Personifying First Gen

First Gen — as in the first generation in their family to attend college.

Even that moniker carries a measure of misunderstanding or at least the need for clarification. The definition can be complicated.

According to both the Center for First-Generation Student Success and the U.S. Department of Education, being a first-generation student means your parents (or legal guardian) did not complete a four-year college or university degree, even if other members of the family have.

Further, many colleges and universities consider students with parents who attended international universities as First Gen. That includes Stetson.

At the same time, some colleges view those same students as continuing-generation — not First Gen — if either of their parents attended a postsecondary institution, regardless of whether they actually obtained their degrees. Those parents might have earned an associate degree, received postsecondary vocational training or earned certifications to prompt the Continuing Gen designation for their children.

As a result, for starters, the national landscape is uneven.

In addition, student resources on campuses are often tied to those designations, magnifying their importance, with accessibility of support and aid at issue. Statistically, the First Gen population has fewer financial resources than other students. Also, they pursue college-level education at lower rates and are less likely to attain four-year degrees.

Then there are the inherent challenges of simply being first, regardless of definition. As examples, consider the expectations and family-driven pressures to succeed academically, the adaptation to campus life, finances, social anxiety and perhaps stigma. Often, First Gen students feel alone in their experiences, with family members being unable to relate to college. And some students feel a sense of shame because they have taken on a First Gen identity.

More than with many other students, questions are apt to abound — generally, what to do and how to do it without any substantial insight from home.

As a First Gen student, maybe you remember your earliest days on a college campus.

Nationally, one in three undergraduates identify as first-generation, and those numbers are expected to increase in the near future, with the pipeline of first-time undergraduates heavily weighted with First Gen students, as revealed through data from the Center for First-Generation Student Success. The center is a partnership between the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators in Washington, D.C., and The Suder Foundation, which has the stated mission of advancing societal transformation through higher education.

At the same time, First Gen success typically carries intergenerational impact, with successful college completion being a significant predictor of educational, job and life achievement for the families of graduates.

Not coincidentally, the prevailing belief is that institutions of higher education must shift their mindsets and priorities to better serve First Gen students in order to survive, thrive and meet their missions.

Is that happening at Stetson?

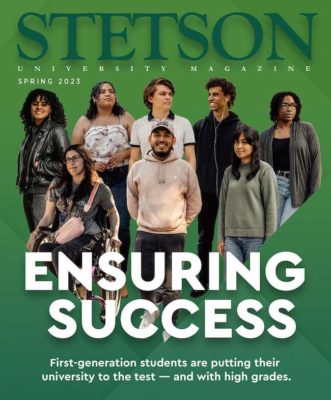

During this spring’s semester, there are 700 first-generation students on the DeLand campus, representing more than 25% of the student body, as counted by Stetson’s Office of Institutional Research & Effectiveness.

Six of those students share their personal stories, as well as perceptions about their university.

For the complete story, read the printed version of Stetson University Magazine in mailboxes soon or the digital version here.

-Michael Candelaria

Editor’s note: With the Fall 2023 issue, we will be introducing a more robust digital version of the magazine. To opt out of the print version in the future, please email that preference to [email protected].