Freedom Riders

This article appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of Stetson University Magazine, available online.

Since 2006, more than 300 Stetson students have participated in a life-changing historical exploration, retracing the steps of the Freedom Riders and meeting many of those courageous individuals in person.

The six-city travel experience, part of the curriculum for courses at both Stetson Law in Gulfport, where it was established, and the undergraduate program in DeLand, exemplifies what a Stetson education is all about: providing students with the opportunity to engage in experience-based, transformative learning.

Not only for educational purposes, but for life. So, in a sense, the students, too, are freedom riders.

Freedom Riders — civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the southern United States in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals — played a significant role in the civil rights movement by placing a great deal of pressure on the federal government to safeguard civil rights. In turn, they inspired African Americans in the South to act against their infringements and provided a real-life example of what we’re now seeing again nearly 60 years later — blacks as well as whites taking immediate action for more civil rights.

Robert “Bob” Bickel, former Stetson professor of law, created the tour as part of his Constitutional Law and the Civil Rights Movement class, and partnered with Tammy Briant, JD ‘06, to grow the experience. He has since retired, and Briant is no longer teaching, but the program continues to grow and now includes undergraduates who take a Religion and the Civil Rights Movement class taught by Greg Sapp, PhD, professor of religious studies and the Hal S. Marchman Chair of Civic and Social Responsibility. (Briant is now executive director of Community Tampa Bay, whose mission is to cultivate inclusive leaders to change communities through dialogue and cross-cultural interaction.)

The travel experience, of course, was canceled this summer due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, history is repeating itself. And the lessons still resonate.

“I think the description students use year after year is ‘life-changing,’” said Sapp, a graduate of Stetson, Class of 1988. “The impact isn’t only historical; there’s a strong contemporary component to it, as well. Students learn that the motivations that fueled the segregationist practices through the 1960s remain and must be fought continually.”

During previous trips, students and faculty visited the Nashville Public Library Civil Rights Collection, the National Civil Rights Museum, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, the Southern Poverty Law Center and National Civil Rights Memorial, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, the Rosa Parks Museum, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Change. They also visited sites of the major events in the civil rights struggle in Memphis, Nashville, Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma and Atlanta.

“The most meaningful component of the experience is getting to meet the people who were there, who marched with Dr. King, participated in the Montgomery bus boycott, and were beaten and imprisoned for participating in the Freedom Rides,” asserted Sapp. “You can read about it in textbooks all you want, but when you’re sitting in a room with someone who lived it, you can’t replace that kind of experience.”

Rip Patton was one such Freedom Rider. Since 2007, he’s been a major part of the experience, each year traveling on the bus with the students and introducing them to other Freedom Riders who meet with them.

Patton was involved in the Jim Lawson workshops in late 1959 and early 1960, preparing for the Nashville sit-in movement, before he became one of the original Freedom Riders. Also, he was one of the original members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and was part of a group of about 10 of those committee members who in 1961 met with Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade King to join them on the Freedom Rides. Patton worked closely with other Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leaders, such as John Lewis, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette and Julian Bond. (See sidebar below.)

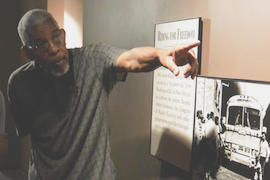

“I have photographs of Rip walking through museums, and our students are crowded around him as he points at pictures on the wall, recalling who these people were and what they did,” Sapp said.

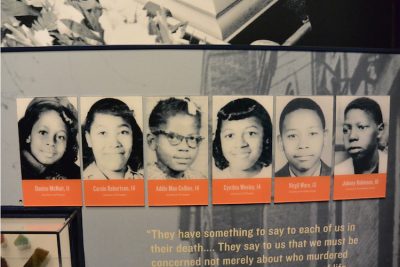

Stetson students stood in Kelly Ingram Park, where schoolchildren were attacked by dogs, knocked down by water cannons and arrested (and jailed) for marching for equal treatment. Students shed tears standing beside the 16th Street Baptist Church at the spot where a bomb was placed by Ku Klux Klan members that killed four young girls who were preparing to participate in Youth Sunday.

“We got to visit with Denise McNair’s father,” said Sapp. “Denise was one of the four little girls who was killed in the church bombing. He passed away recently, but for the students who met him, it was an experience they will never forget.”

Whether standing beneath the balcony where Dr. King was assassinated, or marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where voting rights marchers saw police officers lined up at the base of the bridge with clubs and gas masks, being in such places leaves indelible impressions.

“I tell my students that these marchers were undergraduate students just like them,” Sapp noted. “They were standing up to white supremacy and white control, and they were demanding equal treatment.”

For Micheal Jenkins, who was born in Mississippi and grew up in south Georgia, the experience truly was compelling and captivating — a chance for him to see up-close and personally while some of the participants are still alive to share stories. Jenkins took the course trip in summer 2018 following his first year at Stetson Law.

“It’s something that, one, I never can forget. And, two, it just opened my eyes up to so much more than I think just the normal population has,” said Jenkins, who graduated from Stetson Law in May.

“I understood how important the movement was going into [the course]. But what I didn’t fully understand was how many everyday people played a role in this movement, how important they were. … There was so much more to this movement.”

The lessons reached Stetson students and staffers alike.

“You get to the point where you feel it’s safe to cry, because you do cry,” commented Rina Tovar Arroyo, assistant vice president for Development, Parent and Alumni Engagement. “When we walked up to the very spot where Martin Luther King was killed, an audible sob came out of me. I mean, it was so powerful. We just stood there together in silence.”

Arroyo watched, listened and learned. During that experience, she was a student, too.

Arroyo remembers one particular moment in Montgomery at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration.

“This was such an eye-opening experience in which I was filled with rage, shame and pure horror at the brutal history I was not taught in school,” she recalled. “There were many moments that I broke down and was feeling ashamed on so many levels as a white American woman. That was when I walked around the corner, and there was Rip Patton, sitting down with a white family — a mom, dad and two little children. They were looking at him with admiration and amazement in their eyes! They had just seen his photo on one of the walls, honoring the Freedom Riders, and then they realized this real-life hero was standing in front of them.

“He sat down and told them stories of the Freedom Rides, and he made sure to tell them that they could not have done what they did without their white brothers and sisters. He thanked their parents for bringing them to the museum and gave them hugs.”

GENEROUS BENEFACTORS

As a member of the Bonner Program during her first year on campus in 2016, Ali Van Gundy ’19 was already interested in community transformation and social justice. Van Gundy took Sapp’s Religion and the Civil Rights Movement class in the spring and participated in the travel experience that summer.

“Each person has a different experience based on his or her background, but it’s extremely meaningful for everyone,” she noted. “I never had coursework that was as deeply emotional and felt so personal. The trip connects you to history in a unique way.”

The travel experience was so amazing, Van Gundy went a second time two years later. Not coincidentally, her parents gave a major gift to endow the program.

Courtesy of Kim and Stan Van Gundy, the gift covers scholarships for each of the undergraduate students who take the summer class and their trip expenses. In addition, the gift subsidizes some of the law students’ expenses. At the time, Kim was a member of the Stetson University Board of Trustees. Stan is a former head coach in the National Basketball Association.

“As a trustee, I knew it was important to support the mission of the university in every way possible,” said Kim. “Knowing our passion for social justice, when Dr. Libby [Wendy B. Libby, PhD, past-president] and Rina Arroyo offered us the opportunity to endow this program, we immediately knew it was something we wanted to do. We saw the significance and importance of the trip through Ali and knew it was something every student should have the opportunity to experience.”

Stan confirmed that in terms of any kind of academic experience, it was the most impactful thing Ali did during her time at Stetson.

“You’d hate to see an experience like that only be possible to students who had the money to do it,” he said. “It should be open to anyone, and that was our motivation for getting involved.”

Ali specifically remembers going back to the hotels at night, where the students would stay up and continue the conversations they were having on the bus. The time spent talking and reflecting about the things they experienced earlier in the day allowed them to process all of it.

“It’s the kind of thing that motivates you,” she explained. “It’s one thing to read about history, but it’s another thing to experience it like that. From a historical perspective, it adds so much to your understanding when you hear it from the people who actually lived it. That’s invaluable.”

The Van Gundys also are involved in Stetson’s Community Education Project at the Tomoka Correctional Institution, as well as a community coalition led by Stetson Professor Emeritus Grady Ballenger, PhD, and community leader Sharon Stafford, to claim Volusia County’s monument from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The Van Gundys recalled a recent conversation with Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative.

“[Stevenson] talked about the importance of education and confronting our true history,” Kim said. “This course provides an opportunity for students to do that. It’s important all schools revisit our history and confront it in a way we haven’t yet. There’s a lot of unlearning and relearning to be done.”

Stan found it interesting how Stevenson contrasted the way in which the issue of race has never truly been confronted in the United States; meanwhile, Germany has dealt with its history, coming to grips with the past and dealing with it as a society. Stevenson noted that, as a result, the entire country of Germany has been committed to wiping racism out, according to Stan.

“If you don’t understand the history of slavery, then you don’t understand Jim Crow [racial segregation], what the people in the civil rights movement were fighting for and what they had to sacrifice just to get the right to vote,” Stan commented. “We have to understand the history of this, and when these students get a chance to have a personal connection with people like Rip Patton and understand what really went into this and what this struggle has been like, it’s transformative.”

“Maybe the biggest thing I learned, when I went on the trip, is that we’ve overcome so much; we’ve come so far. But we still have so far to go,” said Jenkins.

“There are just so many similarities to what happened in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s to what’s happening today. … The parallels are just so astounding.”

Sapp stressed the importance of learning experiences that compel students to use critical thinking skills in order to try and better understand the world around them. He encourages students who want to enhance their Stetson education to get involved and take advantage of whatever opportunities may interest them.

“When you get students out into the community, they realize how messy life can be, and that’s the great thing about experiential learning,” Sapp said. “This particular travel experience represents an outstanding opportunity for our students. When you see how their lives are transformed as a result, it makes you feel good as an educator.”

From the perspective of starting out in his legal career, learning about the Freedom Riders and their civil rights movement certainly will help, said Jenkins. Yet, even more, the lessons will last a lifetime.

“You can’t take this course without becoming a better citizen,” he concluded. “But this was a life lesson, in general.”

-Jack Roth

Freedom Leaders

In the days before the Summer 2020 issue of Stetson University Magazine was published, two leaders of the civil rights movement from decades ago passed away. Both of them, Georgia Congressman John Lewis, and Rev. C.T. (Cordy Tindell) Vivian, once lectured at Stetson.

Lewis, often described as “one of the most courageous persons the civil rights movement ever produced,” was a speaker at Stetson on Jan. 25, 1999, as part of the university’s Howard Thurman Lecture Series. Lewis spoke about his book “Walking with the Wind.”

Similarly, C.T. Vivian, a friend and close adviser to Martin Luther King Jr., visited Stetson on Jan. 12, 2000, presenting the lecture “Martin Luther King: 21st Century Man.”

From 1963 to 1966, during the height of the civil rights movement, Lewis was chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which largely was responsible for organizing student activism in the movement. While still a young man, Lewis became a nationally recognized leader. By 1963, he was dubbed one of the Big Six leaders of the movement, and at age 23 he was an architect of the historic March on Washington in August of that year.

Vivian was active in sit-in protests in the 1940s and met King during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott — a demonstration spurred by Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat to a white rider.