Nobody Ever Listens to Teenagers

“When you empower people they can organize and do incredible things.” –Florida Rep. Kathleen Peters

Adolescents are often told two conflicting messages: speak and be silent.

We are told we can do anything—that we can “be the change we’d like to see in the world” —yet in that same breath, our initiatives are patronized, and we are told to sit back down at the kids’ table where we belong.

Together we mumble the words, “Nobody ever listens to teenagers.”

However, State Rep. Kathleen M. Peters, R-District 69, who spoke at Stetson about ‘Community Organizing and Policy Approaches to Solving Complex Problems,’ spent the crux of her political career doing just that: encouraging young people to make a change.

When we think of community leaders, most of us think of people with titles—elected officials or CEOs—but Peters found that to be largely untrue.

“There was a 16-year-old girl from Seminole High School,” said Peters. “She and two other members from that same high school, were probably some of the strongest leaders in Pinellas County, (Fla.) advocating for youth and creating a teen center at a time when the city wanted to put in curfews at 9:00 p.m.”

That 16-year-old girl was no other than Stetson’s own Tara (Calderbank) Batista, Ph.D., visiting assistant professor of management in the School of Business Administration, ENACTUS faculty sponsor, and Stetson alumna, class of 2005.

Now with 15 years of experience in non-profit management and social enterprise, Batista currently advocates for social responsibility within the corporate sector and strongly believes in youth empowerment.

And it all began in June 1999 with a vaguely written letter.

While touring universities during Batista’s college admission process, admission officers told their prospective students one thing: “There’s thousands of people who apply with a 4.0 G.P.A. How are you going to stand out from that crowd?”

It was then that Batista decided that if an opportunity ever landed on her desk, she would take advantage of it.

And then it did.

“I’d just gotten home and opened the letter up on my kitchen counter,” said Batista. “It had the America’s Promise letterhead on it and said this was a ‘challenge for teenagers to leave a legacy for the year 2000’ by doing a community project.” Despite the ambiguity, it drew Batista in. “It was the first time I heard the term ‘youth empowerment,’ and I liked the sound of that.”

In 1999, while working for the Juvenile Welfare Board, an agency funding youth initiatives, Peters was tasked with executing The Millennium Celebration Legacy Project, aided by America’s Promise, a program that challenged minors to leave a lasting legacy in their communities before the new year.

Peters answered the challenge by seeking out talented students recommended by local teachers.

Lynda Lippman-Lockhart, Batista’s influential high school English teacher, recognized her student’s ambition and sent out her nomination. Out of the 60 letters sent out, Batista was the only student to respond back and commit, recruiting friends and peers until 120 Pinellas County high school students eventually were a part of the project.

“I got my best friend to feel sorry for me,” said Batista. Attending meetings, Batista—besides two girls who soon dropped out—was the only active participant. “I’d been complaining and, just to get me to shut up, she said ‘Okay, I’ll come with you.’ Which was great because Kelly was a lot cooler than I was.”

Within two weeks of their collective networking, “Kelli tapped into the cool kids and I tapped into the geeks,” said Batista. “Sixty high school students and one middle-schooler joined the team.

“My pitch was always the same,” said Batista. “I said, ‘You have to do 75 hours of community service to get the Florida Bright Futures Scholarship anyway. Would you rather spend that picking trash off the side of the road or spend it creating something that’s your own, making yourselves stand out to colleges—and eat pizza and drink Coke while you’re doing it.’”

Even Peters was surprised by the growing fervor.

“We had seven months to do this, and I thought, ‘no problem, we’ll do a peace garden or a park,’” said Peters. But it soon became evident that these teenagers were thinking of something a bit more grand scale. “They wanted to build a teen center,” said Peters. “And do you know how much money I had? Nothing.”

Despite the daunting difficulty of funding, Peters did not dissuade these teenagers from their vision. Instead, she guided them to reach out to local-non-profits and get local media attention. In order to receive the initial grant of $195,000 from the Juvenile Welfare Board, Batista had to persuade the president of St. Petersburg Junior College (SPJC) to donate its grant writing services as well as do independent research in order to draft the grant with the other teens on the board.

“We’d be given official letterhead and envelopes with the logos, and we would type up letters to companies requesting in-kind donations,” said Batista. “It worked out well, but sometimes I did things like write a press release with grammatical and spelling errors and send it to the newspaper. “They had so much trouble reining us in.”

The assigned SPJC grant writer was initially wary of working with teens, thinking they would compromise her hit ratio. However, she found that they were more than willing to effectively do their part. The autonomy the teens had—over the research, the execution and the upkeep of the center—furthered the project instead of hindering it.

“Young people are going to make mistakes,” said Batista. “But you have to let them.”

Not only did they receive the funds needed to create the 61st Central Teen Center (61C) in Pinellas County, they later received a $660,000 grant from the Eckerd Family Foundation to expand the project to five other local communities.

Serving more than 350 teenagers from across the county with workshops, activities and programs, 61C had one simple motto: “created for teens, by teens.”

The center created a council, made up of 40 teenagers and an adult sponsor, who independently designed, interviewed and hired a salaried project director and a program coordinator to complete the executive board.

Serving as chair of Programming on the executive board, Batista made sure to take full advantage of the autonomy given to them. “We were encouraged to think big,” said Batista.

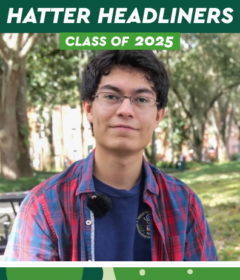

Matthew Morton ‘06, the center’s public relations chairman and future chair of Programming, also later attended Stetson University. He shared what 61C did for the community at the time. “It offered us what we never had before, and that’s a place to go.” (In the photo on the front page of Stetson Today, Matt Morton honors Tara Batista in an appreciation ceremony.)

Looking back, Batista admits that her reason for following up on the America’s Promise letter was not exactly a selfless one.

“I wish I could say that my motivation was because I saw all these social problems and wanted to make an impact,” said Batista. “But I was 16 and wanted to get into a good school.”

Needless to say she did get into a good school, and Stetson is lucky to have her.

Simply put, Batista “dared to be significant” before she knew who John B. Stetson was.

Under Peters’ facilitation and guidance, Batista, Morton and all the local teenagers involved created a safe space for all the teens in their community—their legacy—by refusing to be ignored; by demanding to be heard.

“When you empower people they can organize and do incredible things,” said Peters.

Peters said she began her career as a girl who hated politics, but always wanted to make a difference—especially in the lives of adolescents living in communities that were written off.

“She really is responsible for making this happen,” said Batista, but Peters disagreed.

“Tara always says that I was her mentor,” said Peters. “But I always thought she and her friends were incredible mentors to me.”

By Veronica Faison