Foreman Biodiversity Lecture addresses potential red tide causes, solutions

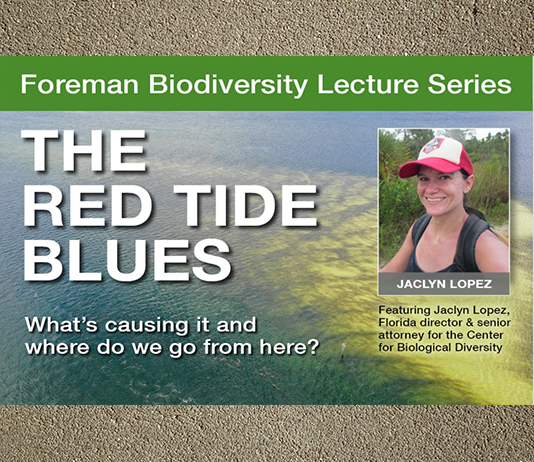

The first Edward and Bonnie Foreman Biodiversity Lecture Series event of the 2021-2022 academic year featured Jaclyn Lopez, Florida director and senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity in St. Petersburg. Her presentation, “The Red Tide Blues: What’s Causing It and Where Do We Go From Here?” covered red tide (a/k/a Karenia brevis) and some of its causes.

Karenia brevis is a type of algae that occurs in marine waters. It normally lives 40 miles off the coast of Florida and prefers a salty environment, but winds and other elements can push it to shore, where it can move into brackish and estuary waters. It occurs naturally in small amounts but can become concentrated – or a bloom known as red tide – when fed a diet of phosphorus and nitrogen.

Concentrated levels of red tide produce neurotoxins that can kill marine wildlife and make humans sick. Humans can experience respiratory issues leading to hospitalization or get sick from eating contaminated seafood. It can even kill people, though that is rare, Lopez said.

For marine wildlife, the effects of red tide are more serious. Manatees are especially vulnerable because they inhale aerosolized red tide particles when they emerge for air, as well as consume the toxic algae when they eat sea grasses. The Tampa Bay area alone logged about two dozen manatee deaths since June that were likely attributable to red tide, Lopez said.

Where does red tide come from?

Predominantly from human activity, Lopez said. Pollutants reach the ocean though both “point sources” and “non-point sources” (as defined by the Clean Water Act). Fertilizers and other pollutants, including lawn clippings and animal droppings, create toxic runoff from cities and residential neighborhoods that end up in the water systems. Corporations discharge pollutants directly into streams and rivers. Farms generate fertilizer and animal waste that can run off or seep into groundwater. Wind erosion and spray drift pull pollutants into the atmosphere, which end up in the ocean when it rains. The phosphorus and nitrogen from these various sources fuel harmful algal blooms.

Lake Okeechobee

A 2020 lawsuit, Center for Biological Diversity, Calusa Waterkeeper, Waterkeeper Alliance v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, focused on the management of Lake Okeechobee. In 2018, Florida saw sustained red tide on the west coast for about a year, as well as blue green algae (a cyanotoxin with similar effects to red tide) on both coasts. Marine wildlife and residents had nowhere to go to escape the blooms, Lopez said.

Lake Okeechobee is hydrologically connected to both coasts, and the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers is the federal agency responsible for pushing the lake levels out to the estuaries when water gets too high. Center for Biological Diversity attorneys argued in their lawsuit that the Army Corps’ management of the lake was contributing to harmful algae blooms. The Army Corps, in its defense, acknowledged that red tide is harmful to marine wildlife but claimed that discharge and nutrients from Lake Okeechobee do not fuel red tide. They agreed the discharges could contribute to blue green algae, but claimed the blue green algae posed no threat to marine wildlife.

A 2020 research paper by Miles Medina, who was working on his Ph.D. at the University of Florida, showed how the discharge of nutrients contributed to the persistence of red tide, demonstrating the phenomenon is driven by humans, Lopez said. She added that the common argument that red tide is “naturally occurring” is a “throw away, fluff adjective” meant to distract from the key point: Yes, Karenia brevis is a natural occurrence, but concentrated blooms of it are not.

The nonprofit agencies were successful in their lawsuit in compelling the Army Corps to reinitiate consultation, under the Endangered Species Act, with the Fish and Wildlife Service to figure out how the discharges are impacting manatees and other marine wildlife. The Corps also is in the process of reviewing how they handle discharges from Lake Okeechobee.

Piney Point

Phosphogypsum is the waste leftover from producing phosphoric acid, which is used in fertilizer. Florida is the largest producer of phosphoric acid in the United States. For every one ton of phosphoric acid produced, five tons of phosphogypsum are created. This byproduct, which contains concentrated levels of lead, cadmium, chromium and other radioactive carcinogens, is dumped into large ponds called phosphogypsum stacks or “gyp stacks” designed to hold the waste indefinitely.

It was well known among industry and government leaders that the Piney Point gyp stack near Bradenton was in a state of severe disrepair and at risk of failure, Lopez said. Over Easter weekend of 2021, a series of catastrophic issues led the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to authorize the discharge of up to 480 million gallons of water from the top of the gyp stack to try to prevent it from collapsing completely and flooding area homes.

From April 30-May 9, 2021, about 215 million gallons of waste, including 200 tons of concentrated nitrogen, was discharged from Piney Point into Tampa Bay. Essentially, Lower Tampa Bay got as much nitrogen in under two weeks as it usually sees in an entire year because of the dump. Localized algae blooms were observed shortly thereafter, with significant red tide blooms by mid-May. It continued through mid-July, along with concentrated fish kills along Pinellas County coasts.

Center for Biological Diversity is now suing the DEP, arguing state officials were aware of the potential failures of Piney Point and yet pushed the gyp stack beyond its limits. About 10 years ago, DEP authorized Piney Point to receive dredge material from the Bishop Harbor dredge. The Army Corps, which was part of that permitting process, objected, citing in its report that not only are gyp stacks not engineered to hold dredge material, but Piney Point, with its history of failures, would almost certainly collapse under the added material. Despite the warning, the DEP and Piney Point owners moved forward with the plan.

What’s next?

Piney Point is only one of 24 other phosphogypsum stacks covering 11.1 square miles of Florida. Another 837.9 square miles of the state are either current phosphate mines, planned mines, closed mines built before 1974 and therefore have no plans to restore or reclaim them, or land owned by mining companies. There are 50,000-100,00 acres of phosphate mining left in Florida – not being dug yet, but that will be dug in the next 20-30 years, Lopez said. That will likely result in the addition of another half billion tons of phosphogypsum over time, all of which will remain in Florida. Meanwhile, more than 50 percent of the phosphoric acid produced is exported. The rest goes to produce food crops, primarily corn and soy, for cows and chickens, which are either eaten or exported.

“But we keep all of the waste,” she said.

How can you help?

Lopez says the “simplest” answer is to vote – and not only for the people who make the laws, but for those who implement and enforce them. Executive agencies such as the DEP fall under the office of the governor, so “it’s really important that we’re electing a governor that prioritizes environmental protection – or whatever your issue is. And not just on paper, not just to get the photo op, not just for running for reelection, but for tangible results.”

Stetson Law students should also consider joining the Environmental Law Program, as well as explore internship or externship opportunities with agencies such as National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and the Summer Honors Program for Law Clerks in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of General Counsel. Placements in private law firms with strong mentorship programs that will help them learn critical advocacy skills and gain real life experience can also be useful, Lopez said.

Becoming members of nonprofits, such as Tampa Bay Waterkeeper, Tampa Bay Estuary Program and others, is another good action step. Stetson Law students can apply for financial support from the Dick and Joan Jacobs Externship Fund to help support their nonprofit environmental work.

Lopez, a Florida native, insists the story is not all doom and gloom. The state has a resilient ecosystem, and the time and money put into Tampa Bay so far have helped its recovery over the last 20 years, but the effort is ongoing.

“We have a lot of work to do in our region to take care of our water bodies,” Lopez said.

About the speaker

– Ashley McKnight-Taylor

[email protected] | 727-430-1580