‘The Artist’s Labor’ of Love at Hand Art Center

Photo by Rick de Yampert

Several years ago, Katya Kudryavtseva, PhD, associate professor of Art History, noticed something peculiar — and unsettling — about one of her new students, Mario Saponaro ’23.

“The first thing I noticed about him was he would always be sketching, sketching, sketching,” says Kudryavtseva, who also is the Vera Bluemner Kouba curator for Stetson’s Hand Art Center.

“I would be extremely annoyed by that, because here I am bestowing wisdom, right?” she adds with a chuckle. “And he is like, ‘do, do, do’ (she imitates a drawing motion). With time, I actually learned to appreciate this unwavering focus. It’s very rare in people.”

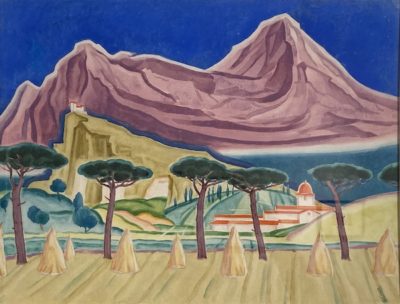

Kudryavtseva also came to appreciate Saponaro’s art, so much that she invited Saponaro, who graduated with a double major in Studio Art and Art History, and a minor in Music Performance – Piano, to be part of a Hand Art Center exhibition featuring the works of Modernist painter Oscar Bluemner.

The German-born Bluemner (1867-1938), who emigrated to the United States in 1892, is now known as a key, acclaimed American Modernist. And Stetson is a key player in Bluemner’s legacy: The Hand Art Center is home to more than 1,000 Bluemner creations bequeathed by daughter Vera Bluemner Kouba to the university in 1997.

The Hand, as it’s sometimes called, features two Bluemner exhibitions each year, curated mostly by Kudryavtseva but also by an occasional guest curator. The current exhibition, “The Artist’s Labor: Oscar Bluemner and Mario Saponaro, showcases the Modernist’s landscapes and architectural works. Also, it features Saponaro’s “Home Maintenance Mandatory Series, with its comic book-like “goblins.”

Kudryavtseva and Saponaro will present an artist and curator talk on Wednesday, Oct. 25, at 6 p.m. Cultural Credit is available.

Pairing the Legend and the Learner

Kudryavtseva cites a number of motivations for the Bluemner-Saponaro pairing.

“At first glance, this pairing might appear unconventional: Bluemner’s landscapes clash with Saponaro’s fantastical creatures,” Kudryavtseva writes in her curator’s statement that accompanies the artworks on the wall of the Hand. “Yet, a common thread binds these artists together — their profound dedication to their craft. The exhibition delves into the very core of the artistic process, illuminating the shared spirit of creativity and experimentation that drives them both.”

Indeed, ask Saponaro about his most memorable experiences at Stetson, both personal and artistic, and he doesn’t hesitate. “They kind of mixed together,” he says. “I spent a LOT of time in the studio, especially my senior year when I had a big project to do. That’s my favorite part — when I got my own space (in Sampson Hall), and I could stay there 24 hours if I wanted to. I spent nights sleeping in there.”

There were more motivations for Kudryavtseva to pair Bluemner and Saponaro.

“I wanted to make an exhibition that would make Stetson’s extraordinary Bluemner collection more relevant to contemporary students,” Kudryavtseva says. “We have to think about maintaining Bluemner’s legacy and keeping him relevant.”

Past Bluemner exhibitions were “intellectually engaging and visually too, but it always bothered me that students don’t see them,” she says. “You need to have a developed habit of going to museums, of going to galleries. And you know what? Our students don’t have such developed habits. This is not me trying to be snobbish. That’s just the fact.”

Kudryavtseva seeks to change that fact.

“I thought it would be interesting to mix it up a bit,” she explains. “Mario is an alum. He exemplifies the best qualities of Stetson. … Mario is a real deal. Becoming a famous artist is always a lottery, but he really has a chance.”

Kudryavtseva also sees “important parallels” between the acclaimed Modernist and her former student, especially in each artist’s process.

“One of the first things people notice about Bluemner is how maniacal he is about the process,” Kudryavtseva describes. “Bluemner’s process is very complicated. This is what gave me the idea about Mario, because he has this unwavering focus. That is quite rare. He has this awareness and self-reflexivity about the process.”

Along with finished artworks by Bluemner and Saponaro, “The Artist’s Labor” includes a number of “preparatory sketches” by Saponaro, as well as a 10-minute documentary, made by Stetson Digital Arts major Dominic Addonizio and looped on a giant video screen, in which Saponaro talks about his process.

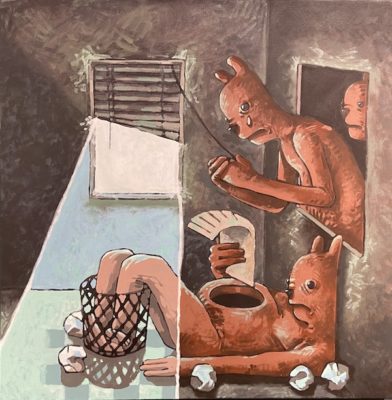

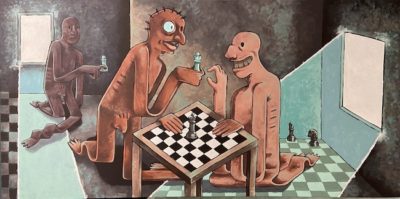

How did that process lead to the creation of Saponaro’s “goblins” — those fantastical, now-whimsical, now-wistful creatures that he variously labels the “flat guy,” the “bunny” and the “fish”? (There’s an upright-walking chameleon in the mix, too.)

“The foundation is actually very real; it was those objects,” Saponaro says, referring to his exhibition’s pencil drawings, which realistically depict a chess piece, a crumpled piece of paper, an egg and a hat.

The Bizarro

So, how did the leap occur from those everyday objects to his bizarro creatures?

“Logistically, the flat guy does not make any sense with the chess piece, and the bunny doesn’t really connect with the scrap paper,” Saponaro confesses. “It’s not necessarily a one-to-one. I guess it’s a journey.”

The term “goblins” to denote his creatures came from Kudryavtseva, Saponaro says. “I do love my goblins, I love to do the creatures,” he says. “I love dark shadows, scary things. I like horror movies, but I don’t really watch too many of them. I can do still life and I do portraits sometimes now. But really the goblins are where my passion is.”

Saponaro, who now lives in Jacksonville, grew up in Palm Coast in an artistic family. Both parents are artists, his father (also named Mario) is a rock and blues guitarist who plays frequently in the Daytona Beach area, and his sister also is a musician.

“It was the whole shebang — music and art almost everywhere,” Saponaro says.

He recalls as a child proclaiming he wanted to be a doctor — “But I think that was a lie because I can’t remember a time where I’ve ever wanted to be a doctor instead of an artist.”

Supported by his family in his artistic pursuits, Saponaro began taking advanced art classes in the seventh grade and continued into high school, but he balked at studying art in college.

“It was like, ‘Mom and Dad, if I can figure out how to do art, then I don’t want to go to college,’” he recalls. “Obviously, I did not figure out how to do it (rueful laughter).”

Saponaro applied to the Savannah College of Art and Design, as well as Stetson. SCAD offered him a scholarship, but Stetson offered him a better one — to study piano.

“So, it was a music scholarship that I turned into an art major,” he says, adding that the university didn’t feel he was pulling a bait and switch about music. “I always told them that I want to be an artist. Piano is always a pretty close second for me. Most of the way I make money now is from playing out, playing piano everywhere.”

Saponaro says Kudryavtseva “brought me knowledge of art and art history and made me able to kind of immerse myself in the art world, where before it was foreign to me. Now I feel more comfortable being able to think critically about things, both practically for my art and practically about moving forward in a career.”

Along with his family and Kudryavtseva, Saponaro points to his former teacher Luca Mulnar, MFA, assistant professor of Art, and his girlfriend, Lily Paternoster ’23, an Art History major, for being instrumental in his development as an artist.

While Saponaro says his goal is to be a full-time professional artist, ask him the proverbial “Where do you see yourself in five years?” and he says: “The answer is ‘I don’t know.’ I have ideas of where I could be or what could happen, but I just don’t know A, if it’s gonna happen, or B, how to make it happen.”

He does know one thing: “I can’t not make art. If I ever didn’t, I think I would explode into a million pieces. It’s an addiction.”

Note: Follow alumnus Mario Saponaro on Instagram at zestyarts.

– Rick de Yampert