Domestic cats an invasive species? The last biodiversity lecture of spring 2020 examines the issue

Arie Trouwborst, associate professor of environmental law at Tilburg University in Tilburg, the Netherlands, gave the final Edward and Bonnie Foreman Biodiversity Lecture of the spring semester on April 1 as part of the 20th International Wildlife Law Conference. The event, originally planned for two days on Stetson Law’s campus in Gulfport, switched to an entirely virtual platform because of the COVID-19 pandemic, so Trouwborst delivered his lecture via GoToWebinar.

His topic is a controversial one: Domestic Cats and International Wildlife Law – Turning a Blind Eye to One of the World’s Worse Invasive Alien Species?

Regardless of how one feels about Trouwborst’s research conclusions, one fact is indisputable: “Cats hunt and kill wildlife,” he said.

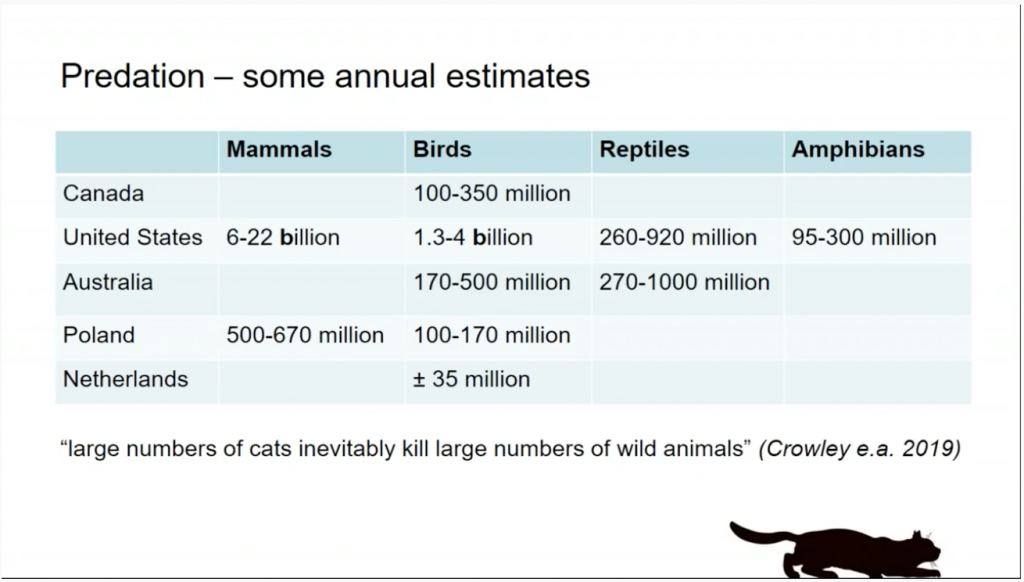

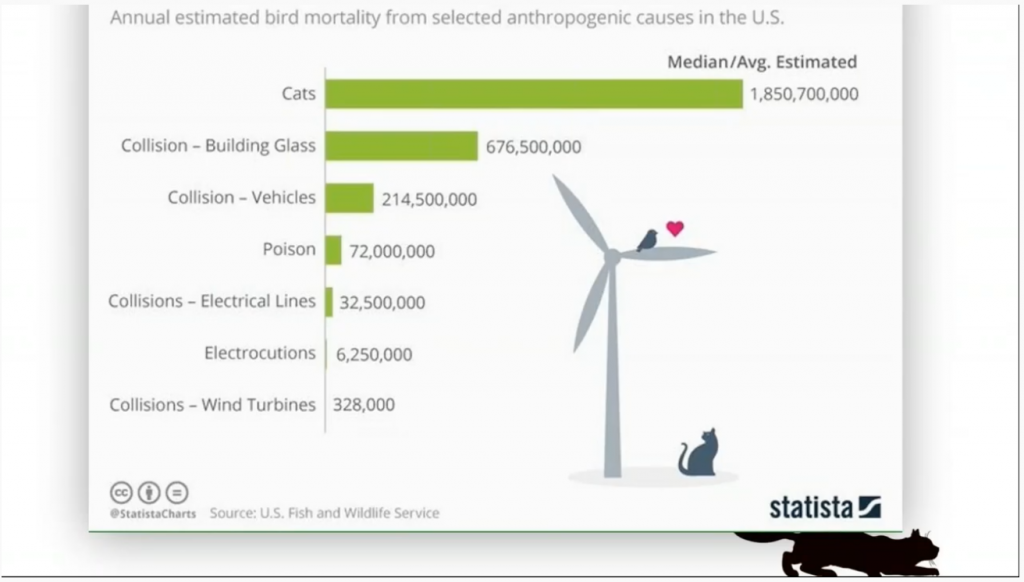

In the United States alone, cats kill billions of mammals and birds every year – much more than are killed by human-related causes such as wind turbines, power lines, and automobile collisions. A global study released in March 2020 found that pet cats kill between 4-10 times more wildlife per hectare than comparable native predator species.

“So forget that line that you often hear that pet cats are just playing the same role in the ecosystem that would otherwise be played by natural, native predators,” Trouwborst said.

The negative impact of domestic and feral cats goes beyond just killing. Other damaging effects include:

- Disturbance or fear effects – for example, one study showed that briefly placing a taxidermied cat near a blackbird nest reduced subsequent feeding of their young by 1/3;

- Competition – cats compete with other wild animals such as owls for small prey;

- Disease – cats introduce rabies, feline leukemia and other diseases to native wildlife; and

- Hybridization – cats mate with some wild species of cats, thereby affecting the gene pool.

What are the possible remedies? There are a few, but each has its own shortcomings.

- Sterilization – It can stop cats from reproducing but does not halt many of their other damaging effects listed above;

- Fit cats with bells, brightly-colored bibs, etc. – Those may alert adult birds and mammals to a cat’s presence but are less effective on baby birds and mammals; and

- Cat-proof fencing – It can be effective in protecting specific areas inhabited by vulnerable native wildlife, but it can also be expensive, impractical at a large scale, and still has a high failure rate.

The only thing that really works is simply keeping cats indoors at all times, Trouwborst explained. This has added advantages that pet cats won’t get diseases, be hit by a car, attacked by a coyote, or face other such risks when roaming free.

How do international wildlife laws address the issue? That’s what Trouwborst and his colleagues set out to learn. They quickly realized that laws are often unequally applied when it comes to cats. In the Netherlands, for example, the Egyptian goose is considered an invasive species and subject to eradication, but the feral cat may not be killed. A human must have a hunting license to kill certain birds, but there are no such restrictions against that same human’s pet cat killing said birds.

Trouwborst explained that dozens of international legal instruments have some applicability to cats, and they fall into three main categories:

- Rules concerning invasive alien species – to prevent and control those that are harmful to native populations. Most such laws prevent the introduction of and/or control or eradication of those alien species that threaten ecosystems, habitats or other species.

- Rules concerning site protection – areas important to the conservation of specific species and protect them from damage or disturbance, including that caused by cats. Such obligations can be triggered when domestic cats pose a threat to any wildlife which the site in question is meant to protect.

- Rules concerning species protection – for example, Article 5 of the European Union’s Birds Directive prohibits the deliberate killing or capture of native birds by any method, the deliberate destruction of or damage to their nests or eggs, the taking of their eggs from the wild, and the deliberate disturbance of these birds during periods of breeding a rearing.

Trouwborst and his colleagues found that pet owners and decision makers have had no qualms about restricting essentially all other companion animals. Dogs, snakes, ferrets, etc. all must be under the owner’s control at all times. Yet cat owners are unwilling to restrict their pets, and government officials are unwilling to admit domestic cats are a problem, much less address it. Trouwborst and his colleagues hypothesized this reticence was motivated by fear of becoming unpopular with parts of their constituencies. They were proven right when they published their findings in November 2019 and February 2020.

The researchers gave one exclusive interview, and soon after the story circulated, their phones wouldn’t stop ringing. Local, national and international media and social media went crazy. Their published research papers got more online traffic than all other law literature published last year, including papers on gun laws.

Aggression, ridicule and dismissal out of hand were the primary reactions. They also received vicious criticism and even death threats. Government officials in the Netherlands and the EU completely dismissed the scientific findings and even went so far as to dub Trouwborst and his colleagues “lunatic pseudo-scientists.”

Despite the backlash, Trouwborst remains confident in the research and conclusions. It is difficult to tackle most drivers of biodiversity loss, such as habitat degradation, climate change, and unsustainable agriculture. By comparison, addressing the free ranging cat problem is easy, he said.

“This is low hanging fruit, and it’s a shame not to pick it.”

Trouwborst likens people who are used to being able to let their cats out with people who were accustomed to being able to smoke cigarettes indoors. The change in practice was an annoyance for smokers, but it required balancing the individual’s freedom with that of others and the greater good. Smoking indoors was banned because of increased knowledge of public health effects. Trouwborst argues similar restrictions should be placed on cats because we now know their devastating effect on biodiversity.

Post date: April 8, 2020

Media contact: Kate Bradshaw

[email protected] | 727-430-1580