A Connection to the Smithsonian Institution

Usually at this time of year, the Gillespie has joined museums across the nation in a fall ritual, Smithsonian Museum Day. This year’s celebration has been rescheduled, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To us, though, the event has always marked a passage, like the equinox, to a new academic and exhibit calendar.

We’ve especially delighted in using the day to point out that it was a mineralogist, James Smithson (c. 1765-1829), who founded our national museum system. Smithson conducted research in mineralogy and geology throughout western Europe, and was recognized for his accomplishments by the Royal Society of London in 1787.

Scholars are still a bit puzzled why an English gentleman and natural scientist would bequeath $508,218 to the people of the United States to found “an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” (It took Congress another eight years to agree that the U.S. should have a centralized museum system.) His founding gift established the Smithsonian Institution, currently the world’s largest museum complex, and its original mission aligns with our own “to promote the study, appreciation, and understanding of the natural sciences in Central Florida.”

But there are other connections. One of the museum’s most extensive mineral suites is of a zinc carbonate (ZnC03), now known as Smithsonite. James Smithson conducted experiments on zinc ores, which were at the time known as a single class, calamine. His research, published in 1809, demonstrated that there were in fact two minerals, zinc carbonate (a good ore for zinc) and a zinc silicate (now generally known as hemimorphite, not a good source of that element). For this discovery, and for the simple chemical test he developed so that miners could identify it in the field, Smithsonite was named in his honor.

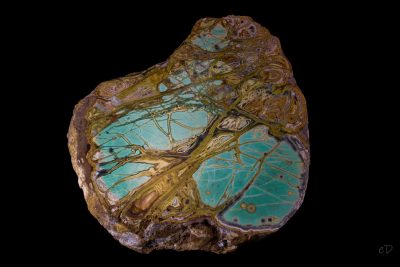

Beyond its usefulness, Smithsonite is a beautiful mineral, prized by collectors for its range of crystal structures and colors. The Historic Gillespie Collection includes 42 Smithsonite specimens, from Arkansas and Arizona to Namibia and Greece.

The Gillespie Museum has another link to the Smithsonian, through storied specimens collected by our own founders, T.B. and Nellie Gillespie. In the 1950s they traveled to the Little Green Monster Mine near Fairfield, Utah—the claim of well-known mineralogists Arthur Montgomery and Edwin Over, both of whom advised the Gillespies on where and how to collect fine minerals. On that trip the couple found large specimens of Variscite (AlPO42HxO), which were “sawed and polished” by the Mineral Department of the Smithsonian. As was the custom, the fee for service was the other half of the nodules, so many of the variscite specimens in the museum, along with others (including Montgomeryite and Overite) have twins in Washington.

We look forward to opening the museum’s exhibits to visitors when it is safe. But if you’d like to learn more about what’s on our shelves, follow our Mineral Monday, A-Z, posts on Facebook and Instagram, curated by Gillespie Museum Guides Yasmin Nagah Abdou and Caitlin Bhagwandeen. And sign up for our newsletter.

-Karen Cole, PhD

Director, Gillespie Museum