Teaching Outside the Book

by Trish Wieland

There are people who help others not by just doing for them, but listening to them, researching root problems and helping them create better, stronger communities despite societal obstacles. It’s a growing trend on college campuses known as civic engagement and community-based research and learning. It usually starts with a professor and, like a candle, lights the way for students to follow, fortify and improve communities.

“These programs model the idea that giving something back to the community is an important college outcome,” said George D. Kuh in his book, High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter, “and that working with community partners is good preparation for citizenship, work, and life.” Kuh, nationally renowned for his research and writing regarding student engagement, assessment and institutional improvement, is the director of the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Civic engagement and community-based learning is about immersing oneself into the community to understand and resolve problems as well as increase the quality of life for everyone.

“Professors engaging their students with the community as a way of teaching course content can be energizing and refreshing,” said Michael Norris, director of Member Services for Florida Campus Compact, “and the research tells us that faculty members find this to be true.” Norris’ organization is a state affiliate of Campus Contact, a national higher education association.

Case-in-Point

For programs that involve students in their communities, “field-based experiential learning with community partners is an instructional strategy and often a required part of the course,” said Kuh. “The idea is to give students direct experience with issues they are studying in the curriculum and with ongoing efforts to analyze and solve problems in the community. A key element in these programs is the opportunity students have to both apply what they are learning in real-world settings and reflect in a classroom setting on their service experiences.”

A specific case study from Stetson University is Florencia Abelenda. While a junior at Stetson, Abelenda (pictured in the main photo above) stood up to an entire city council because her months of research and interviews with agricultural workers in Pierson, Fla., showed a desperate need for their children to have a safe and positive after-school activity.

Abelenda was kicked out of that meeting but she kept advocating for those children and for the underserved farm workers of the community because her thorough and thoughtful research and surveys pointed out that there were clear problems in the community that needed to be addressed.

What were the problems? High levels of gang/drug activity, school dropouts, teen pregnancies, and racial and social-economic segregation in the town. Abelenda’s four months of research also showed that an overwhelming 90 percent of the student population wanted an after school program, with nearly two-thirds of them acknowledging that they would be able to get better grades with more tutorial support.

“Florencia’s efforts had a significant positive impact on the entire community because she was the voice for a large, underserved portion of their population,” said Abelenda’s community-based research professor, John Schorr, Ph.D., who retired from Stetson last year after 30 years as a professor of sociology.

“Florencia didn’t take ‘no’ for an answer and overcame the obstacles for the greater good,” explained Schorr. Going above and beyond the research component, Abelenda, with a lot of help from her classmates, launched a successful 4-H program in Pierson her senior year.

Since graduating in 2010, Abelenda has been a part of several organizations known for their community outreach such as Save the Children, The Institute for Social and Economic Development and Google.

Professors Light a Spark

“Civic engagement and community-based research is different than volunteering in the traditional sense,” Schorr explained. “It is part of a much deeper process and immersion, more lasting and responsive to what the community says about its own needs.”

For his unyielding commitment to civic engagement and community-based research, Schorr was recently selected as a finalist for the AAC&U/Campus Compact Thomas Ehrlich Civically Engaged Faculty Award and, with that, he was a panelist at the 2015 AAC&U annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

“I have worked with numerous talented, visionary community impact leaders throughout my career in higher education and community engagement,” said Savannah-Jane Griffin, director of Community Engagement at Stetson, who recommended Schorr for the award. “Without a doubt, John is one of the very best.”

Schorr and his students have made sustainable and substantial improvements with non-profit agencies in DeLand and Volusia County by addressing systemic issues including poverty and homelessness, emergency management and preparedness, health care, public housing needs and farmworker health needs.

Professors across the country are embracing the educational philosophy and benefits of embedding civic-engagement and community-based research into their curriculum.

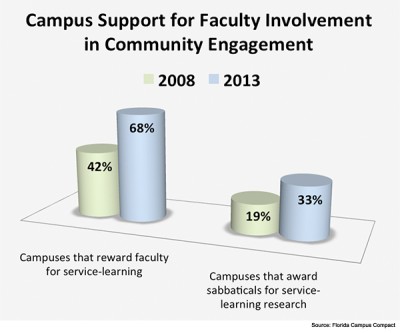

“Faculty involvement is important for creating a culture of engagement on campus and for connecting community and academic work in ways that enhance student learning,” said Norris. “Community engagement as a pedagogy has become well established. Sixty-eight percent of campuses reward faculty for service-learning and community-based research, up from just 42 percent in 2008. Sabbaticals for service-learning research, scholarship, and program development have become much more prevalent, offered by 33 percent of member campuses in 2013, up from 19 percent in 2008.”

“Faculty involvement is important for creating a culture of engagement on campus and for connecting community and academic work in ways that enhance student learning,” said Norris. “Community engagement as a pedagogy has become well established. Sixty-eight percent of campuses reward faculty for service-learning and community-based research, up from just 42 percent in 2008. Sabbaticals for service-learning research, scholarship, and program development have become much more prevalent, offered by 33 percent of member campuses in 2013, up from 19 percent in 2008.”

Students in the classes taught by Ranjini Thaver, Ph.D., professor of economics at Stetson, shared their time and passion teaching business and emotional intelligence in a local correctional institution as well as in economically challenged sections of DeLand.

Thaver has worked to improve lives across the world as well. Having started the microcredit program at Stetson in 2001 after a trip to Tanzania, Thaver applied the microcredit principles to help men and women there who had little to no established credit, but were rich in human capital, to receive microloans and turn themselves into successful business owners.

“I never feel the need to inspire my students directly,” Thaver said. “They act from their hearts and minds to work with a community to make improvements.”

Implementing Principles

Stetson Provost Elizabeth “Beth” Paul, Ph.D., believes that having faculty who engage with the community and promote the university-wide value of serving others both on and off campus are the keys to successful integration of this type of learning.

“Daring to make a positive contribution to all communities makes for a powerful learning environment,” Paul said. “Faculty who are engaged serve as a model of how to act and how to make a positive difference. All sorts of learning are important, but community-engaged learning is especially important.”

According to Norris, Stetson has held the Carnegie Classification for Community Engagement since 2008. This elective classification identifies institutions that are doing excellent work. There are only 361 campuses nationwide that have the Community Engagement Classification, and Stetson is one of only 14 in Florida.

“It’s easier at institutions that, like Stetson, have a Center for Engagement to assist faculty with making connections to community partners, and details such as transportation, insurance, risk management, and memorandums of understanding between the college and community partner organizations,” noted Norris.

Schorr believes Stetson’s success with community-based learning played a significant role in the establishment of a Bonner Scholars Program in 2005. That program awards substantial scholarships to community-engaged students and is a catalyst for student-led community transformation and social justice.

Bonner students work with partners in their communities, to collectively and collaboratively solve problems through service internships. A Bonner recipient serves 280 hours per school year for four years, as well as 280 hours for at least two summers of service.

“Their time is spent roughly 80 percent on service and 20 percent on training and enrichment,” said Robert Hackett, president of the Corella and Bertram F. Bonner Foundation. According to Hackett, the program helps support 3,000 students each year at more than 65 colleges and universities nationwide.

Hackett further explained that because the challenges facing our communities are complex and interwoven, solving them requires interdisciplinary thinking, knowledge of policy and politics, and the skills and motivation to engage with a diverse range of individuals and institutions working together to bring about change.

“While Bonner Scholars and other students are gaining invaluable first-hand experiences in addressing these needs, they need deeper education and broader perspective that only our most engaged faculty and our community partners as co-educators can offer them,” said Hackett.