Tragedy and Triumph

Editor’s note: This article appears in the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Stetson University Magazine, which will be in mailboxes soon and is now available online.

Mildred Cross Spalding was awestruck that January night in 1979 as she and 39 of her Stetson classmates took some free time to walk the streets of Innsbruck, Austria. The city was one of the stops during the business school’s trans-Europe, study abroad trip led by Edward Furlong, then-Dean of Stetson’s School of Business Administration, and Joe Master, revered professor of Accounting.

“It had snowed 3 feet, and it was like a picture postcard,” says Spalding, who was known as Mimi during her Stetson days. “It couldn’t have been a prettier night.”

The next day — Jan. 15, 1979 — many Hatters were excited to ski the slopes of 6,300-foot-high Seegrube Mountain near Innsbruck, but authorities closed the mountain due to an avalanche threat from the heavy snow. By late morning, however, the decision was made to open the slopes to skiers.

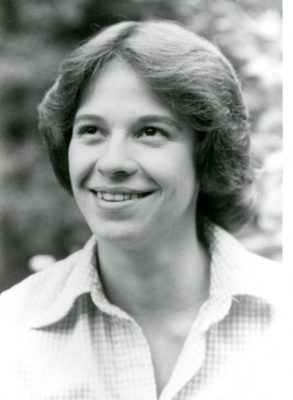

Jill Jinks ’79 “had never been on skis,” she describes. Despite being the star quarterback of the Tri Delta championship flag football team, she was relegated to the beginners’ area known as the “bunny slope,” even though that spot was unnervingly close to a ledge.

Standing on her skis, Jinks, like other Hatters, says she “heard absolutely no sound” during the moment she “looked up, and I watched the mountain come apart.”

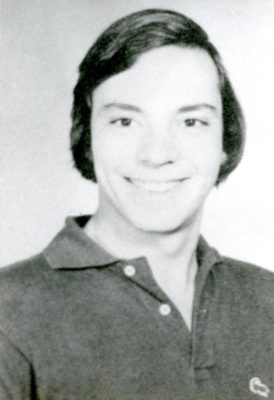

Stuart Pavlik ’79 recalls hearing something.

“People say when an avalanche breaks there’s no sound,” Pavlik says. “But in my mind I heard something. I’m still trying to ponder what that was.”

Spalding, who was on the slope standing “1 foot away” from classmate Katy Resnik, remembers the wall of fast-moving snow “looked to be three blocks away. Katy and I were looking at each other like, ’What are we supposed to do?’”

Spalding turned around and the snow “went straight over me on the backside and took my gloves off. Katy was swept into a drift under the ski lift.”

Spalding was buried under 3 feet of snow and ice. Resnik and other Hatters were submerged by the snow, too.

“I was panicky and hyperventilating,” Spalding says. “I was able to move just enough snow to get maybe an inch air pocket with my nose. I realized I can’t be panicky and hyperventilating or I’ll die in a minute. So, I had to go into low gear and just lay there. Prayed, thought about my loved ones, of course. It was super quiet. I thought I was going to die.”

Fifteen minutes later, she “heard the dogs, and I had hope I would get rescued,” she continues.

Professional rescue personnel and Austrian townspeople had been summoned to the mountain by the region’s numerous belltowers sounding their bells to form a rescue crew. Jinks and other Hatters not engulfed by the avalanche joined the rescuers, some 200 strong. Aided by dogs that could sniff humans’ scent, the rescuers formed a long line and slowly trudged side by side up the slope, poking long, thin poles into the snowdrifts, hoping to feel life.

As Jinks had watched the mountain come apart, “I recall thinking, ’I wonder what they are going to tell my dad because I’m about to die.’” The wall of snow and ice stopped just feet away.

But Jinks was untouched by the rampaging snow, and she became part of the rescue group that found classmate Hunt Parry: “Hunt was white like a sheet of paper. He looked up and said, ’Wow, I was just about to go to sleep’ — suffocate.”

After locating Spalding 15 minutes after the avalanche, rescuers needed another 15 minutes to extricate her.

“It was difficult to get me out because I was quite hysterical,” Spalding says. “I was the last one rescued alive.” She was crying and her hands were frostbitten, but otherwise she was unhurt.

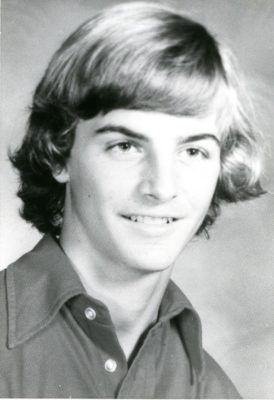

Stetson students Katy Resnik, Scotty Fenlon and Dennis Long were lost to their families, friends, classmates and the entire Stetson community that day.

The next day, “THREE U.S. STUDENTS KILLED IN AVALANCHE IN ALPS,” proclaimed the headline of a New York Times photo on Page A2.

“Katy stood 1 foot away from me during the avalanche and she died, and I lived,” says Spalding, an Atlanta resident and retired interior designer who works with nonprofit agencies. “I always think about ’How did that happen to her and not me?’”

The Aftermath … And Remembering 44 Years Later

Some Hatters decided to continue the study abroad trip. Others returned home immediately.

“Staying gave me time to process and heal versus hopping on a plane and going back to the U.S.,” says Susan Perry Brockway ’79, a Boca Raton resident, retired accountant, community volunteer and vice chair of Stetson’s Board of Trustees. “There was a lot of anger, especially with a lot of the guys. It was like ’How could this happen? Why?’”

Three funerals. A memorial service in the chapel of Elizabeth Hall, with the Eloise Chimes of Hulley Tower ringing across campus. And then …

“Your life goes on is the best way to say it,” Brockway says. At the time, there was preparing for graduation and for new careers.

Yet, across the ensuing decades, that fateful day “has been really heavy on my heart,” Brockway adds.

In early 2023, Brockway got a call from Jinks out of the blue. Jinks said, “I really want to do something; we need to do something.”

Brockway’s response: “Jill, you found the right person because it’s been heavy on my heart, too.”

It was time to remember — palpably, publicly.

Looking Back in Sadness, Looking Forward in Community

Jinks, a Stetson Trustee and insurance executive with a degree in finance and economics, and a doctorate in education from the University of Georgia, joined the faculty of Stetson’s Summer Innsbruck Program in 2022. Despite the location, the program, now in its 27th year, is not a direct descendant of the 1979 study abroad trip.

But that long-ago trip loomed large and heavy in Jinks’ heart as she shared her memories a few years ago with Innsbruck summer program co-director John Tichenor, PhD, associate professor of Management.

As Jinks recalls, “John was shaking his head going, ’Jill, we don’t know this; why don’t we know this?’

“People are shocked when I tell the story now. They go, ’Jill, I’m so sorry — I had no idea.’”

Jinks sought change. An Atlanta resident, she reached out to Rina Arroyo, chief of staff and senior Development officer, Office of the President. Arroyo was stunned to learn about the 1979 tragedy, and at one point she began crying as Jinks shared her story of Innsbruck — and how that horrific day had been largely put in the past, forgotten. Jinks asked for Arroyo’s help “to reach out to my friends and fellow students to ask them to do remembrances,” even though Jinks had little idea of how those remembrances might bear fruit.

“I was surprised that I had not heard about the 1979 Innsbruck tragedy — I had been at Stetson for nearly two decades and had not heard about the tragedy,” comments Arroyo. “The story had nearly been lost to time at Stetson. If you think about it, it was a different day and age back then … no cellphones, no social media, no 24-hour news cycles. Communication was different and lives were different. But rest assured, those affected by the tragedy — classmates as well as faculty, administrators and staff who were at Stetson in 1979 — had not forgotten. I was honored when Jill invited me to help her reconnect with classmates and begin the journey of remembrance, and memorializing Dennis, Katy, and Scotty.”

A Documentary Started and a Tower Reborn

One of the alumni contacted, Jep Barbour ’79 JD ’82, did not make the trip to Innsbruck in 1979, but Scotty Fenlon was his first cousin, a “very good friend,” a “tremendous athlete” and a Sigma Nu fraternity brother from Thomasville, Georgia.

“It was very devastating for me, and it’s still a tough thing to deal with,” says Barbour, now a Jacksonville attorney. “That was the first time I had ever lost a friend or even heard of someone my age losing someone their age.”

Barbour spoke at that memorial service in Lee Chapel of Elizabeth Hall all those years ago. The Sigma Nu house erected a flagpole and placed a marble stone in Fenlon’s memory; his football jersey still hangs in the fraternity’s trophy case.

Nonetheless, as Barbour describes, “Everybody moved on with their lives.”

As the Innsbruck ’79 alumni were reconnecting with Arroyo’s help, it was like a candle had been lit that quickly “turned into a fuse,” Jinks says.

It was Barbour’s idea to create a video documentary, and Karen Schmitt Roberts ’80, a North Palm Beach resident who sits on the advisory board for the College of Arts and Sciences, quickly and eagerly supported that idea.

“It’s something that has very profoundly impacted my life because I’ve never forgotten them,” Roberts says.

Especially during holidays or attending such life milestones as a wedding, she will think about her three classmates, “who were on a journey with you, and they’re not getting to do those things.”

Haunted by the tragic beauty of the bells that had rung out on that fateful day in 1979, and later that night as the local townsfolk lined the streets holding candles while the Stetson entourage proceeded to a local church, someone in those early discussions proposed incorporating Hulley Tower into any sort of memorial.

After sustaining damage during the 2004 hurricane season, Hulley Tower had been dismantled the following year, leaving intact only its mausoleum base where Stetson President Lincoln Hulley, PhD, and his wife, Eloise, remain interred today. The tower’s 11 bronze bells, named the Eloise Chimes, were salvaged and installed in various campus locations, and/or donated to community organizations.

A restoration of Hulley Tower was embraced by the alumni, and an official steering committee, with Barbour and Roberts serving as co-chairs, was formed in early 2023 to oversee both a documentary film and the tower rebuild.

The university has applied for a $500,000 historic preservation grant from the State of Florida, which entails a cash match. While that grant decision won’t be made until June 2024, the alumni have raised $500,000 in cash and irrevocable pledges for the rebuilding of Hulley Tower. A group of 12 alumni, trustees, neighbors, administrators and architects represented Stetson during the review process in Tallahassee, and the request ranked ninth out of 45 applications. The group is hopeful after that very positive outcome.

In addition to the grant process, the architects selected to oversee the historical reconstruction and surrounding courtyard design hosted a visioning session on campus with 70 stakeholders in attendance, including alumni, students, neighbors, city officials, faculty and staff. The “charrette” and subsequent focus groups will help to inform the design of the courtyard surrounding Hulley Tower. There is a strong desire for that space to be a place of remembrance, a place where various communities can come together and “feel” the soul of the campus.

Ongoing discussions with architects will determine the scope and final costs of the restoration.

Alumni also plan to purchase three bells crafted at the Grassmayr Bell Foundry in Innsbruck, and install them in the restored bell tower as a memorial to their departed friends. A fourth bell to honor the Innsbruck rescuers and a fifth bell in remembrance of survivors of the tragedy may be added.

The plans for the historically reconstructed tower include a full 52-bell carillon. Washington Garcia, DMA, dean of the School of Music, is leading that portion of the design process.

And You Films, a DeLand-based company headed by Will Phillips ’05 and Brendan Rogers ’07, producers and co-owners, is creating the video documentary. Alex Barratt, a New York-based digital video technician, also contributed stunning Innsbruck videography to the story. Barratt is the son of Tom (Toby) Barratt ’79, who was on the mountain that fateful day.

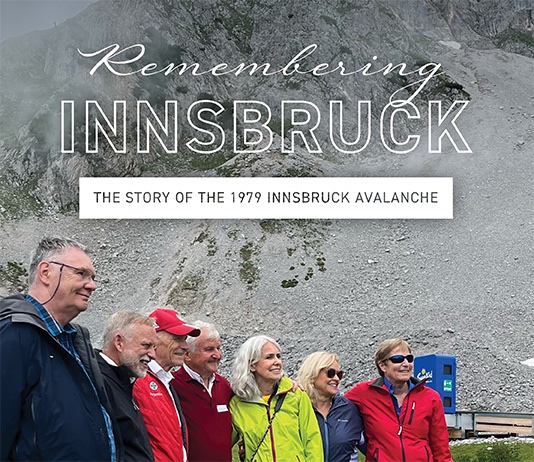

In July, Jinks, Brockway, Roberts, Spalding and Pavlik attended an alumni reunion in Innsbruck, along with university President Christopher F. Roellke, PhD; Steven Alexander, Board of Trustees chair; Dean Garcia; Arroyo; and other staff and faculty. The alumni experienced an emotional reunion with four members of the original rescue team. A number of attendees were interviewed on camera about their experiences those 44 years ago, with the footage contributing to the documentary. Stetson’s School of Music has created original music for the film.

In addition to a final version of the film, plans call for a shorter piece that can be shown to the Stetson community every year, perhaps during Homecoming, “in the vein of remembrance,” says Amy Gipson, associate vice president of Development and Communications, who also went to Austria and is Stetson’s lead person on the documentary. (A screening occurred during the 2023 Homecoming.)

Arroyo says she, Gipson and Krista Bofill, executive vice president and chief of Development, “are supporting this effort, but we are not leading it. It’s all been grassroots through this group of alumni. They are leading it, and it has been beautiful to experience.”

Scotty, Dennis, Katy and the ‘Soul of Stetson’

“Scotty was kind of a rock star on campus because he was such a great athlete, and he was just a great guy,” Jinks remembers. “I knew him to be really kind and, as we said then, a well-mannered Southern gentleman.”

“We were only a year apart in age and had similar interests in sports, especially golf, as we played in a number of junior tournaments together,” says Barbour. “He never told me, but I suspect he likely came to Stetson, at least in part, because I was there and it was a good fit for him. He joined my fraternity, Sigma Nu, and we had some great times together.

“Scotty was an easy-going, fun-loving, young man who had a great future ahead of him. I regret that we were not able to grow up, raise families and grow old together, sharing the joys and challenges of life.”

“Dennis and I were friends, and he was my roommate on the trip,” says Pavlik, who runs a marketing services company in Jupiter, Florida, that works with nonprofits as well as the outdoors/recreational fishing industry.

Dennis’ death “prompted me to make some life changes,” adds Pavlik, who had considered applying to law school but realized his heart wasn’t in it. “I changed my mind to the point where I thought, ’I’m going to do something that I’m interested in because I don’t know if I’m going to be here tomorrow.’ I didn’t make the most lucrative choices, but quite frankly I’ve never looked back and never been sorry for it,” he says.

Dennis’ mother mailed Pavlik an engraved graduation watch she had purchased for her son. “That was very moving to receive that from her,” Pavlik says.

Brockway and Katy were sorority sisters in Pi Beta Phi.

“Katy was from Massachusetts,” Brockway says. “She was quiet and a really deep-soul person. There were a number of Pi Phi’s on the trip, as well. She was a wonderful friend and thoughtful person.

“She came to Stetson a few years older than the typical freshman, having worked for a year or so out of high school. Her maturity added a wonderful dimension to our chapter, and her Massachusetts background was a welcome difference since most of our Pi Phi sisters were Floridians. It is wonderful to know that the Katharine Resnik award we established in her memory continues to be given to a Stetson Pi Phi to this day. I am humbled and honored to be a part of the project to rebuild Hulley Tower and in doing so remembering and honoring Katy, Scotty and Dennis.”

While the documentary will look back, the Innsbruck 1979 alumni are hopeful, even adamant, that their project will serve the present and point to the future.

“As this project evolved, we started calling it the ’Soul of Stetson’ because there’s something about this place that anchors people to it,” concludes Arroyo. “Jill talks about it as her ’why’ — it’s why she keeps coming back to this place and giving her time, her energy, her love, her resources, why she’s a Trustee. It’s this soul that anchors her here. She will oftentimes say, ’It’s in the dirt.’”

The alumni hope the restored Hulley Tower will be not just a memorial for their three friends, but that the monument, according to one steering committee document, “comes alive through programming, traditions, celebrations and remembrance.”

“I didn’t want to rebuild another vertical lighthouse that just sits there on campus,” Pavlik asserts. “President Roellke was very open to the idea that it would be a focus or gathering place for current students, even if it’s a bulletin board area where people get their news about what’s happening on campus. Or perhaps have yoga in the morning at dawn, and acoustic guitar in the evening.”

The tower, Pavlik and other alumni believe, will not only be a monument to yesterday, but also a testament to tomorrow.

That message, according to Pavlik: “Whatever knocks you down, there is going to be a tomorrow. Continue on. Keep moving forward. That’s what I’m hoping someone gets from this.”

“This desire has created an alumni-driven, and administration-supported, movement dubbed ’The Soul of Stetson,’ says Jinks. “It goes beyond what happened in 1979 to incorporate what is pure and true about our university — that its core values have stood the test of time, and, by standing tall, these values connect and sustain the Then, the Now and the Next. It is about creating spaces and rituals that are founded on our shared values. And that is good … .”

Editor’s note: If you would like to know more about these events, or want to watch the documentary or contribute to the Hulley Tower reconstruction, visit Stetson.edu/remembering-innsbruck. Or, contact Amy Gipson at agip[email protected].

-Rick de Yampert

Atlanta Premiere of the “Remembering Innsbruck”

Sunday, Jan. 21, 2024, noon-2 p.m.

Piedmont Driving Club

1215 Piedmont Ave. NE

Atlanta, GA 30309

More information and to RSVP (by Jan. 10).

Questions? Call 404-803-3988.