SPREES Celebrates 60 years of Russian Studies at Stetson

In 1962, Ukrainian-born Serge Zenkovsky, the head of Stetson’s Russian Studies program since its founding in 1958, organized a Russian institute at the university.

Some area residents were not pleased.

“In the archives are letters from locals who went to the institute — it seems to have been a big DeLand event,” said Mayhill Fowler, Ph.D., director of SPREES, Stetson’s Program in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (formerly Russian Studies).

“Someone very anti-Communist wrote, ‘I just object to this event — it’s as if you’re saying that Communists have souls!’ ” Fowler said.

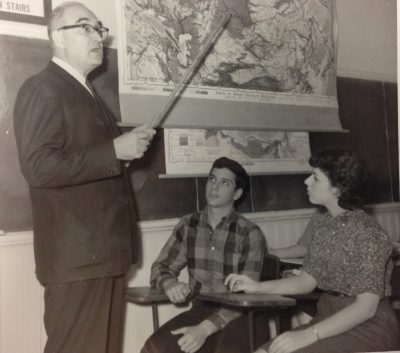

That letter, as well as other archival documents and photos, narrative panels, student remembrances and more, will be part of an exhibit celebrating 60 years of Russian studies at Stetson. The exhibit will have its opening from 3 to 5 p.m. Friday, March 16, at the SPREES House at 249 E. Michigan Ave., DeLand, with current students giving tours at that time. Cultural credit is available.

A panel discussion featuring four generations of SPREES alumni will be held at 6:30 p.m. March 16. Moderated by Professor of Political Science and SPREES faculty member Gene Huskey, Ph.D., panelists will discuss how Russian studies changed their lives. The panel will include former Pentagon worker Diane Disney, one of Stetson’s first Russian Studies students. Cultural credit is available.

“Obviously the point of the program, and this is true of most Russian and Soviet studies programs from that period, was not ‘fight the enemy’ – it was mutual understanding,” Fowler said. “It was trying to understand this very different place. Stetson has been at the forefront of undergraduate education in Russia since 1958.”

Fowler said she and fellow SPREES Professor Katya Kudryavtseva, Ph.D., who teaches art history, “spent a lot of time in the Stetson archives” researching the founding of Russian studies at the university, “but ultimately we never found a smoking gun-type document that explains everything.”

However, Fowler said, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite, in October 1957, it “was a big motivating moment for the spread of Russian Studies in the United States. We found a brochure with a quote from J. Ollie Edmunds, who was president of Stetson at the time, and it said something about we need to fight the Sputniks and Communists with education. And we found a lot of documents from the founding and hiring of Serge Zenkovsky, who was the first professor of Russian Studies brought to Stetson.”

Zenkovsky was an ethnic Russian from Kiev whose family left around the time of the Russian Revolution. He grew up and went to school in Paris, earned his Ph.D. in Prague during the Nazi occupation and emigrated to the U.S. after the World War II.

Zenkovsky was at Indiana University when he and his American-born wife, Betty Jean, “were wooed” to Stetson, Fowler said. At the time Stetson was affiliated with the Florida Baptist Convention. That affiliation played a role in landing the couple.

“He and his wife (who taught Russian language at Stetson) were quite religious, and they liked the idea of a Christian school,” Fowler said. “They also liked Florida.”

Serge Zenkovsky became one of the pre-eminent Russian scholars in the U.S. His career would include stints at Harvard, Vanderbilt and other universities.

Diane Disney had graduated from high school in southern Indiana and enrolled at Stetson in 1959 at the urging of her grandparents, who had retired in DeLand.

Disney was majoring in English but, she recalled, “I had been very interested in Russian literature in high school. And remember this was during the Cold War, so everybody was aware of the Soviet Union, which I found fascinating. So I took everything in Russian Studies that was possible to take. Effectively that was an extra major.”

Akin to that irate letter writer, Disney encountered people who questioned her motives.

“Admittedly there were some people who wondered why I wanted to learn Russian,” Disney said during a phone interview from her office at Penn State University, where she’s professor emerita of management. “I think phrases like ‘Commie Pinko’ came up in the conversation (laughs).”

While Disney believes Russian Studies has benefited her throughout her career in academia, government and the public sector, she noted her background in Russian language especially aided her at the Pentagon, where for seven years she served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Civilian Personnel Policy.

“One of the things in my purview was working with former Communist-bloc countries to help them develop programs to educate civil servants as executives so they could have civilian control of the military, which is a basic tenant of democracy and essential for them to have NATO membership,” she said.

The Zenkovskys left Stetson in 1967, and, after Paul Steeves arrived to direct Russian studies in 1973, the program began taking students to the Soviet Union in the late 1970s.

Huskey arrived at Stetson in 1989 and promptly established an exchange program with Moscow State University: Stetson students would attend the Moscow school to learn Russian, and that school would send professors to Stetson to teach for a year.

In the early 1990s under the guidance of President Doug Lee, the university received a $250,000 grant from the Knight Foundation, which was matched by the Jessie Ball duPont Fund.

“Basically, Doug Lee was allowed to pick any program to apply for this money, and he picked Russian Studies,” Fowler said.

The grants provided funds for visiting artists and lecturers, such as poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and writer Tatyana Tolstaya, the establishment of the program’s own house, a full-tenured track line for Russian language, and satellite television.

“Of course, satellite TV doesn’t mean anything now, but at the time having it so you could watch Russian language TV was pretty amazing,” Fowler said.

In 2014, the program changed its name from the Russian Studies Program to SPREES, Stetson’s Program in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies.

“After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian studies suddenly sounded weird,” Fowler said. “Did that include Ukraine? Kazakhstan? Belarus? Georgia?”

It took Russian Studies programs across the country time to “decolonize,” she said, but the new name for Stetson’s program, “while unwieldy, speaks to the complexity of the region. You can’t understand Russia if you only understand Russia — then you don’t understand why Putin is dealing with Ukraine, why there’s a Chechnya terrorist problem.”

SPREES has six tenured or tenure-track faculty: Michael Denner, Ph.D. (who teaches language and literature), Katya Kudryavtseva (art history), Daniil Zavlunov, Ph.D. (music history), Jelena Petrovic, Ph.D. (communication and media studies), Gene Huskey (political science), Snezhana Zheltoukhova (Russian language), and Fowler (Russian and East European history).

SPREES will have 12 to 20 majors in the program at any one time, Fowler said, while anywhere from 35 to 40 students will be taking Russian language courses.

With Russia constantly making headlines these days, SPREES “is absolutely more relevant than ever,” Fowler said. “We try to encourage students to think that Russia is not just Tolstoy, not just literature. It’s cyber security. It’s analytic linguistics. It’s working in D.C. Its high-level, high-paying jobs.”

– Rick de Yampert

If You Go

The 60th anniversary exhibit will be open 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday through Friday until the end of the semester at the SPREES House, 249 E. Michigan Ave., DeLand. The exhibit is open to the public.