When the Arts Became Part of the Soviet State

Even someone with no background in Soviet history or theater would have been intrigued by Mayhill C. Fowler’s talk at the Homer and Dolly Hand Art Center – and not just because the history professor’s new book fit in well with the college’s wider centennial celebration of the Russian Revolution.

But the panel discussion with fellow Stetson professors – musicologist Daniil Zavlunov and art historian Katya Kudryavtseva – and questions that followed Fowler’s discussion on Thursday night, Oct. 5, showed a deep appreciation for her topic.

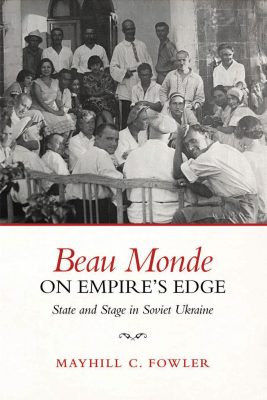

Fowler first explored it in her doctoral dissertation at Princeton, and expanded it into “Beau Monde at Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine,” a wide-ranging look at the intersection of theater and politics in the 1920s and 1930s.

“Fascinating,” said Robert Matyskiel II, a Stetson junior and history major who has taken two courses with Fowler. “This was ‘cultural credit’ for me, but I’m interested in her field and in film, so I really enjoyed this.”

So did Tonya Curran, and not just because Fowler’s discussion of the Soviet attempt to create culture in its far-flung regions after the Revolution. The Hand Art Center director also appreciated the interest it generated in the Stetson community – both faculty and students – and in the wider world.

Through Oct. 14, the Hand Art Center will exhibit “Tradition and Innovation in Russian Art,” which marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in 2017 and focuses on its impact on modern art.

“I was really engaged in Mayhill’s topic,” Curran said. “It was very broad but I felt that she, along with Katya and Danil – made it interesting, and the questions following their presentation were great.”

“Beau Monde,” Fowler’s first book, has been praised for its scholarship and also for its creative, energetic approach to a multi-disciplinary topic. “”Beau Monde at Empire’s Edge is a wonderful piece of work; it is beautifully written, in a witty, textured, and lively prose,” noted Irena Makaryk, a member of the University of Ottawa’s English Department.

“Beau Monde,” Fowler’s first book, has been praised for its scholarship and also for its creative, energetic approach to a multi-disciplinary topic. “”Beau Monde at Empire’s Edge is a wonderful piece of work; it is beautifully written, in a witty, textured, and lively prose,” noted Irena Makaryk, a member of the University of Ottawa’s English Department.

“Mayhill C. Fowler has a visceral – as well as an intellectual and theoretical – understanding of theatre and of audience that shows on every page of the manuscript,” Makaryk wrote.

That’s because her background is not only in academic history. Fowler, a Berkeley native who followed her bachelor’s degree at Yale University with a master’s degree in Fine Arts from the National Theater Conservatory – performed as a professional actor in Florida in 2003. She moved to her current track soon afterward, earning her master’s and doctoral degrees at Princeton in 2007 and 2011. Among the doctoral committee professors who encouraged her, “Serhy Yekelchyk continues to inspire me to make the cultural history of Ukraine comparative, theoretical, and a good read,” Fowler wrote in her Author’s Acknowledgements.

Enamel on Gold Bowl, Gold over Silver with polychromed filigree enamel, 1910. On loan from the Gary R. Libby Charitable Trust for the Russian art exhibit at the Hand Art Center through Oct. 14.

And that is exactly what her Hand Art Center presentation revealed: that during a pivotal moment in Soviet history, the arts – with an emphasis on theater — became central to the state that was being shaped after the Revolution. “There was an embrace between officials and artists when the arts became part of the state but the question was, ‘can creativity occur on schedule?’” Fowler asked, after sketching in the backdrop of the era.

“The notion of a ‘Beau Monde’ elite as a concept might be jarring – it might conjure the image of artistic types sitting at a café at Montmartre sipping wine,” but that is not the area she explored. “I was interested in the challenge of creating Soviet entertainment, when officials and artists grappled with the question of ‘how do we create entertainment for the streets,’ and how artists became ‘official artists,’” she said.

“My book does not end in the Kremlin but in the afterlife of these artists,” she said, pointing to their previously overlooked legacy – and to her future areas of interest and scholarship. “In a world in which they lived and worked has disappeared, I hope my book restores their context.”

— Laura Stewart