Celebrating 140 Years: 1913-1922, Decade of Ringing Resilience

1915

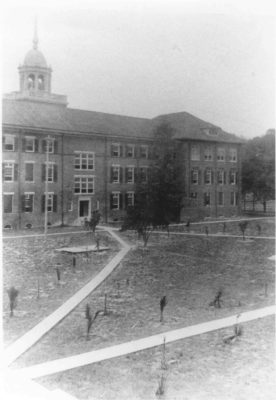

Eleven rough cast bells — later to become the Eloise Chimes — arrived on campus, but not in a way one would expect. The bells, delivered to the front of Elizabeth Hall, were the result of a canceled order in Pennsylvania. Stetson, ever resourceful, seized the opportunity to bring the chimes to campus.

The bronze bells were quite measurable — ranging in size from 575 to 3,000 pounds. Yet, as it turned out, their historical significance to the university was even weightier.

Originally, the bells were housed in the cupola of Elizabeth Hall, hung from a structure that was 106 feet high. After many years, however, that structure began to succumb to the sheer weight of the bells and continual vibrations of the chimes. As a result, the bells were removed and were without a home until the construction of Hulley Tower in 1934, where they resided until 2005.

Hulley Tower was named for Lincoln Hulley, Stetson’s second president (serving 1904-1934). In turn, the bells were renamed the Eloise Chimes to honor the president’s wife, Eloise. That new location in the 116-foot Hulley Tower allowed for the bells to be played, with the chimes’ peals heard daily across campus.

Hulley Tower originally also contained a mausoleum for President Hulley and wife Eloise. He and his family had built the tower as a gift to the university, but the president died before it was finished. Then, in 2005, with the university citing safety concerns, the upper part of Hulley Tower was dismantled, leaving only the mausoleum intact.

Through the years, the 11 bells were salvaged. Some were donated to community organizations. Others were installed at various campus (east side of Hulley Mausoleum, first floor of duPont-Ball Library, rear patio Meadows Alumni House and side yard of President’s House).

Today, fittingly, university efforts are underway to further celebrate the past with a restoration of Hulley Tower to, in many ways, symbolize both resilience and rebirth on campus.

1918

Stetson’s experience with the COVID-19 pandemic actually had a predecessor — the H1N1 virus pandemic, commonly known as the Spanish flu of 1918. Globally, the Spanish flu claimed more than 50 million lives, including approximately 675,000 deaths in the United States from 1918 to 1920. Florida lost more than 4,100 residents, and 75 people died in Volusia County in 1918 alone.

As Stetson opened fall 1918 classes, the pandemic appeared on campus for the first time. Approximately 150 students got the disease (out of 459 regular students). Two students died, with a few others later dying after returning home.

In the end, the university, in what would foreshadow efforts of more than 100 years later, rallied to ensure continued vitality. In September 1918, the U.S. government contracted with Stetson to house, train and educate young men who were waiting to be sent to World War I. Those students were part of the Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.), a national effort that placed male students in colleges for war training and studies. Stetson, one of four Florida colleges granted the S.A.T.C. designation, eagerly sought S.A.T.C. students, as they brought with them government funding that helped improve the university’s financial health. The plan worked, with Stetson University, as a whole, steadily recovering.

Learn more about Stetson’s 140-year anniversary and join in on the celebration throughout the fall.

-Michael Candelaria and Stetson University Archives