Coronaviruses and the Science of Spillover Diseases from Animals

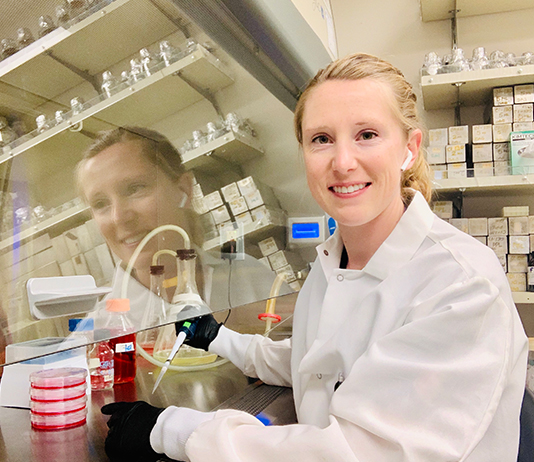

On the first day of her virology class, Assistant Professor Kristine Dye asks students how much information in the news do they think is accurate about coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19.

Students usually estimate 20% to 40%. They are surprised when Dye, a virologist with a PhD in pathobiology, tells them “probably less than 5%.”

Dye wants students to learn the facts in a class called, “The Virology of Spillover.” Viruses have been spilling over from animals to humans for thousands of years, causing deadly outbreaks of malaria, influenza, Ebola, HIV and other diseases.

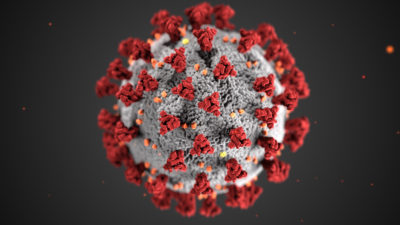

The frequency of these spillovers is accelerating, due to the pace of human activity around the globe, such as clearing wilderness, which brings people into contact with animals and their pathogens. This is especially true for coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2.

“This is the third, highly pathogenic coronavirus spillover in the past 17 years, with SARS being in 2003 and MERS being in 2011,” Dye explained.

Humans: A Target for Spillover Diseases

Coronaviruses evolved with bats over millions of years and do not cause disease in those animals. But humans, whose immune systems have never seen these coronaviruses prior to the spillover, don’t have pre-existing immunity, allowing for potentially high rates of transmission and severe disease.

The 2003 SARS-CoV spillover was traced from bats to civets to humans while the 2011 MERS-CoV outbreak was traced from bats to camels to humans. Experts still are trying to determine how SARS-CoV-2 crossed over into humans in late 2019.

“Spillover is a completely natural process that doesn’t just happen to us, but also because of us,” Dye explained. “Humans share this planet with many other species, all of which have microorganisms that need to infect a host and transmit for survival.

“Our abundance, activities and behaviors make us – humans — a prime target for spillover. Although they will continue to happen, we can mitigate the outcome by learning how to predict and prepare for these spillovers, and educate the public on how to respond. Spillover will keep happening, but human behavior will determine the extent, severity and outcome,” she added.

Four coronaviruses, for instance, cause common colds in humans. These viruses probably first crossed over to humans thousands of years ago and may have caused deadly pandemics at the time. But over time, the viruses mutated again and again, infecting humans again and again, until those who survived developed a protective, lasting, immune response, leading to the mild illness we know today as the common cold.

Vaccines provide this same immunity for people, just far quicker, while also avoiding serious complications of natural infection, including death. As the omicron variant surges, experts say people who have been vaccinated and received a booster suffer only mild symptoms – mostly sore throats, Newsweek magazine reported Jan. 5. People who are unvaccinated can suffer the worst symptoms and even require hospitalization.

Dye said about COVID-19 variants, “You’ve heard people having breakthrough infections. It is normal for a vaccine to not provide 100% protection from infection, but instead significantly reduce disease severity and death. Those with breakthrough infections typically have a stuffy nose, maybe a slight cough, what you would normally see in the common cold season.

“Vaccines are a technology that have allowed us to accelerate reaching equilibrium with the virus, while also avoiding many hospitalizations and deaths along the way. Pandemics from spillover have happened since humans first evolved. I am glad to live during a time when we have the knowledge to fight back,” she continued.

The Virology of Spillover Diseases

Dye has been fascinated by virology since her junior year at Brigham Young University – Idaho. One of her professors recommended the 2013 book, “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic,” by David Quammen.

“That’s what really prompted me to go into virology,” she said. “I like to tell students that story because many students look at their professors and think that we knew what we wanted to do since we were two years old and that’s not the case at all.”

After earning her PhD in pathobiology from the University of Washington in Seattle, Dye interviewed for a faculty position at Stetson in February 2020. She was already designing a class on spillover before the world realized the magnitude of death and upheaval that would be caused by COVID-19.

“A lot of people think that this class was made for the pandemic, but it was made before then. As a virologist, I like to say, ‘I will be teaching this class long after the COVID-19 pandemic is over.’ Spillover was a global health concern before this pandemic and will continue to be a global health concern after this pandemic. There will be more. There will always be more,” she said.

“We’re going to be living with SARS-CoV-2 most likely the rest of our lives, but with widespread vaccination, it’s most likely going to become the fifth common-cold coronavirus.”

Deadly Misinformation

Dye has been surprised by the vast amount of misinformation about COVID-19, adding that “unfortunately misinformation does kill.” For example, according to one myth, the vaccine can cause infertility and miscarriage, which has made many pregnant women afraid to get vaccinated in fear of harming their unborn baby. But these claims have no basis in science, according to the American Medical Association.

In fact, unvaccinated pregnant women are 15 times more likely to die if they get infected with COVID-19, a statistic that unfortunately is not heard by many, unlike the myths described above.

“Every single time I go to a hospital, I talk to OBs (obstetricians) and they say they have two women on life support downstairs who are pregnant and they’re trying to keep them alive,” Dye said. “And it’s just really sad, the kind of misinformation that’s being spread around.”

She wants to educate Stetson students about the facts, ensuring they can make good decisions in their own lives, educate those around them and also prepare for careers in health care.

“Unfortunately, a lot of healthcare professionals have left their practice because of this pandemic. But there is a huge influx of students who are studying right now and going into the healthcare professions,” she said. “This is a great opportunity to teach them the truth regarding infectious disease because, like I said, it’s going to happen again.”

-Cory Lancaster