Foreman Biodiversity Lecture: Planning for sea level rise

By Taylor Allyn

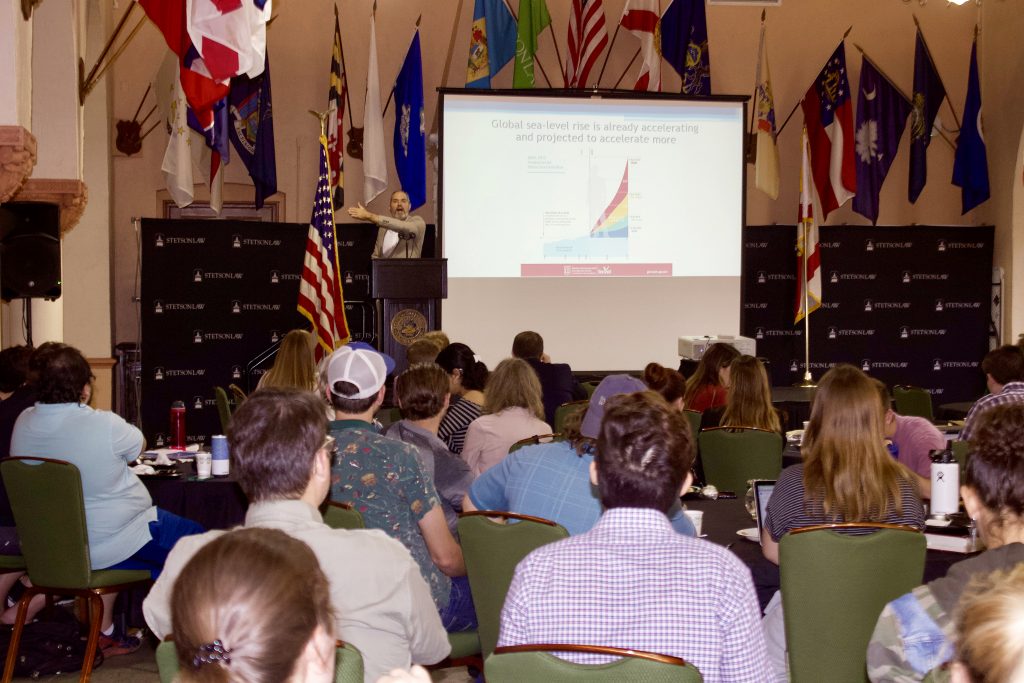

Dr. Jason Evans spoke on Nov. 5, 2019, as part of the Foreman Biodiversity Lecture series. Evans is an associate professor of Environmental Science and Studies and the interim director of the Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience at Stetson University in Deland. His recent research focuses on sea level rise vulnerability assessments and adaptation planning for coastal communities throughout the Southeast.

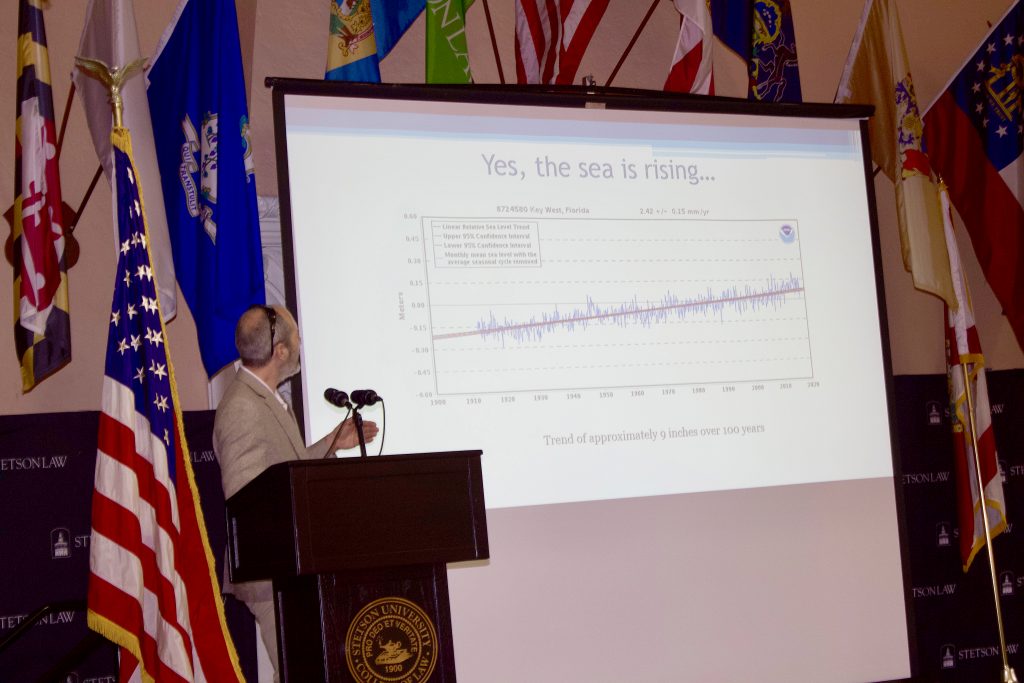

Evans kicked off his lecture with an explanation of some of the data behind sea level rise. In Key West, the sea level has risen 9 inches in the past 100 years. In Ft. Myers, it’s risen 12 inches in the past 100 years. Sea levels rise as the climate warms, resulting in warmer water that expands in volume. Melting ice also contributes, providing more water mass and volume. However, the sea level is not rising equally everywhere: It’s rising in many areas but falling in others because of rebounds from the weight of ice sheets as they melt.

Stark examples of saltwater flooding as a result of sea level rise have occurred in the Southeast.

“This last October there was flooding in certain areas [of the Florida Keys] for 45 straight days – where even at low tide there was still saltwater on the roads,” Evans said.

In 2015, Tybee Island, Georgia, had the fourth highest tide on record and the only road on or off the island became completely impassable. Saltwater flooding is not only harmful to vehicles and homes but presents a public safety issue when main roads are obstructed. We have experienced the fastest rate of sea level rise in 8,000 years – 8 inches over the past 100 years, Evans said. Climate projections predict a maximum of 10 feet of sea level rise by 2100. More conservative predictions expect an average of 2-3 feet by 2100. According to Evans, because the Earth has a naturally unstable climate, exact predictions are difficult.

“When it starts flooding, there is water coming out of a storm drain [and] the streets are flooding, who are you going to call? You are going to call the mayor, you are going to call city council, and those people are going to have to deal with it and figure out what to do.”

Evans stressed the role of local governments in sea level rise adaption and planning, because there is no national or even statewide policy capable of addressing this problem. He then introduced an analogy of a garden shed versus a nuclear power plant. With a garden shed in your backyard, you don’t really need to plan for sea level rise. A shed is cheap and will likely be gone by 2100. With a nuclear power plant, the stakes are much higher. There is zero tolerance for a plant failure, and it needs to be resilient to even the slightest risks. In that case, you need to plan for the worst.

Sea level impacts on the built environment start with stormwater drainage and wastewater infiltration, Evans explained. When the sea level rises, saltwater enters stormwater drainage systems and forms a plug. When it rains, fresh water cannot drain and just comes back up. For this reason, stormwater mapping is immensely important.

Evans worked to map high tide and flooding scenarios for St. Marys, Georgia, and the city later implemented green infrastructure stormwater improvements to address potential issues. Evans calls improvements like these “duct tape adaptation.” They are temporary fixes and won’t help much if the sea level rises 6 feet, but they can help avoid flooding in the meantime.

Evans wrapped up his lecture with a discussion of flood insurance and the Community Rating System (CRS), which is a voluntary incentive program for local governments to address climate change and sea level rise. By participating in the program and addressing sea level rise in their area, governments can receive a discount on flood insurance. Monroe County, Fla., was the first jurisdiction in the country to use sea level assessments to get a CRS discount. Programs like this can heighten the importance of sea level rise planning and risk assessment when larger policies are nonexistent or insufficient. Once the science behind sea level rise is accepted and governments start to address these risks, statewide and nationwide planning can begin.

About the Foreman Biodiversity Lecture Series

Stetson Law’s Institute for Biodiversity Law and Policy serves as an interdisciplinary focal point for education, research and service activities related to global, regional and local biodiversity issues. The Foreman Biodiversity Lecture Series brings to campus numerous experts in environmental law and environmental science. You can view Evans’s complete lecture on the Stetson Law YouTube channel.

Post date: Nov. 9, 2019

Media contact: Kate Bradshaw

[email protected] | 727-430-1580