Homeless Evangelist

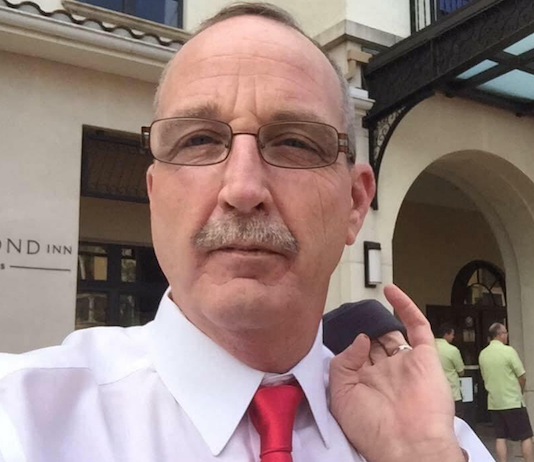

Until 2014,Tom Rebman ’10 ’11 had “absolutely nothing” to do with homelessness, he said.

Today, Rebman is an expert on the topic whose counsel is sought by municipal leaders from near and far throughout the nation.

What a difference six years make, particularly the one year spent homeless, from August 2015 to August 2016, starting in Orlando and continuing in 13 other cities.

In the beginning, all Rebman wanted to do was ensure his young students would read during the summer. With a bachelor’s degree in education and a master’s in reading, he taught reading, grades six through eight, at economically challenged Lockhart Middle School in Orlando. At the time, his wife was in charge of all food pantries for Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, which led to his introduction to homelessness.

Then he quickly got immersed.

“I said to myself, ‘That’s a great idea. What I’ll do is over the summer I’ll go homeless,” he remembered. “I thought I could teach them [the students] empathy for the homeless, and they could read my posts and respond to them.”

And so, in the summer of 2015 at Orlando’s iconic Lake Eola, Rebman kissed his wife and walked away with no money and nothing in his pockets except an ID. He spent 30 days on the streets of The City Beautiful.

During the subsequent 11 months, with sporadic assistance from his wife, he was voluntarily homeless for nearly 100 days, living in Palm Bay, Tallahassee and other Florida cities, and in Los Angeles.

His experiences were documented on Facebook. Additionally, you can see for yourself with a brief search on YouTube, where his trials and tribulations, along with his outspoken beliefs on homelessness, are easy to find.

‘What I Found’

That first month in Orlando was a real eye-opener, said Rebman, who arrived at Stetson as a retired Navy lieutenant and business executive.

He learned that at a cost of $10 nightly he could sleep in a shelter. Also, he had no idea there were so few programs to keep him off the streets, and those that were available were so punitive “he would rather sleep on street than stay there.”

“What I found out during my first 30 days is there’s no help for homeless people,” he added.

As part of his exploration, according to Rebman, he sold plasma, ate at soup kitchens and did day-labor jobs. Further, he applied for 139 jobs during those 30 days in Orlando, falsifying his resume in only one place — to write “homeless” in the address block. He even included his two Stetson degrees.

“I didn’t even get one interview. … I found out that homeless people really don’t have help. And that’s why I got so engaged,” he said.

“I’m trying to break the myths of homelessness. So, here I am. I don’t drink; I’m not a drug addict. I’m homeless in Orlando. For 30 days I apply for 139 jobs, and I can’t even get an interview. And we wonder why people get disgruntled and don’t want to look for work!”

He dug deeper, culminating his year of homelessness in the downtown Los Angeles neighborhood known as Skid Row, one of the nation’s most populous places for homeless people.

“The homeless service industry has become a profit center instead of serving people,” he emphasized.

All the while, Rebman researched, talking to the homeless, not as an outsider but as one of them. He interviewed more than 150 homeless people. “They didn’t think they were talking to any agency; they thought they were talking to a peer,” he noted.

Largely, those people composed three demographic groups: 1. The mentally ill, who often cycle from jail to hospital to the streets. 2. The physically disabled who can’t find medical aid. 3. People who are episodically homeless, with something catastrophic happening in their life, leaving them unable to rebound without the availability of needed help systems.

Consequently, Rebman said, the severely addicted homeless person who often is the most visible represents about 15 percent of entire homeless population, while “the other 85 percent are people really in need. And that’s what the public doesn’t know.”

‘Just Doing What I Love’

Now, Rebman is working to change those circumstances. In 2017, he began spending his summers meeting with community service providers and advising cities on how to solve homelessness. This summer he was in South Bend, Indiana (home of the University of Notre Dame), helping city officials.

In Florida, he has addressed a governor’s council on homelessness, detailing his personal journey on the streets. He has worked with state Rep. Randy Fine and Florida Congressman Bill Posey on policy development.

In Palm Bay, where he now lives — and teaches at Odyssey Charter School — he has led community workshops; established the city’s first cold-night shelter; helped to create a community referral and resource center; helped to deliver a reunion and transportation fund designed to enable homeless citizens to be reunited with loved ones; and founded the Homeless & Hungry advocacy group to change “the state of homelessness.”

And notably, Rebman asserted, he refuses to receive any financial compensation for his efforts, other than for expenses.

“As soon as you start charging [municipalities], you can’t really tell the truth,” he explained. “Nobody can say that when I come into a city, I have any interest except the truth. Here’s the real truth: The system is broken throughout the United States.”

Finally, Rebman insists he’s not volunteering. Instead, he said, “I’m just doing what I love to do.”

Rebman even has heard the term “homeless evangelist” used to describe him. His response: “I say they’re right.”