Volusia Remembers Racial Terror Lynching on Saturday

“Negro Driver is Lynched for Killing Child,” said a headline in a Nevada newspaper in April 1939.

The national news media was following the case of Lee Snell, a Black World War I veteran and owner of a Daytona Beach taxi service, who was lynched after his taxi accidentally hit and killed a 12-year-old white boy on a bicycle.

A constable was driving Snell to the County Jail in DeLand when his vehicle was forced to stop along the old brick highway between Daytona and DeLand. Two white males dragged Snell from the vehicle, beat him and shot him multiple times.

Snell is one of five lynchings documented in Volusia County. And he will be the first victim honored locally in a virtual ceremony set for Saturday, Feb. 27, at noon. Register for the webinar.

The Volusia Remembers Coalition, made up of community leaders as well as Stetson and Bethune-Cookman University faculty, staff and students, will host a Soil Collection Ceremony at the site where Snell is believed to have been murdered and eventually will install a historical marker there.

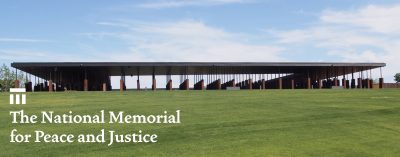

Volusia Remembers is working in partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that has documented 6,000 lynchings and counting between 1877 and 1950 in America. The names of the victims are inscribed on EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, and the jars of soil from the lynching sites are displayed on exhibit.

Community leaders like Daisy Grimes, Ceremonies Chair for Volusia Remembers, say they hope the project educates America about the history of racial lynchings, which deprived Blacks of their right to a fair trial.

“We need to acknowledge it. We need to confront it and we need to say it was wrong,” said Grimes, a longtime community activist in Daytona Beach. “And until we do that as a country, we’re going to have problems because we’re still doing it today.

“We’re killing people and we don’t even know if they’re guilty or innocent because we don’t give them that opportunity,” she added.

In Snell’s case, he served in the U.S. Army during WWI and returned home to a hero’s welcome. He was a family man, a non-drinker and member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. It isn’t clear if his taxi struck the boy, or the boy collided with the taxi, according to the Volusia Remembers website and accounts at the time. But he never had his day in court, murdered before he could stand trial on a charge of manslaughter.

The white constable initially identified Snell’s attackers as the white boy’s two older brothers, and they were charged with murder.

At their trial, with an all-white jury, all-white attorneys, a white judge and segregated seating for blacks in the balcony, the constable changed his story and said he “might have been mistaken” about their identities and was “under great mental strain,” according to a newspaper account of the trial. The brothers were acquitted, reinforcing perceptions that Blacks could be killed with impunity.

The documented lynchings in Volusia County motivated members of the Stetson community to action. Rina Arroyo, assistant vice president for Development, Parent and Alumni Engagement, recalled going on Stetson’s Summer Civil Rights Travel Course, visiting historic places in the Civil Rights Movement. She took the trip in 2018 with late Religious Studies Professor Greg Sapp and others from the College of Law, not long after the national memorial opened in Montgomery.

Arroyo remembered the “overwhelming sense of horror” as she stood among the memorial’s 800 hanging monuments, engraved with the names of lynching victims, including four from Volusia County. “I recall the shock I felt when I realized that I, a 50-year-old white woman who grew up in Nebraska, was not taught about the brutal truth which was so visible to me now as I moved through the erected monuments,” she said.

Stetson faculty and staff soon joined efforts with community leaders, including the group’s co-chair Sharon Stafford, to research lynchings in the community, honor victims with ceremonies and place historical markers at the sites.

Andy Eisen, PhD, visiting assistant professor of history at Stetson, and his students conducted research, as well as Richard Buckelew, PhD, a history professor, and his students at Bethune-Cookman University. Members of Stetson’s Black Student Association also have volunteered on the project.

Through research, the group brought the lynching of Lee Snell to the attention of the Equal Justice Initiative. EJI requires documentation, such as court records and newspaper accounts, before adding a victim’s name to the memorial.

Snell’s case had received extensive media coverage, which often used the word, “lynching,” in the headline. EJI agreed right away to add his name to the national memorial, bringing to five the number of documented lynchings in Volusia so far, said Professor Emeritus Grady Ballenger, PhD, co-chair of Volusia Remembers.

The ceremony to honor Snell also will be shown Feb. 27 during a three-day conference by Zen Peacemakers International about “Race in America.” Stetson University Chaplain, Sensei Morris Sekiyo Sullivan, is helping to coordinate that event. Endowed Chair of Social Justice Education at Stetson, Rajni Shankar-Brown, PhD, was invited to serve as a Keynote Speaker for the conference.

Shankar-Brown will be discussing the caste system and illuminating persistent and invidious racial inequities through intersectional lenses in the United States. She will weave personal narrative, research and teachings from Isabel Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of our Discontents,” as well as visual art and original poetry.

According to Shankar-Brown, “It is imperative that we individually and collectively commit to being anti-racist in all aspects of our lives. Racial justice demands truth, love, liberation, reconciliation and reparations. We need to engage in continuous reflection, listening openly and deeply, unlearning and learning, and actively disavow racism, as well as classism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, xenophobia, religious discrimination, and other forms of oppression rooted in colonialism and the patriarchy. I am grateful and looking forward to being a part of this critical plunge on ‘Race in America,’ thoughtfully organized by Zen Peacemakers International.”

Shankar-Brown also will read an original poem honoring Snell at the Saturday’s ceremony. Sam Houston, PhD, Brown Visiting Teacher-Scholar Fellow in Religious Studies, Assistant Professor of Digital Arts Chaz Underriner, PhD, and Stetson students will coordinate streaming of the ceremony.

Ceremonies will be planned at Volusia’s other four lynching sites. And the group continues to research others reports of lynchings, although none so far has met EJI’s standards for documentation.

“It’s important to us that we’re careful in our documentation,” Ballenger explained. “But we also say these are representative examples of a system of unequal justice, of terror, during this time of anti-Black racism following the Civil War.

“So, even those that we can’t put on that (memorial) column at this point, at least we can talk about them as further evidence of what our Black brothers and sisters have had to live with. For me, it’s history, but for many members in our coalition, it’s a matter of family history, personal history.”

Volusia Remembers also hopes to foster dialogue about the racial injustices and provide, “ultimately acknowledging the hard work it will require, a kind of apology and reconciliation,” he added.

-Cory Lancaster