Louis Untermeyer ed., 1945).

[3] See generally, D. J. Devine & D. E. Caughlin, Do They Matter? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Individual Characteristics and Guilt Judgments, 20 Psych. Pub. Pol’y & L. 109 (2014).

[4] See generally, Alvin G. Goldstein et al., Facial Stereotypes of Good Guys and Bad Guys: A Replication and Extension, 22 Bull. Psychonomic Soc’y 549 (1984).

[5] See generally, Randall A. Gordon et al., Perceptions of Blue-Collar and White-Collar Crime: The Effect of Defendant Race on Simulated Juror Decisions, 128 J. Soc. Psych. 191 (1988).

[6] See generally, Christopher Y. Olivola & Alexander Todorov, Elected in 100 milliseconds: Appearance-Based Trait Inferences and Voting, 34 J. Nonverbal Behav. 83 (2010).

[7] William Shakespeare, Sonnet 148, in William Shakespeare: Complete Poems 198 (1993).

Brain Lessons: Who/What To Trust – Science or Experience?

It is beyond question that we inhabit a nation where, to some, a trusted voice is more valued than hard data and science. Why? Are some people hard wired (or might we say “politically wired”) to view scientific evidence either as credible or untrustworthy? And if the answer is “yes,” what does that imply for courtroom advocacy – in the jury selection process or at trial itself? Or for how we teach trial skills to our students?

This is the problem analyzed in the paper “We Should Hear from Both Sides: Ideological Differences Between Liberal and Conservative Attitudes Toward Scientific and Experiential Evidence,” by Stein, Swan and Sarraf (2019) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3428776, last visited November 7, 2020. The overarching research question asks if someone’s political leanings are predictive of whether the individual will credit the ‘researcher’ or the ‘rejecter.’

To test this, they used problems not usually connected to public policy and politics, such as whether people accept the science of global warming. Consider this example: “a researcher debunks the possibility of ‘lucky streaks’ in games of chance, while a casino manager says he does not believe the researcher and claims to have seen lucky streaks.” To really measure how dominant political allegiance might be, the authors even added information that would help the test subjects understand why the casino manager might be wrong.

The outcome of the initial research was stark in its findings:

- “compared to liberals, conservatives evaluate the science rejecter more favorably…[and] conservatives also evaluated the researcher less favorably than liberals…” Id, 14-15

- “Looking at liberals and conservatives only, among those who preferred the researcher, 37.0% are conservative, while among those who preferred the rejecter, 77.4% are conservative, and among those who gave equal ratings to both, 59.3% are conservative. Thus, those who do not rate the researcher more positively than the rejecter are especially likely to be conservatives…” Id., 15

The first of two studies found that conservatives treat “scientific and non-scientific perspectives as closer in legitimacy to one another” with one reason being that they see “intuitions as an infallible source of truth.” Id., 17.

This does not mean that science did not prevail. After a second study, the researchers concluded that “both conservatives and liberals, on average, evaluated the researcher more positively than the rejecter, indicating that both groups overall see the value in science and, at least on these [non-politically-charged] issues, tend to think the scientific perspective is more likely to be the correct one.” Id., 21.

Was there a bottom line? One conclusion was that conservatives hold sincere beliefs that what people experience is as legitimate a source of truth as scientific evidence. As well, “the case that intuitive thinking makes empirical understanding difficult continues to be clear.”

Okay, an interesting digression into mainstream thinking. But what might this have to do with trial advocacy? Plenty. Just some of the considerations this research triggers include the following:

- What is fair jury voir dire in a data-driven case where the jurors may also hear experience-based testimony that counters the research. It is doubtful that judges would (or should) permit the question “what are your political leanings,” but might it be appropriate to ask “if you heard a mathematician say that ‘odds always favor the casino’ but a blackjack dealer testifies that ‘lots of people beat the system’ would you tend to believe one or the other?”

- What expert do you select, and how do you ‘school’ that person to make data seem more tangible and trustworthy?

- Can you find a story to make the jurors who are more conservative “think slowly” and get to the place where they can reason past their intuitive thinking?

There is one more consideration, and that is for those who teach advocacy skills to law students and to young lawyers: when do we introduce them to studies like these and explain that our model direct- and cross-examinations are just that – generic models for the ‘reasonable person’ juror in a world where that stereotype may have less and less relevance?

BRAIN LESSONS: IT’S HOW ONE SAYS IT

Tremendous time and effort are spent on word choice – drafting the perfect motion in limine, opening statement, and/or closing argument. However, it may be that the more time spent on how the ideas are delivered will enhance persuasion more than the words used.

This is brought home in a new research paper, How The Voice Persuades. Van Zant, A. B., & Berger, J. (2019, June 13). How the Voice Persuades. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000193

The focus here is on “paralanguage,” defined as the use of the voice – sound, pitch, volume, speed of delivery – and nonverbal communication such as gesture, pausing, and movement.

The importance of paralanguage has not escaped judicial attention. One case explained that an appellate court must defer to a jury’s interpretation of

an audio-recorded statement as opposed to a written transcript. Spoken language contains more communicative information than the mere words because spoken language contains “paralanguage“—that is, the “vocal signs perceptible to the human ear that are not actual words.” Keith A. Gorgos, Lost in Transcription: Why the Video Record Is Actually Verbatim, 57 Buff. L. Rev. 1057, 1107 (2009). Paralanguage includes “quality of voice (shrill, smooth, shaky, gravely, whiny, giggling), variations in pitch, intonation, stress, emphasis, breathiness, volume, extent (how drawn out or clipped speech is), hesitations or silent pauses, filled pauses or speech fillers (e.g., ‘um/uhm,’ ‘hmm,’ ‘er’), the rate of speech, and extra-speech sounds such as hissing, shushing, whistling, and imitations sounds.” Gorgos, supra at 1108. The information expressed through paralanguage is rarely included in the transcript, as there is generally no written counterpart for these features of speech. Gorgos, supra at 1109.

People v. Hadden, 2015 IL App (4th) 140226, P28, 44 N.E.3d 681, 685-686, 2015 Ill. App. LEXIS 953, *10-11, 398 Ill. Dec. 652, 656-657.

How The Voice Persuades put paralanguage to the test, seeing whether how a message was delivered impacts listener receptivity, in particular whether the audience will believe the presenter’s contention.

A series of experiments was conducted where the effect of paralanguage was assessed. Important to the researchers were two phenomena – detectability and confidence. “Detectability” addresses whether the listener can detect a goal of being manipulated, one that is often found in word selection but less manifestly in how words are delivered. “Confidence” is the speaker conveying “attitude certainty,” i.e., a strong subjective belief in the expressed belief(s).

In one experiment, speakers either did or did not disclose that they had been paid to review the item (a tv) they were promoting. While disclosure of course allows detectability, the impact of paralanguage- varying the presentation in its delivery – increased receptivity of the message even when the speaker’s intent was disclosed. As the study reports, “even when presented with information known to increase the salience of communicators’ persuasive intentions, participants did not become more likely to resist paralinguistic attempts.” Plain English – even when listeners were told that the speaker was paid to review the item, paralanguage made more people receptive to the message that this was a good tv to purchase. One conclusion was that speaker confidence overrode the distrust of knowing the presenter has an agenda.

And which paralanguage cues were most effective? Again, the report details the findings:

Speakers were more persuasive when they spoke at a higher volume (z _ 2.64, p _ .008) and when they varied their volume (z _ 2.14, p _ .033). Notably, these two cues were both displayed by speakers when engaging in paralinguistic persuasion attempts. Though speakers increased their pitch, pitch variability, and speech rate during paralinguistic attempts, these cues did not impact attitudes…

[S]peakers’ paralinguistic persuasion strategy of increasing their volume and varying their volume made them appear more confident, which in turn made them more persuasive.

What is the upshot? The authors acknowledge the need for further research, and urge that more be done to assess whether additional variables – in particular “increased pitch, increased speech rate and fewer pauses” will also impact acceptance. And in domains where accurate judgments are paramount[,]” it will be “faster speech rate, fewer pauses and falling intonation” that may enhance listener acceptance.

For now, the lesson is simply – just as we were once taught that “the medium is the message,” it is sound as well as content that may be core to persuasion.

BRAIN LESSONS: ATTRACTIVE ROTTEN SCOUNDRELS

by Grant Rost

I [Grant] discovered recently that Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, the hilarious movie about two con-men competing to swindle a rich heiress, was released on December 14th, 31 years ago. You may recall the premise of the movie: A dashing and debonair swindler, played by Michael Caine, gets into a winner-takes-all swindling battle for an heiress’s money with a low-level con-man, played by Steve Martin. [Spoilers ahead! Skip to the next paragraph and then proceed to Netflix.] In a terminating twist, the lovely heiress, played by Glenne Headly, swindles them both. Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (MGM Studios 1988).

The movie’s con-men, played by physically attractive Hollywood stars, are an exemplary backdrop to answer this month’s cognitive question: Does the attractiveness or unattractiveness of a swindler affect how a police officer would choose to blame and punish them? For instance, would a male or female police officer treat, say, an attractive male swindler the same way they would treat an unattractive male swindler? These interesting questions, and more, were tested by researchers Mally Shechory-Bitton and Lisa Zvi in a study published last year. Mally Shechory-Bitton & Lisa Zvi, Chivalry and Attractiveness Bias in Police Officer Forensic Judgments in Israel, 159 The Journal of Social Psychology, no. 5, 2018, at 503, https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1509043

Lawyers likely have varying views of how an accused’s physical attractiveness may impact his or her case. The idea that one’s attractiveness or unattractiveness can affect other’s judgments about them is part of a well-known cognitive bias called the “halo effect.” As a refresher, the halo effect is a cognitive short-cut in which a particular characteristic—usual a positive trait—is irrelevantly extended to other judgments one might make about the person “wearing” the halo. Thus, it seems most lawyers believe that the glowing halo of an attractive defendant might extend to a judgment of lower culpability or a reduced sentence. Indeed, the authors of this study cite multiple studies bearing out the truth that the most-attractive criminals among us might benefit from their looks in ways the system never intended. See generally, Id.

For this experiment, the authors crafted a story vignette in which the swindle was the same but the authors could swap in-and-out attractive and unattractive swindlers and attractive and unattractive marks. Id. at 506. The vignettes were accompanied by photos of men and women who would serve as the fictitious swindlers and marks. Each male and female photo had been thoroughly tested through survey groups to objectively categorize each swindler and mark as attractive or unattractive. Id. at 506, 507. The vignettes were given to a few hundred male and female police officers and a few hundred male and female college students who served as a control group. Each respondent was asked to assign a level of culpability to the swindler and the mark, and then asked to assign a particular sentence to each swindler on a spectrum of high-culpability imprisonment to low-culpability therapy or rehabilitation. Id. at 507.

The prevailing wisdom of the halo effect, as it relates to the more pulchritudinous among us, is that they benefit from their good looks without much hindrance. However, the study revealed quite the opposite when it came to the more dashing and lovely swindlers. Say the authors, “In contrast to the attractiveness bias (citations omitted) the advantage of good looks, which serves good looking offenders well in other types of offences, disappears and might be unhelpful when appearance is used as part of a crime.” Id. at 513 (emphasis added). The squeezing choke of the attractiveness halo appears to be that looks are a criminal asset only when they are not also used as a tool for evil! None of which bodes well, it seems, for our dirty, rotten scoundrels.

BRAIN LESSONS: A DOG IS A JUROR’S BEST FRIEND

by Grant Rost

In honor of national Adopt-A-Dog and Adopt-a-Shelter-Dog month, we will look at an interesting study on drug-dog evidence and mock-juror decision making, examining whether jurors would credit the alert of a drug-sniffing dog as a *sufficient condition* for guilt in a trafficking case. The researchers in this study tested how much credit mock jurors would give to the alert of a drug-sniffing dog in a drug-trafficking case where no drugs were ever discovered and the only evidence of their presence was testimony that a drug-sniffing dog had alerted on the defendant’s automobile. Lisa Lit et al., *Perceived infallibility of detection dog

evidence: implications for juror decision-making* (2019), *available at*

https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2018.1561450. For just a word on the legal backdrop of this kind of evidence, the United States Supreme Court has approved of the admissibility of drug-dog alerts—though admissibility of that evidence is not without qualification. *Florida v. Harris* 568

U.S. 237 (2013).

The researchers provided the subjects with a summary of testimony showing that a drug-sniffing dog alerted on the defendant’s car, though no drugs were ever found. The dog’s alert was used to gain a warrant for defendant’s house where police found only a large sum of

stashed money. Subjects were asked, among a host of other questions, whether the defendant was guilty of drug trafficking, how confident they were in their verdict, and how confident they were that a drug-dog alert indicated the presence of drugs. Lit, et al, *supra *at 194.

Though a majority of the mock-jurors issued a not guilty verdict, 33.5% of the 554 participants voted to convict the defendant for drug trafficking even though no drugs were ever found in the defendant’s car or house. *Id. *Furthermore, “Participants assigning a guilty verdict

were more likely to indicate high levels of confidence in their verdict (70% or higher) than those assigning a verdict of not guilty [statistics omitted].” *Id. *at 197. 80% of all participants either agreed or strongly agreed that a drug-dog’s alert at a location where no drugs were found simply meant that drugs were present at some point, even though such alerts could result from dog or handler errors. *Id. *at 195, 197. If the reader has pondered the so-called “halo effect” before—the human tendency to like or dislike, credit or discredit a person based on who they are or

how they are perceived—it is likely you have never considered any powers a dog’s halo might have.

You may or may not know that the origin of the famous phrase “a dog is a man’s best friend” is traced back to a rather rousing closing argument offered up by George Vest in a small Missouri courtroom in 1870. Vest’s soaring oratory on the plaintiff’s deceased dog is worth a trial

lawyer’s read. Though Vest says that dogs are faithful, unselfish, and noble, we humans appear willing to also credit them with honesty, accuracy, and forensic reliability.

BRAIN LESSONS: THE POWER OF STORY-TELLING

After 300+ exonerations, and the attraction to forensics engendered by television series, one might think that the recovery of DNA at a crime scene – DNA that does *not* match the defendant – would quickly lead to acquittal. The contrary has occurred, however, particularly where a ‘good story’ to ‘explain’ the foreign DNA is told.

In NOTE: THE “ELASTICITY” OF DNA EVIDENCE? WHEN PROSECUTORIAL STORYTELLING GOES TOO FAR, 28 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Social Justice 138 (April, 2019), the following is reported:

In the recent psychological study, When Self-Report Trumps Science: Effects

of Confessions, DNA, and Prosecutorial Theories on Perceptions of Guilt,

Sara C. Appleby and Saul M. Kassin analyzed people’s perceptions of guilt

when presented with the following: a defendant who had confessed to a

crime, DNA evidence exculpating that defendant, and a prosecutor’s theory

explaining the contradictory evidence. Although the study confirms that

people are more persuaded by DNA than by confessions, participants in the

study were three times more likely to convict when a prosecutor offered an

explanation of why the exculpatory DNA conflicted with the confession than

when no explanation was presented.

*Id.*, 139-140.

The NOTE goes on to show that this occurs not just in the psychology lab but in the courtroom.

The Center on Wrongful Convictions has reported 19 known cases in which a

defendant confessed and was convicted despite exculpatory DNA, with

additional cases having been reported since then. In rape-murder cases, a

common prosecutorial theory used to override exculpatory DNA in the form of

semen is known pejoratively as “the unindicted co-ejaculator” theory. The

story advanced by prosecutors in these cases is that the victim had prior

consensual sex with an unknown male; afterward, the defendant raped her,

failed to ejaculate, and killed her. Prosecutors have also argued

necrophilia, conspiracy, and other questionable theories in order to

discount exculpatory DNA.

*Id.,* 148.

The proof of the potency of story-telling is in the guilty verdicts – the story triumphed over the science.