Volunteering in N’Awlins: Po-Boys, Dubstep, Helping Others

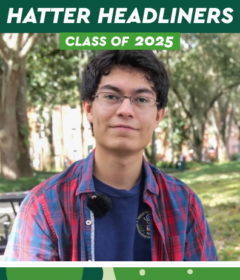

During Stetson’s recent spring break, 12 members of the Stetson community traveled to Louisiana to work with a local nonprofit organization in New Orleans. The organization helps to rebuild homes of Hurricane Katrina victims. I am Philip Yang. I am a junior accounting major and am happy to present the following as my personal account of the experience.

This being my fourth alternative spring break trip at Stetson, I felt especially confident about this trip to “N’Awlins” and quickly jumped into conversations with three of my colleagues about why they came on this trip. A tall graduate assistant named Anderson nodded confidently, affirming the sentiments spoken by others. Veronica, a member of Stetson’s staff, said she wanted to give New Orleans the help it needed. Another staff member named Barbara told me that she wanted to help people, learn about herself and experience the city.

This being my fourth alternative spring break trip at Stetson, I felt especially confident about this trip to “N’Awlins” and quickly jumped into conversations with three of my colleagues about why they came on this trip. A tall graduate assistant named Anderson nodded confidently, affirming the sentiments spoken by others. Veronica, a member of Stetson’s staff, said she wanted to give New Orleans the help it needed. Another staff member named Barbara told me that she wanted to help people, learn about herself and experience the city.

Together, these folks and I made up the 2015 Alternative Spring Break trip from Stetson University to New Orleans. After asking the eight other students and the three faculty members about their reasons for coming on the trip, I was surprised to find out that some of them had no prior experience volunteering during their vacation; some had experience from a prior college volunteer trip; and others had done volunteer work on a church trip in the past.

We stayed at a location called The Village and worked for the organization Project Homecoming, “Committed to Building Faith,” as their website states.

As I awakened each of the five days, I would rise early and quickly from a firm bed in a dorm-like room. We all took turns making breakfast for the group. In my opinion, New Orleans, as a personality, was a hardened city. The city seemed mixed with affluence, manufacturing, hurricane damage, poverty, tourism and a surprisingly bold, rough aura. Unashamed, commercial lots were empty, abandoned, or half-occupied on occasion. So many of the cars that we saw parked at homes and on the road had body dents or a missing window.

As I awakened each of the five days, I would rise early and quickly from a firm bed in a dorm-like room. We all took turns making breakfast for the group. In my opinion, New Orleans, as a personality, was a hardened city. The city seemed mixed with affluence, manufacturing, hurricane damage, poverty, tourism and a surprisingly bold, rough aura. Unashamed, commercial lots were empty, abandoned, or half-occupied on occasion. So many of the cars that we saw parked at homes and on the road had body dents or a missing window.

Rolling white paint onto a ceiling, my task on the third of five work-days paled to the work we did the first day. Affixed to a dust mask, I looked out of the brand-new window that first day and was moved by the boarded-up, damaged home a few feet away from this in-progress home.

The first day I wore a dust mask and ear plugs, as we took on a house that Project Homecoming was committed to in one of the poverty districts. On that first day, each person found a preferred task. Some of the guys and girls preferred to use the back of a hammer and extract wood panels. Some of them spent time crawling under the home, recovering garbage of all kinds. Some of them liked to pry the nails out of the extracted wood panels, which I quipped was just like pulling teeth out.

Although I could not bring myself to crawl under a house and touch the many unidentifiable things under there, I certainly had a healthy appreciation for the young women, the graduate student staff advisor and the student, who works as a part-time waiter at a restaurant in DeLand, for removing the garbage and old pipes from the home’s underbelly.

And yet we bonded. Whether over Dubstep music, cooking a meal for the group at The Village, touring the French Quarter, practicing some Tai Chi, discussing philosophy, eating Po-Boys, or seeing the true New Orleans, we shared moments together and helped each other. Despite New Orleans’ vacant lots and empty houses with broken windows, the city’s vibrant culture impressed me. Observing a city in need, while traveling deeper into its core with booming electronic music that filled a white minivan of tired, paint-splattered volunteers, we all agreed that the lasting damage in New Orleans was unexpected and dominatingly unforgettable.

By Philip Yang