Artist’s sketch provides insights into legacy of Bluemner

Museum visitors are given the opportunity to view masterpieces by artists working at the height of their ability. Typically these artworks are accompanied by a label or catalog that provides some context about the artwork or the artist’s life. And while this method provides a lot of information, the viewer rarely gets glimpses of the artist’s processes.

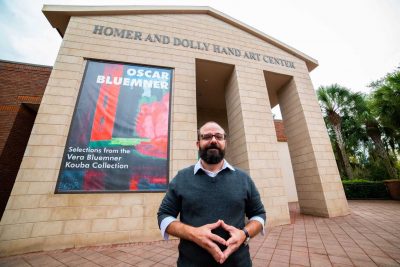

But in the case of Oscar Bluemner, the Hand Art Center can expand the viewer’s understanding of a particular artwork by studying its preliminary sketches. Stetson University’s collection of over 1,100 works by Oscar Bluemner, housed in the Hand Art Center, include many preliminary sketches and color tests for the completed artworks.

A sketch is not necessarily a blueprint for an artwork. The sketch allows for an artist to compose an image with broad strokes, it allows them to experiment with composition, proportion, form and even color. The sketch can record important components of the scene while the artist is on-site and then allow the artist to experiment and dial-in what works in a composition and eliminate what does not when they return to the studio.

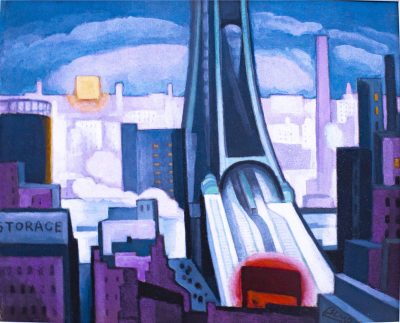

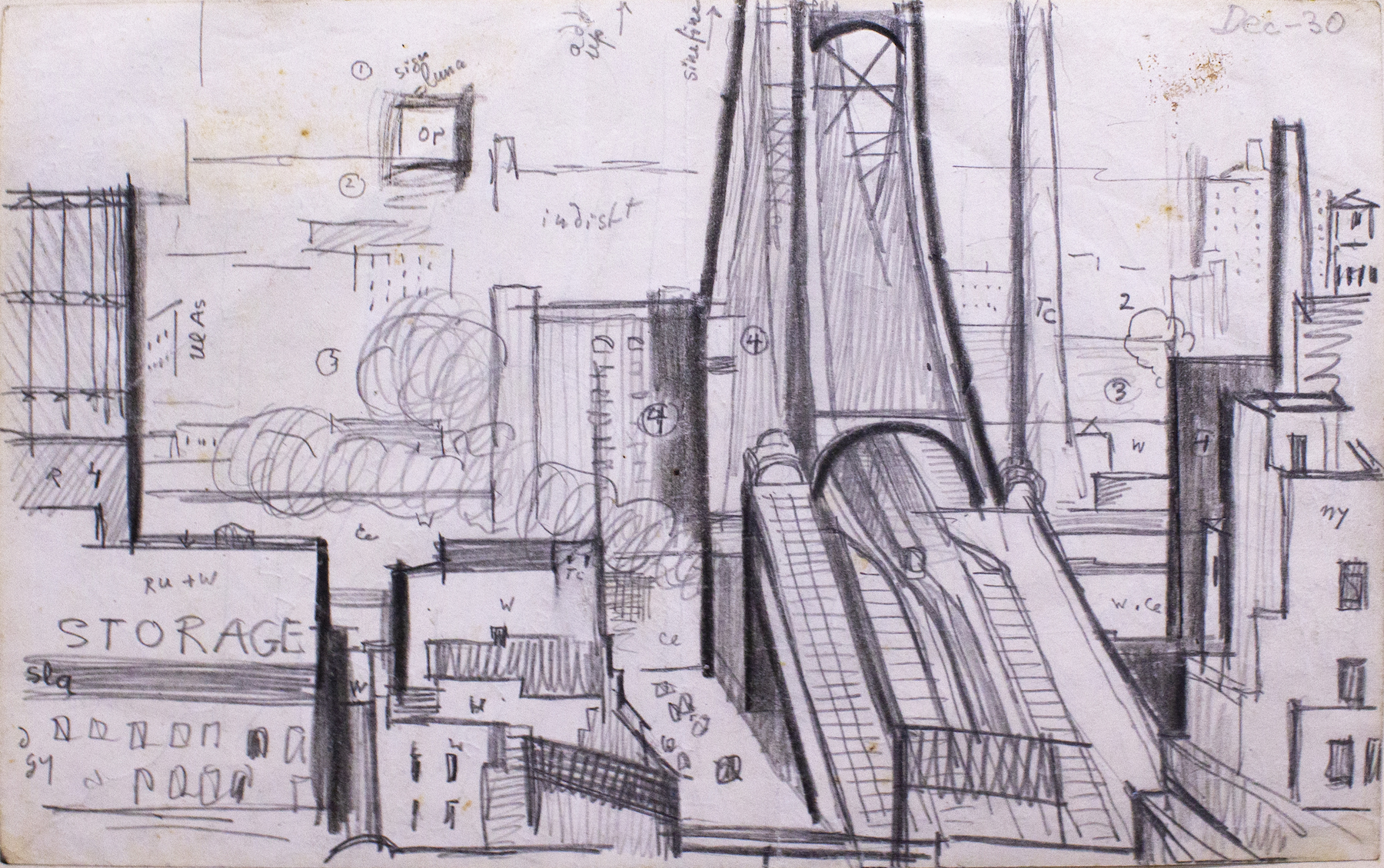

Two pieces from the Hand Art Center’s collection of Bluemner’s artwork provide the perfect example: A preliminary sketch in charcoal and its corresponding finished piece in watercolor titled “Bridge” from 1931. Viewing both of these pieces together shows how Bluemner was working through the sketch to achieve in the final piece the results he was aiming for. This sketch in particular shows Bluemner on-site, recording as much information about the scene that he could with the use of numbers, letters, symbols and even brief notes for himself. By comparing the characters and symbols located on the sketch to their corresponding locations on the completed piece, it seems as if Bluemner was creating categories of color, and possibly distinguishing between intensities of color. There are also a few instances where letters are combined which could show Bluemner attempting to mix colors with his eyes.

Beyond the use of letters and numbers that correspond to color and intensity of color, the very lines of the drawing itself create a subtle language that informs Bluemner’s process.

Bluemner was initially very interested in architecture, and that is evident in how he rendered this cityscape. Overall the drawing of the architecture is very precise, but he is also concerned with the space between and around the buildings. He includes the pluming smoke to the left of the bridge that creates a sense of distance between the buildings in the foreground and those in the background. This little element, sketched with a twirling circular line — the way a child would draw a cloud— gives the finished composition depth and is a key component in the painting’s success.

Bluemner’s use of lines in the sketch are also a type of code for the final piece. The intensity of line, its dark or light quality, relates to the intensity of color. It seems that the darker lines indicate the darkest blues, and the darkest lines aided by crosshatching refer to shadow or the lack of color and light altogether.

This sketch technique is a type of coded language, and importantly it is one that can help distinguish artists from the early 20th centuries from their contemporary counterparts. Many contemporary artists will work from photographs, capturing the sketch of a scene with the click of a shutter. However, Bluemner and the painters working before modern camera technology could rely only on their eyes. And there is a kind of magic in a scene that cannot be fully captured by a camera, but can be thoroughly processed by the mind’s visual cortex. The human mind’s ability to remember and calibrate white balance against the full spectrum of visible light allows for subtle variations in hue and intensity between small sections of a composition.

Unlike a snapshot of a cityscape, captured by even the most advanced digital camera, the human eye can account for variation within variation. The challenge for the artist is not in noticing this variation as much as it is in recording and keeping the mind’s snapshot organized long enough to reproduce it on canvass. The sketch, in this way, is a codified language designed to remind the brain of a scene’s variations on shape, color and intensity. Through Bluemner’s sketches, the viewer has a stronger sense of his ability, and more precise understanding of his working process.

“The Bridge” can be seen in the current Bluemner exhibition at the Hand Art Center. The exhibition, including a cultural credit opportunity, can also be viewed on the Hand Art Center website: www.HandArtCenter.org.

-James Pearson,

Director, Hand Art Center