Acoustic Ecology Panel Kicks Off International Conference On Soundscape Studies

When Jacek Smolicki was named artist-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts’ Soundscape Field Station at Canaveral National Seashore, “I was imagining that I would be in the middle of this pure, amazing and pristine soundscape,” the Polish-born artist, researcher and educator said at a panel discussion on “acoustic ecology” held Wednesday, March 22, in Rinker Auditorium at the Lynn Business Center.

“But there’s still a lot of air traffic, there’s motor boat traffic,” Smolicki said. “Anthropogenic noises, which are the noises generated by humans, are still the dominant ones, even though you are in the middle of the park.”

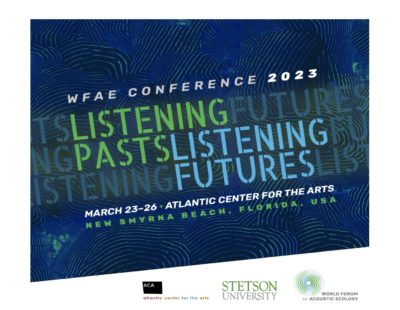

Acoustic ecology, also called soundscape studies, is the multi-disciplinary study of the social, cultural and ecological aspects of sonic environments across the world, according to the website of the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology. The panel discussion was the kickoff event for “Listening Pasts – Listening Futures,” the WFAE conference that runs March 23-26, at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach.

“Acoustic ecology really affects us at an almost biological level,” Smolicki said. “The way we respond to sounds that surround us is how we coexist. People are trained primarily to perceive space through visual means, but what if we started seriously considering all the sounds that surround us? Then we would realize that we actually live in quite a cacophonous environment with a lot of noises affecting us. Acoustic ecology can contribute to the broader discussion about environmental, societal and political transformations that we need to basically save our planet.”

Since the WFAE was founded 30 years ago in Canada, this weekend’s event marks the first time an international conference on environmental sound studies is being held in the United States. Stetson is one of the presenting partners for the conference.

The theme for the panel discussion was “What can listening teach us in a world of crisis?” Moderated by Nathan Wolek, PhD, professor of Digital Arts and Music Technology, the panel featured writer/biologist David George Haskell, a Guggenheim Fellow and professor at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn.; sound/performance artist Amanda Gutiérrez, currently pursuing her PhD at Concordia University in Canada; Canadian-born composer/artist/clarinetist/podcaster Claude Schryer, a founding member of the WFAE; and Smolicki, currently a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at Harvard.

Haskell, Gutiérrez and Schryer are the three keynote speakers at the ACA conference.

As the panel discussion made clear, acoustic ecology is about more than noise pollution and acoustical engineering.

Gutiérrez cited the “political and social dimensions of acoustic ecology” and noted her doctoral studies are focusing on research and interdisciplinary practices “in sound and feminism,” including how “sound can be potentially a space for women” and for those identifying as “non-binary, queer and lesbian. Sound can be a space for creation, a space for dialogue, a space of co-listening.”

“How do we relate to sound is what is most important to me,” Schryer said. “How do we relate to sound, how does sound inform our lives and how do we have a good relationship with the sounds around us. There are so many living beings that are not human who are making sounds and trying to communicate to each other and us.”

In passing, Schyer cited composer John Cage, who was famous – some say notorious − for his 1952 work titled “4′33.” Its live performance consisted of Cage strolling onto a venue’s stage, opening the cover of his piano’s keys, and sitting silently for four minutes and 33 seconds. Cage’s point was that any ambient noise that traveled to the ears of the audience – a listener’s cough, a diesel truck thundering by outside the concert hall, etc. – became the “music” of the piece.

Smolicki, a native of Kraków, noted that in 2013 he composed a “soundwalk composition” for that city’s annual commemorative march from the city’s former Jewish ghetto to the nearby site of Plaszow, the infamous Nazi concentration camp.

The goal “was not so much to re-enact or re-create the soundscape of the past, but to re-create conditions so people could imagine how those places might have sounded in the past,” Smolicki said.

“Sound inherently connects one being to another,” said Haskell, whose acclaimed new book is “Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction.” “We are living beings connecting through sounds. The birds and the trees or the insects singing are connecting to one another. When a star explodes, there are sound waves that come through. Or when a rocket takes off down the road here, there are sound waves. The rocket is not as we traditionally understand it a living being, but there is still connection happening there. So, sound unifies and connects.”

The panel discussion was attended by some 40 people including Noel Painter, PhD, Executive Vice President and Provost, Professor of Music and Elizabeth Skomp, PhD, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, who introduced the program. Skomp noted the event was made possible through support from Stetson’s James Turner Butler Creative Lectureship.

Eve Payor, community arts director at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, introduced the individual panelists.

– Rick de Yampert