‘Bat Man of Mexico’ says we have much to thank, little to blame, bats for

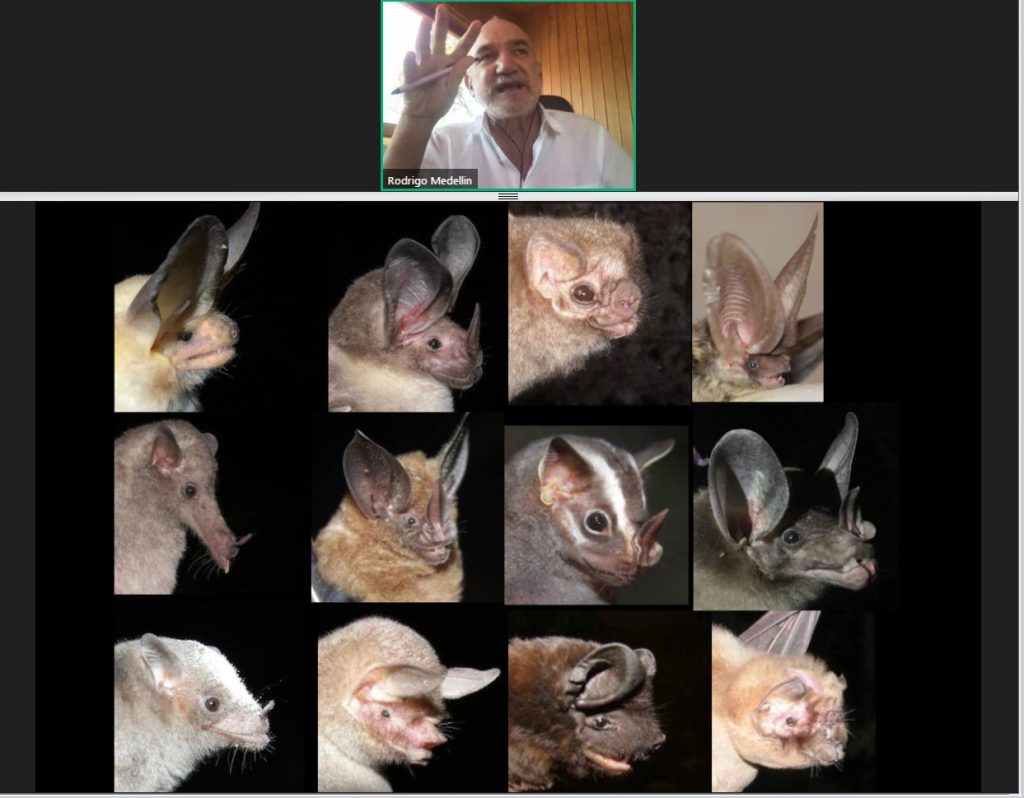

Stetson Law’s final Foreman Biodiversity Lecture for the 2020-2021 academic year featured Dr. Rodrigo A. Medellín, an ecologist, academic, and internationally renowned bat expert.

His lecture, “Bats and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Myths, Realities, and Hope in Pandemic Times” was an impassioned plea for the much-maligned mammals. For starters, he insists they are not ugly. And more importantly, they are not responsible for the most recent novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

Medellín knows bats get a bad rap, and “expert scientists” propagating fake ideas and blaming bats for spreading infectious diseases such as COVID-19 to humans does not help. One point Medellín drives home as often as he can to whomever will listen is that scientists and the media need to stop using the word “new.” Diseases or even species may be new to science but likely are not new to humanity or even Earth. In the case of emerging infectious diseases, it is more accurate to say these are “previously undescribed pathogens.”

Yes, humanity is seeing an increase in outbreaks of previously unknown diseases, including SARS, Ebola, Zika, Chikungunya and more. The headlines can be, understandably, frightening. Scientists still know very little about these viruses, where they come from, and how humans became infected with them. But scientists do know a few key things:

- Viruses are as old as life itself and are incredibly ubiquitous, abundant and diverse.

- Coronavirus are a family of about 300 species, and of those, only three can cause serious harm to humans.

- SARS-CoV-2 is a human virus that no animal, including bats, can transmit to humans.

- The bat SL-CoV coronavirus has a 96 percent similarity to SARS-CoV-2, but even if it entered human bodies, it would be unable to enter human cells and cause infection.

- There is no demonstrated evidence that SARS-CoV-2 jumped from bats to humans.

It’s important to bear in mind a new virus itself is just one piece of the puzzle. Without the ecological context, we cannot fully understand zoonotic (meaning those that spread between animals and humans) diseases. Killing animals believed to be the source of a “new disease” merely treats the symptoms, not the source of the problem, Medellín said. Another fact to consider: bats do not have more zoonotic diseases than other animals. In terms of proportion, song birds and rodents carry a higher number.

Humans are encroaching further into remote, pristine, previously unexplored areas of the world. The resulting loss of habitat and biodiversity, along with exotic invasive species spreading around the globe, has exposed us to new potential pathogens. There will undoubtedly be more diseases, Medellín said, but the first line of defense against the next pandemic is ecosystem and biodiversity conservation.

In addition to conservation, Medellín also points to a need to regulate and reduce the illegal, unsustainable consumption of bushmeat, as well as reducing global meat consumption and changing the forms of production of the animals we do eat. Crowded, unsanitary conditions in both wet markets and mass production farms create the perfect breeding ground for disease.

Many of our daily choices – from the food we consume to the products we buy – can have a ripple effect on biodiversity and, ultimately, human health.

“We all have something to do to prevent the next pandemic.”

Post date: March 30, 2021

Media contact: Kate Bradshaw

[email protected] | 727-430-1580