‘You are not forgotten’: Community Education Project students create ‘Slavery and the Struggle for Freedom’ exhibit

In 2018, Andy Eisen, PhD, visiting assistant professor of history, was disturbed by what he saw – or rather, what he didn’t see – during a trip to DeLeon Springs State Park.

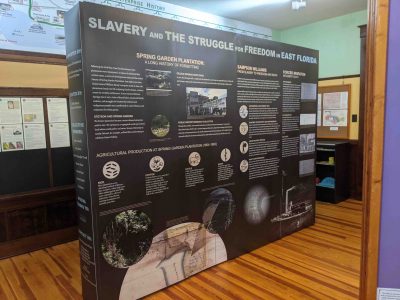

The local history exhibit at the park, a mere eight miles from Stetson’s campus, “failed to acknowledge the history of enslaved persons in any meaningful way,” Eisen said. “In fact, one of the two panels that focused on slavery callously claimed that the lives of enslaved persons were simply quote-unquote long forgotten. The rest of the exhibit did much to aggrandize and center on the lives of white settlers and enslavers.”

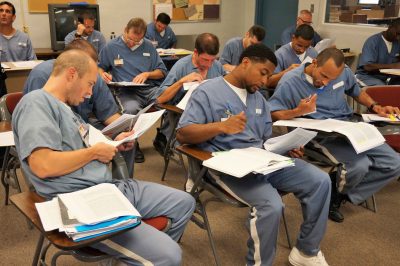

Eisen also is co-director of the Community Education Project, Stetson’s college-in-prison program which operates at the Tomoka Correctional Institution in Daytona Beach. When he presented a program on his DeLeon Springs experience to one of his classes at the prison, “our incarcerated students asked, ‘What can we do about it?’ And so the Public History Research Collective was born.”

One of the results of the collective’s efforts can be seen in the exhibit, “Slavery and the Struggle for Freedom in East Florida,” which is on display through March at the Enterprise Museum. Eisen spoke about the research of the collective, which includes himself and six incarcerated students, during a virtual talk on Tuesday, March 16, as part of Lost History Week at the museum. The event also included attendees socially distanced onsite at the exhibit.

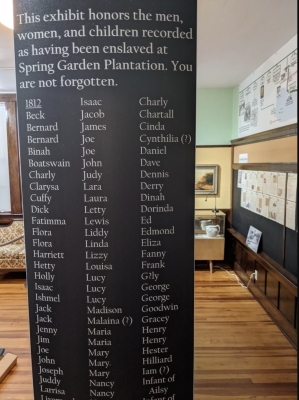

“Through their close study of transcriptions of shipping manifests, probate records, diaries, maps and the census,” the collective uncovered the names of more than 230 people enslaved in the mid-1800s at the site of the state park, at what was then the Spring Garden Plantation, Eisen said.

Detail from the exhibit, “Slavery and the Struggle for Freedom in East Florida.” Photo by Maggie Ardito

Eisen read a reflection from incarcerated researcher Antonio Rosa, “who has been instrumental in moving this project forward,” the Stetson professor said. Rosa wrote: “Enslavers . . . generated inventory lists, bills of sale, deeds, wills and journals in which they commodified enslaved persons. These same records silenced them by representing them as chattel, as opposed to persons suffering an injustice. (These records) fail to tell us anything meaningful about enslaved subjectivities and lived experiences . . . But by reading records against the grain, Stetson CEP’s public history project is teasing out lived experience from the slaveholders’ silences.”

A long, vertical panel at the museum reads: “This exhibit honors the men, women and children recorded as having been enslaved at Spring Garden Plantation. You are not forgotten.” All of the names are listed.

Lost History Week

Lost History Week also included “William Bartram: Creating Wilderness,” a virtual and onsite lecture by Tony Abbott, PhD, professor of environmental science and studies, on March 18.

Bartram was an American botanist, ornithologist and natural historian known for his explorations in the 1770s of what would become the southern United States. The exhibit, “Maps, Guides, Bartram’s Art and History,” also is on display at the Enterprise Museum through March. Abbott has retraced Bartram’s travels across Volusia County and created the brochure guide, “Experience William Bartram’s Florida.”

Lost History Week was presented by the St. Johns River-to-Sea Loop Alliance as part of its River to Sea Nature and History Corridor project, which is supported by a community project grant from Florida Humanities, said alliance president Maggie Ardito.

The alliance’s mission is to support and protect the St. Johns River to Sea Loop, a 260-mile Florida paved trail, and promote environmental, cultural and historical awareness of the trail and nearby communities. She noted that the lectures and exhibits of Lost History Week were created independently of the alliance, but added the alliance website has digital maps of how the relevant places cited in the lectures can be reached from regional trails.

“An active process of erasure”

During his virtual talk, Eisen said he believes “the word ‘lost’ is a bit too passive. It suggests a process of happenstance or perhaps accident the same way someone might displace their keys or their wallet. Instead, I think it may be better to understand this is an active process of erasure.”

Eisen showed a photo he took at DeLeon Springs State Park in January 2016 when “the Sons of the Confederacy gathered and they planted their flags, joyfully re-creating what they call the War Between the States. I don’t know the full story of how the exhibit at DeLeon Springs came to be, but I do believe there is a direct connection to presenting white idealized versions of the past that carelessly render the lives of enslaved persons simply as long forgotten. In many respects a story being told is not about a lost history but rather one that simply has not been searched for.”

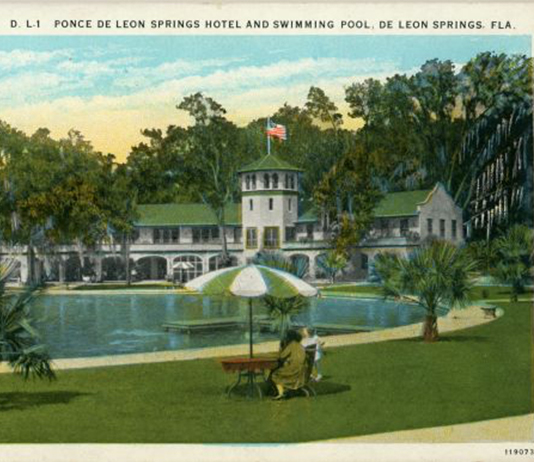

Eisen quoted research by his students that is included on an exhibit panel: “Just eight years after Union Gen. William Birney’s surprise attack in 1864, the plantation found new life as Spring Garden House, a winter resort for wealthy Northerners. It was renamed DeLeon Springs Inn in 1925. A site of forced labor, sexual and family violence, and struggle for freedom by enslaved and indigenous peoples was transformed into a site of leisure and enjoyment for white guests.”

Eisen also noted that a mural on the Morgan Stanley building in downtown DeLand is based on a 1915 photo of two white people at DeLeon Springs State Park, “or the Old Sugar Mill as it is sometimes referred to, which is a euphemism for plantation,” he said. “This image, according to a visitors’ guide from the West Volusia Tourism Bureau, shows the mill as a favorite location for a family picnic spot. What had been one of the largest and most profitable plantations in East Florida at the time of the Civil War is remembered instead as being a quaint spot for white folks to picnic.”

The museum exhibit includes a colorized photo of Stetson University students enjoying Hatter Holiday at the springs in the 1950s.

Along with Rosa, the collective’s incarcerated student researchers, whose names are featured prominently as part of the exhibit, include Roger Cassidy, Derrick “Mustapha” Ford, Mercury Kane, Kenneth Smith and Pete Storrs. Some of the students are featured in the documentary film, “Unsilenced: Rewriting History from Prison,” which was screened as part of Eisen’s program.

Eisen shared some of his students’ research.

He quoted Smith’s writings on the Second Seminole War: “Did you know that the first Underground Railroad did not travel north but south into Spanish Florida? What about the fact that this pathway to freedom led to not only the creation of free productive African societies in Central Florida, but also a unique Afro-Indian alliance that fought for and won the emancipation of some enslaved people before the Civil War.”

Kane’s research led to the discovery that two of the enslaved people at Spring Garden Plantation, Anthony Starke and his sister Amelia Roper, have a descendent named Leon Clements who today lives in the area: “We presented our research to Mr. Clements,” Kane wrote. “He was unaware that Anthony Starke was one of his relatives and that his family could be traced to a plantation only 20 miles from where he grew up. Mr. Clements had assumed that his family moved down to Central Florida from South Carolina following the war.”

Eisen noted he has “been able to take the research of our incarcerated students and share it with our Stetson University students at the Deland campus.” In 2019, he led a tour of the plantation with students from the campus, “and much of what I shared with the students that day was directly from the research that our incarcerated scholars had uncovered.”

At the end of the tour, Eisen said, he and the students “walked away from the busy area with people swimming and the pancake house calling out names of people waiting to dine. We found a quiet trail, and in a very simple, thoughtful way students read all of the 230-plus names of the men, women and children who were enslaved at what is now DeLeon Springs State Park. It was one of the most powerful teaching moments of my career.”

— Rick de Yampert