Saving Florida’s Aquatic Gems

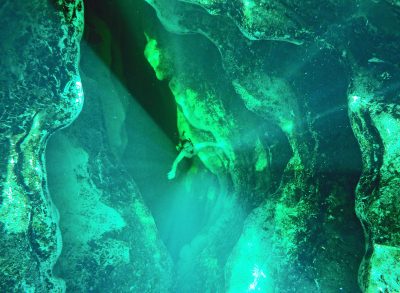

Stetson University Professor Robert Sitler started freediving in local springs when he moved here 23 years ago.

Since then, he has seen alarming changes beneath the surface.

“The degradation has been very notable just in two decades of swimming there — in all of them,” said Sitler, Ph.D., professor of World Languages and Cultures at Stetson. “To the untrained eye, it’s like, why is there algae growing everywhere? Why is the water getting greener? Why am I not seeing certain kinds of fish? Why am I seeing all these invasive fish?

“It’s an unfortunate litany. … The loss that I was seeing right in front of my eyes was a motivator, for sure, for trying to do something about it,” he said.

This month, Sitler unveiled a project that’s been in the works for two years, ever since he bought a GoPro waterproof video camera in the summer of 2015. With that and an inexpensive camera in his pocket, he and his wife June set out to highlight “Florida Aquatic Gems” within 30 miles of Stetson’s DeLand campus, documenting the beauty above and below the water’s surface.

Sitler hopes the photos and videos on his Florida Aquatic Gems website will encourage others to preserve the area’s imperiled water resources. His website provides links to learn more about the threats, including pollution and over-pumping, and includes maps for people to visit the sites located on public lands.

“I’ve been fortunate in my travels and I don’t think there’s anything else – any comparable size area in our continent that has the diversity of aquatic resources that are around us,” said Sitler, who has traveled extensively in Mexico, Central America and South America.

“If you look at a map of the entire Eastern Seaboard, Volusia County is the only interface where you have the seaboard and massive springs. That alone is unique, but you add to that the St. Johns River basin, saltwater and freshwater marshes, the second largest lake in the state and the whole thing sits on top of the aquifer. We’re really in an unusual and privileged place here,” he said.

The Florida Aquatic Gems project “functions in support” of Stetson’s Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience, an initiative that demonstrates the university’s “commitment to healthy waters and a ‘greener’ future,” according to his website. The website provides links to Stetson’s Water Institute and other Stetson programs, including Environmental Science and Studies, and Aquatic and Marine Biology.

Clay Henderson, executive director of the Institute and a noted environmental attorney, said he has talked with Sitler about the project from the beginning and believes it will help the Institute advocate for more protections for the springs and other natural resources.

“He has a strong interest in springs and his photography is remarkable,” Henderson said. “It’s telling the story. I’ve said it so many times. We under-appreciate our springs. There are more first magnitude springs in Central Florida than anywhere else in the world. Anything that brings awareness to our springs and shows their intrinsic beauty helps our overall advocacy.”

Henderson agreed that the area’s aquatic diversity is unrivaled.

“Florida is a state defined by water, but it’s even more true for Volusia County,” he added.

A Deeper Connection to Water

Sitler describes himself as a lifelong environmentalist who has always enjoyed the outdoors. While pursuing a doctorate at the University of Texas – Austin, he learned how to free dive in Barton Springs, a place inhabited by people for 10,000 years. The experience began his love of free diving in springs, unburdened by bulky scuba equipment.

At the University of Texas, he studied Hispanic literature and was drawn to “all things Maya,” eventually becoming an expert on Mayan culture and traveling extensively to Mayan communities. His relationships with the indigenous peoples of Central and South America gave him a heightened appreciation of water conservation.

“Within those communities, which are closer to the ground, if you will, and closer to the edge of survival, the appreciation for water is heartfelt because they need it to survive. There is a deeper connection,” he said.

Mayan history also tells a story about the vital need to protect water supplies.

“The significance of water in Maya culture has been reinforced by a tragic history that goes back thousands of years, where inattention to water protection has led to – I won’t use the word, collapse – but a rapid degeneration of society and eventually abandonment of urban centers,” he said. “Something that complex has numerous reasons behind it. In my own mind, the environmental issue was probably the principle reason that people ended up abandoning these cities and that environmental issue was water.”

This Mayan connection to water “naturally” led Sitler to focus on environmental issues closer to his DeLand home, especially ones involving water conservation.

Changing Behaviors

Then, a few years ago, he saw a project by the Gainesville Sun and Ocala Star-Banner, called “Fragile Springs,” that explored North Central Florida’s imperiled springs system and featured a multimedia website with “incredible” photography and video.

“The first image on the website was incredible,” he recalled, adding that it inspired him to highlight local springs and waterways. “I imagined a website that would feel like you were immersed in water, that you would shift from one aquatic realm to another.”

For two years, the self-taught photographer visited nearby aquatic sites, including during a sabbatical in the spring of 2016. Today, his website features 20 aquatic sites, including Holler Fountain in Palm Court on Stetson’s campus. It shows a beautiful aerial shot of Palm Court, taken with a drone that his children gave him on his 60th birthday. He has a license from the FAA to fly drones and has included aerial photography from many of the aquatic sites. (All of his photos are available for sale on the website.)

Sitler plans to add more aquatic gems to the website over time. By showing their beauty, he hopes to educate people about the environmental damage that is occurring, and motivate them to take action to protect and restore these treasures.

“There are practical things that people can do to break normalized behaviors that, unfortunately, are the cause of all this,” he said.

Adding fertilizer and irrigating lawns wreak havoc on the environment. Fertilizer washes into waterways, feeding algae growth and depleting oxygen for fish. Irrigating with freshwater requires more and more pumping from the Floridan aquifer, one of the most productive in the world, and depletes the flow from the natural springs. Add to that 100,000 septic tanks in Volusia County, contributing more nutrients and pollutants in their runoff, and the end result is a looming environmental crisis.

“We know why all this degradation is happening,” said Sitler, who plants only environmentally friendly native species in his yard. “There are no mysteries. This isn’t some secret thing. We know exactly what we have to do, but we aren’t doing it.”

-Cory Lancaster