Stetson Professor Gets Cooking with Georgian Cuisine

Present a lecture on the history of Georgia, nestled between Russia and Turkey, and no one would come, says Michael Denner, PhD, director of Stetson’s Program in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies.

However, he added, “People will come to a lecture on Georgian food.”

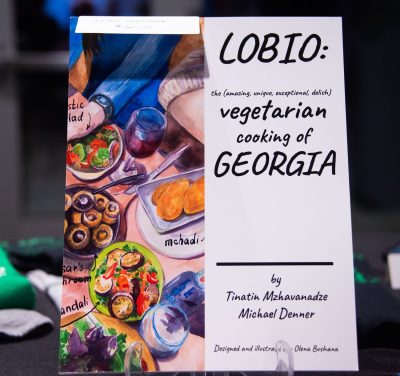

The SPREES professor should know. He wrote the book on Georgian cuisine: “Lobio: The Vegetarian Cooking of Georgia” is his translation and adaptation of “Georgia with Taste” by Georgian writer and culinary expert Tinatin Mzhavanadze.

The just-published “Lobio” (which means “bean” in Georgian) is available in the Stetson University Bookstore.

Denner became inspired to create an English-language version of the cookbook when he encountered it “while spending lots of time in Georgia five years ago.”

“Food is a great passport to other cultures,” said Denner, also director of the University Honors Program. “I got interested in the cuisine and the food ways of Georgia, and this was the best cookbook I found on Georgia cooking because it’s not highfalutin – it’s sort of down-home cooking.”

He showed the 600-page book, written in Russian, to a Georgian friend, who told him the author happened to be the wife of his son’s godfather. That connection began Denner’s working relationship with “Tina.”

“Georgians don’t use cookbooks,” Denner said. “All Georgians know how to make Georgian food. Georgian cuisine is not a recipe-driven cuisine, which is why this book is in Russian. It was intended for people in Ukraine and Russia and the former Soviet Union. This is an oversimplification, but it’s accurate: Georgian cuisine was to the Soviet Union what French cuisine was to American cooking. That is to say it was a sort of exotic, flavorful alternative cuisine.”

Denner acknowledges that the cookbook “may not be seen as properly academic and that’s fine. It’s not an academic publication, although it is. I’m trying to push the boundary of what people consider as academic.”

Pushing that boundary was evident when Denner gave a lecture on Georgian food Nov. 14 in the Lynn Presentation Room of the Rinker Welcome Center.

There was foodie talk, and attendees were invited to taste free samples of such vegan Georgian fare as Pkhali sushi (walnuts and cabbage), Badrijani (fried eggplant and walnut paste) and Khinkali (dumplings stuffed with winter squash). All were recipes from Denner’s book, and all were prepared by the DeLand restaurant, The Twisted Chopstick.

Denner also ventured into 6,000 years of Georgian history, the nation’s geography and its somewhat unique, Jekyll-and-Hyde identity crisis over whether it is European or Asian. And he explored the ways any nation’s food may embody “progressive” and-or “reactionary” politics.

“Scratch any two-cent dictator . . . and you’ll find a little boy sweatily holding his fork ready to tuck in,” Denner said during his lecture. “So much of frankly nationalistic identity is bound up in food. I really don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that the most rabid nationalist would be satisfied at least for a minute with a meal that grandma made.

“In this sense, food is reactionary and regressive. It’s so often at the center of discussions of identity and ethnos. And so it runs cornerback to globalism’s offense,” he said.

Elizabeth Skomp, PhD, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and a professor of Russian, said in her introduction that “there is an academic food studies component” to Denner’s work.

She expressed her glee over his in-the-kitchen work by giving a personal anecdote: “I visited St. Petersburg (Russia) in the 1990s and ate a soup that is a staple of Georgian cuisine. That soup marked my initiation into a new set of culinary experiences. I might have been rhapsodizing earlier today about how excited I was that Georgian food was going to attain a greater visibility and following on campus, thanks in large part to the work of Professor Michael Denner.”

And so academia and gastronomy reside side by side in “Lobio.”

“You can’t possibly talk about Georgian food without talking about the history of Georgia, the geopolitics of Georgia, the geography of Georgia, the culture of Georgia and it goes on and on,” Denner said after his lecture.

Denner realized he had to whittle down Mzhavanadze’s massive tome, so he decided to focus on vegetarian and vegan cuisine because “I think what Georgians do with vegetables is just really unique and interesting.”

“Lobio” is “more than a cookbook,” Denner said. “It was written by Tina and by me as something you could sit down with and read from cover to cover. Each of the recipes has stories, each of the recipes has history, each of the recipes has commentary on Georgian politics and culture.

“It’s a book to cook from — the recipes are great and the food is tasty. But it’s also a book to read and learn from,” he said.

— Rick de Yampert