Sharing Their Stories

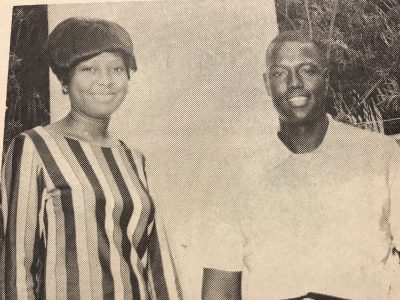

Jim Johnson welcomed Stetson students to the annual Multicultural Alumni Networking Lunch on campus last fall, as he reminisced and joked with his old classmates.

Johnson, Maurice Woodard and Franklin Biggins enrolled at Stetson in the fall of 1964, three of six African American men in the incoming class. They were not the first to integrate Stetson – that had happened with a few “test students” in 1962, when Stetson became one of the first private universities in Florida to admit Black students.

But the six freshmen who arrived in 1964 would be the first to live in the residence halls, eat meals in the cafeteria and experience campus life like other undergraduates.

After graduating in 1968, Johnson went to work for IBM and eventually retired as a corporate sales executive. Woodard retired as a dentist; Biggins, as a judge. Another classmate retired as a vascular surgeon. These are impressive accomplishments for any student, and more so for these six, who were pioneers of their time. As any historian will tell you, at that time Black students experienced significant challenges in pursuit of higher education.

Across the South in the 1950s and ’60s, protesters marched against segregation and staged sit-ins at “whites only” lunch counters. They were often beaten by angry mobs, attacked by police dogs and doused with water from firehoses – images carried by the national news that galvanized public support for integration. Weeks after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington in 1963, a bomb exploded in a Birmingham, Alabama, church one Sunday morning and killed four young girls.

At Stetson in 1964, the African American students recalled seeing a racist banner in a fraternity during Greek Week that prohibited Blacks, Hispanics and Jews. Once or twice, drunken fraternity members would call out racist names.

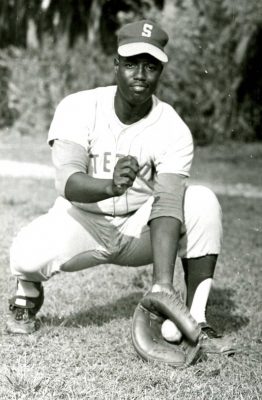

Johnson, the first African American on Stetson’s baseball team, spotted a substance like liquid heat in his jock strap in his locker one day. When the team trainer saw it, he started yelling at the white players, threatening to hit them with a baseball bat if they ever did it again. No one did.

Most of all, the new students felt isolated and unwelcome on campus, they said. Stetson opened the door for African Americans, but their path was not easy and, as a consequence, some did not return to the campus for decades.

“When I graduated in 1968, I did not step back on this campus until 1999, maybe 2000-and-something,” said Woodard, “… because I didn’t enjoy the environment. But it polished me.”

“Stetson helped to develop us to be in a position to take advantage of opportunities,” said Johnson, who credits the university for helping his career success, including serving in ROTC at Stetson and later as an officer in the U.S. Army. “I learned so much at Stetson.”

For Johnson, organizing the Multicultural Alumni Networking event is a way to give back to Stetson and students. “I found over the years that you have to be steeped in your faith, you have to have someone who’s pushing and encouraging, and you have to have people who are supportive, and I had all of that,” he said.

‘Detoured’ to Stetson

The son of fern workers in DeLeon Springs, Johnson was a top student throughout school and graduated as valedictorian of his class at the segregated all-Black Euclid High School in DeLand.

“My mother kept saying she was going to beat it into us to get an education because she didn’t want us to be where she was, working in the fields, standing on her head every day,” he said. “To explain that, she worked right next to my father in the fernery. They cut fern and, you may not know it, but the fern grows about 12 inches high, and when you cut it, you cut it about a half inch from the ground, so you bend over and that’s the concept of standing on their head all day.”

His parents were his role models. But they couldn’t afford to send him and his younger sister to college, so he excelled at sports, becoming captain of the football team and earning a partial football scholarship to Florida A&M. Then, near the end of his senior year in high school, he “got detoured to Stetson,” as he put it.

His guidance counselor George R. Williams called him to the office and asked if he would be interested in attending Stetson. Johnson said yes, if Stetson offered him a full scholarship.

“I went to see Admissions and Financial Aid, and lo and behold, they offered a full scholarship,” Johnson recalled. “Now some of that, of course, was work study and some was a loan. … It wasn’t like it was all grant, but it didn’t matter. I was able to go to school and I knew that I could have it for four years.”

Johnson wanted to major in math, but according to his high school transcript, he hadn’t taken trigonometry and calculus. Johnson explained those classes weren’t offered at the Black high school, so Stetson’s dean of the math department lined up a student to tutor him over the summer.

On the first day, the tutor asked questions to assess his knowledge. She expressed surprise because Johnson knew the basics of advanced math, including calculus. His high school math teacher, Earl McCrary, had taken him and five other students aside and taught them advanced math, without ever using words like “calculus.” “He knew these six kids would probably go to college,” Johnson explained. And they did.

The Forest of Arden

When Johnson first met Stetson President J. Ollie Edmunds, the president said he would like to learn more about Johnson’s background. The president suggested they take a walk and so began a series of walks for the two in the Forest of Arden, a wooded area near Sampson Hall, where the Homer and Dolly Hand Art Center stands today.

During the summer of 1964 and into the fall, the two discussed desegregation and what it meant for Stetson and African American students, like Johnson.

The Stetson faculty had favored desegregation in 1951, years before the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled in 1954 that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

In 1955, the executive council of the Baptist Student Union voted in support of integration, but a campus-wide vote by the student body defeated the idea, according to newspaper articles from the time. Instead, President Edmunds and Dean William Hugh McEniry, a longstanding advocate for racial integration, quietly worked to enroll a black student.

Cornelius “Neil” Hunter, a top student from Starke, Florida, became Stetson’s first African American full-time student in August 1962. He was joined by Herdie Baisden, the first part-time African American (commuter) student, according to records in Stetson’s archives.

“I spent a lot of time talking to Dr. J. Ollie Edmunds the summer before actually starting school, walking through the Forest of Arden and he explained that Neil was an experiment and he was happy that he was passing, and because of that, I’m here,” Johnson remembered. “He said, ‘you six guys’ – and that was the first time I realized I wasn’t the only one and I was glad – he said ‘you six guys coming in this year will be the first to live on campus. You’ll be the first to eat in the cafeteria on a regular basis.’

“Neil lived with a professor, and it was a professor in his major. And it’s not that they gave him anything, but he had someone to talk to and a support person, where we would be on campus like all the other students living in the dorms, and like any other student leaving home, you’re kind of on your own.”

But Johnson wasn’t worried. “I had faith in God. I believed I could do it. There was a quote by St. Francis of Assisi that I always remember. He said: ‘Do the necessary, do the possible and you’ll find yourself doing the impossible.’”

-Cory Lancaster

-Videos by Bobby Fishbough

Read Part Two: Walking in the Forest of Arden

Stetson’s first African American students recall some of the challenges of the ’60s