An Epic Quest: Photograph Every Native American Tribe

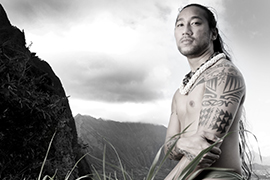

Matika Wilbur, a Native American of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes, once worked in advertising and celebrity photography before taking on a documentary assignment in South America.

That was when her grandmother came to her – in a dream.

“She sort of said, ‘What are you doing when you haven’t even worked with your own people?’ ” Wilbur recalled during a phone interview as she traveled by car in her native Washington state. “Of course, that really resonated with me.”

So Wilbur, who graduated from the Brooks Institute of Photography in California, began photographing her fellow Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. Then in December 2012, Wilbur packed up all of her belongings in her Seattle apartment, left behind “a boyfriend that I loved” and hit the road on an epic quest: to photograph citizens of all 562 federally recognized Native American tribes.

Wilbur will talk about her ongoing quest, which she dubbed Project 562, at Stetson University at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 29, in the Stetson Room of the Carlton Union Building.

Wilbur’s presentation will feature portraits of indigenous people from the 350 tribes she has photographed so far, including the Pueblo of Jemez, the Cherokee Nation, the Kanaka Maoli Independent Nation of Hawaii, the Northern Cheyenne, the Lummi Nation and others.

Since embarking on the project, she has averaged traveling 100,000 miles each year. Meanwhile, the federal government has added five more tribes to its list.

“I very much believe in the teachings my grandmother gave me while she was still with us,” Wilbur said. Her grandmother was a prominent tribal leader of the Swinomish, whose ancestral land is in the San Juan Islands off the coast of Washington. That gave rise to the tribe becoming known as “the people of the salmon.”

“One of the most fundamental lessons in indigenous cultures is the Creator gives us a gift and our goal is to share that gift and to use that gift for our people,” Wilbur said. “I was raised that way.”

Whether her prophetic dream “was my own self-consciousness reminding me of who I’m supposed to be, or whether it was my ancestor visiting me in the spirit, it’s literally one and the same for me,” Wilbur said. “The words, hopes and prayers of my ancestors live on inside of me. I don’t see myself as separate from those teachings or from my grandmother.”

In her artist statement, Wilbur writes that she believes Project 562 will be “the solution to historical inaccuracies, stereotypical representations and silenced Native American voices in massive-media.”

To that end, her photos will be accompanied by captions, video and audio recordings featuring “conversations about tribal sovereignty, self-determination, wellness, recovery from historical trauma, decolonization of the mind and revitalization of culture.”

Luis Paredes, Director of Stetson’s Office of Diversity & Inclusion, which is sponsoring Wilbur’s presentation, saw the photographer in San Francisco last June. There Wilbur was the keynote speaker at NCORE, the National Conference for Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education.

“I was blown away by her presentation style,” Paredes said. “With my team who were present, we said this is something we need to bring to Stetson. As we’re trying to diversify conversations of the ‘other,’ we thought bringing a Native American speaker is key — especially because of lack of representation in the media and the stereotypes associated with that population.”

Wilbur’s program is part of the Office of Diversity & Inclusion’s goal to “bring different dialogues of ethnicity and race beyond the binary that is constantly associated with the black and white perspective,” Paredes said. “Diversity inclusion is all kinds of differences that we encounter.”

“Decolonization is such a key word right now in academia and a populist topic among many Native communities,” Wilbur said. “It’s not as if I can speak for the entire Native American community, but what I’ve seen is many people are aiming to figure out what that means for themselves and their communities.”

Defining colonization, however, is a different matter: “When a person becomes colonized, they become stripped of everything they know and are forced into a new way of knowing,” she said.

Wilbur cited United States government policies that were “intrusive on American Indians’ collective culture.” Those policies included Native peoples forced to relocate from ancestral lands, Native children “being forced to speak a new language” and laws that made it “illegal for more than five Indians to congregate in a room and pray – it was considered a war party.”

Recounting such history led Wilbur to reflect: “What does it mean now for me as an individual to decolonize? I get to play one very small role in that. Just like it took hundreds of years for them to colonize us, it will take hundreds of years for us to decolonize. Each generation will have a new role to play. It’s like our grandparents planting the seeds of an apple knowing they would never see that tree grow to bear fruit that they can taste in their lifetime. But they planted it knowing their grandchildren would get to taste the sweetness and lusciousness of that fruit. There’s where we’re at right now.”

Through Project 562, “now it is my responsibility to rewrite history, not from the victors’ perspective but from the oppressed perspective, so our children can have the opportunity to know the truth and do not grow up with a sense of hopelessness and despair.”

If You Go

Native American photographer Matika Wilbur will present a program on her work at Stetson University at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 29, in the Stetson Room of the Carlton Union Building. Admission is free. Cultural Credit is available. For more information, contact the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at 386-822-7402.

— Rick de Yampert