The Story Behind the Sounds

Editor’s note: This article appears in the Summer/Fall 2024 issue of Stetson University Magazine.

The organ in Stetson’s Lee Chapel was built in 1961 by the firm of legendary organ builder Rudolf von Beckerath of Hamburg, Germany. School of Music Professor Paul Jenkins was the leader of the historic project, having become familiar with Beckerath’s work through the first American Beckerath organ, which today remains in a Cleveland, Ohio, church.

At the time, it was a rather revolutionary choice for our university. American builders had been building instruments with insensitive electric key action for many years, enamored of the possibilities brought about by modern electric technology. The selection of a classically designed mechanical key action organ, encased in reflective housing, represented a return to the design ideas of previous centuries, exemplified by many historical instruments throughout Europe.

In fact, Stetson’s Beckerath organ was the first such instrument (encased, with mechanical key action) in an American university’s primary performance space. There had been the Cleveland Beckerath and a Dutch Flentrop organ at Harvard University, housed in an art gallery. Stetson’s organ became a revelation to a generation of organists, who still hold it in high regard both as an instrument of excellence and as a historical monument.

The organ consists of 36 stops, 54 ranks of pipes and more than 2,700 pipes in total.

In late January, College Cliffs, a provider of higher-education rankings, included the Beckerath organ among its “20 Oldest and Most Amazing Organs in College Campus Chapels.”

My first encounter with the organ came in my senior year of high school. I was living in Louisville, Kentucky, and was studying with a fine organist, James W. Good. Dr. Good normally taught graduate-level students, yet had taken me on. He was invited to do a guest recital at Stetson, and suggested that I come with him to meet Professor Jenkins and experience the organs here. The year was 1971.

As a teenager, I had many recordings of the great European organs. I also had lots of recordings of rock bands. I practiced on large American-made electric-action organs, buried in chambers in churches in Louisville. I had heard several famous rock bands in concert, and noticed they never seemed to sound as good as the recordings. The same seemed true of organs. None that I had played or heard came close to the glorious, living, breathing sounds of the great European organs on recordings. I just assumed that nothing sounded as good in person as it did on recordings. I vividly recall first hearing the Stetson Beckerath organ and thinking, “Oh, my! Organs really can sound that good!”

I ended up attending Stetson, and Professor Jenkins became my mentor, and remains the most influential teacher I ever had, despite my later study at Yale University and abroad. I know that scores of his former students, many of whom went on to the most distinguished graduate schools, share this assessment of his teaching prowess. He served as professor of organ in the School of Music from 1956 to 1993.

It has always seemed to me that such a then-radical choice for an organ in an academic institution could have only been made at a school like Stetson, where the decision could be made by one professor, one dean and one president. Schools still have trouble getting fine organs. Given the large costs, they often confront preferences for “lowest bid” considerations, preferences for nearby builders and committees making decisions without being really well-informed.

Rudolf von Beckerath was a builder of enormous importance. His organs are in several countries. He had apprentices who have gone on to be the heads of some of the most important organ-building firms around the world, including in the United States. He passed away in 1976, but his firm continues in Hamburg.

After Stetson, many schools acquired similarly excellent instruments. The next U.S. Beckerath, after ours, was built at the University of Richmond. In 1971, the same year that Stetson acquired a Beckerath studio organ, Yale University had an instrument similar in size to the Lee Chapel organ built in their Dwight Chapel, in the center of the campus.

Generations of students have learned from Paul Jenkins, and I hope from me, and also from the instruments here. In the case of organ study, people learn at least as much from the instruments they are able to study and practice on as they do from a professor.

We are fortunate at Stetson to have a total of six organs by Beckerath. The studio organ is a bit more than one-third the size of the Lee Chapel organ, and the others are small practice organs. All are still in excellent condition, and all possess the same key sensitivity that is so essential for refined organ study and performance.

The Lee Chapel organ is well known in the broader organ community. It seems an inevitability that guest recitalists will conclude their performances by bowing first to the audience, and then to the instrument. The organ here is arguably the finest work of art the university possesses. Later work provided an update to the case design. When the organ was built in 1961, the case of the instrument was a very plain Bauhaus-style German case design, as no expense was wasted on visual aesthetics. Years later, noted organ-case designer Charles Nazarian provided new encasement, without disturbing any of the acoustical aspects of the original design. He was attempting to do what Beckerath might have done had there been no budget restrictions in 1961.

The casework is fascinating, including an “egg and dart” motive found in the proscenium arch of Lee Chapel, column design from the chapel’s interior, relief work copied from the exterior of Elizabeth Hall, “dental” work taken from the building’s design detail, and recurring shapes also employed on the exterior.

It has been an enormous privilege to learn on, teach on and play on this magnificent organ. It comes from what is considered the “sweet spot” in Beckerath’s building career (late 1950s to early 1960s). It is perfectly matched to the room’s acoustics in design, pipe scaling and voicing.

A restoration of the interior of the room about 20 years ago (with new wood for the seating, stage floor, etc.) required technicians from Beckerath to return and do subtle revoicing to have the instrument remain perfectly married to its surroundings.

The organ has been lovingly maintained, and remains a significant example of one of the greatest 20th-century organ craftsmen. I am honored to be associated with such an exemplary organ.

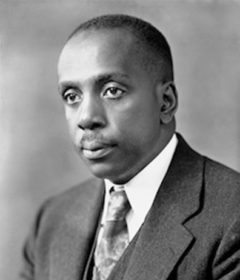

A 1975 alumnus, Boyd Jones, DMA, is now the Stetson University organist and the John E. and Aliese Price Professor of Organ. In addition, Jones performs extensively throughout the United States on both organ and harpsichord.