National Expert Tony Banout Addressed ‘Wrongheaded, Immoral, and Offensive Speech’ on Oct. 28

Tony Banout is the inaugural executive director of the University of Chicago’s Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression. Previously, for more than a decade, he had served as the senior vice president for Interfaith America, guiding the civic organization in the development of strategies and programs devoted to democratic discourse and civil conversation across deep difference.

As such, Banout stands comfortably as a recognized national expert.

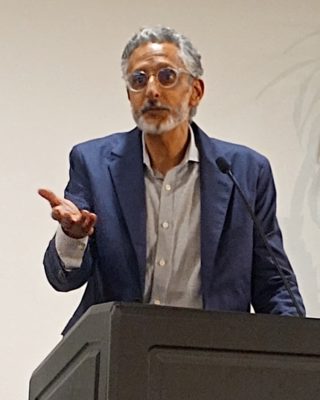

On Tuesday, Oct. 28, in the Warren and Barbara Carr Stetson Room on campus, Banout’s proficiency was both on display and put to the test. Fully acknowledging the inherent complexities and controversial nature of his topic — including the title of his presentation — Banout addressed “Why is Wrongheaded, Immoral, and Offensive Speech Protected on Campus and Constitutionally?”

His address was part of Stetson’s Free Inquiry & Expression and the Future of Democracy Series.

Banout began: “Words are powerful, speech is powerful, expression is powerful. It follows then that just like any powerful reality, free speech can be used for good or for ill. Why, then, do democracies enshrine and abide by protections for speech that is used to hurt or offend? Why protect that which can dehumanize and debase? This question is my central concern this afternoon. The answer, I believe perhaps counterintuitively, is that a just democratic society requires free speech as foundational to justice and democracy. Therefore, our democratic society should protect free speech.”

Then, using historical references that date back centuries, Banout explored justice and social justice. “Justice is about both the basic arrangement and how we assess, argue for and change particular laws,” he said. “And it is absolutely about the ability and freedom that individuals have to challenge those laws. I believe each human has dignity, and I believe democracy is a system of government that most uplifts those givens — by treating each citizen as an equal or participating member of the political community. Thus, democracy as a social arrangement, with all its messiness and all its imperfections, is itself a question of justice. … Democracy is what is at stake when we deny free speech. None of this means that there will be no offensive or harmful speech, but it does mean that even such speech deserves legal protection.”

On the subject of free expression on campus, Banout drew parallels between Stetson and his University of Chicago, noting both are private institution. “Unlike a state school or a community college, [a private institution] is not a government entity,” he said. “As such, the First Amendment technically does not govern campus life or campus speech [at private institutions]. This, of course, does not mean that private colleges and universities are opposed to First Amendment. It simply clarifies that the First Amendment is not the foundation that governs the privileges you have as a member of the campus community.”

He cited Stetson’s mission of liberal learning that stimulates critical thinking, imaginative inquiry, creative expression and lively intellectual debate. Then, again pointing to the labyrinthine nature of the topic, he added: “I don’t see how you have liberal learning without free expression — I just don’t think it’s possible to understand free expression on campus.”

Appropriately, Banout’s speech was followed by an lively Q&A with attendees. As hoped for with this ongoing Stetson series to foster civil and open dialogue, there were more questions than answers.

-Michael Candelaria