Coming Back to Campus

Editor’s note: This is the final part of a three-part series, Sharing Their Stories.

In the fall of 1964, six African American freshmen enrolled in Stetson and, four years later, three would graduate from the university.

The Stetson class of ’68 included Jim Johnson, Maurice Woodard and William Strawter, a retired vascular surgeon who now lives in California. Two of the six students didn’t return after their freshman year, and Franklin Biggins, the retired judge, left after his sophomore year, saying the environment in DeLand was too challenging for a student of color.

Biggins had attended an integrated high school in Pennsylvania and hadn’t been a victim of segregation. He found it difficult to live in the small, segregated southern town of DeLand. He withdrew from Stetson and earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of South Florida and a law degree from the Catholic University in Washington, D.C.

“You have to understand the atmosphere of DeLand, Florida,” he said in a phone interview from his home in Atlanta. “DeLand, Florida, in terms of Black economics is not very high. In fact, there was a club where we students used to go hang out on the Black side of town. To this day, I swear it had a dirt floor. … Here I am under those conditions and you know I finally got to the point where I said, ‘I give up. This is not for me.’”

Added Johnson, with a laugh, “Frank was a militant. We had to warn him: Tell us if you’re going to do something, so we can get away from you and we don’t get kicked out. He could afford to go anywhere. He had money. But we needed scholarships to graduate.”

A year after the men arrived, Stetson admitted six African American women, including Johnson’s future wife, Dorothy Pompey Johnson. She majored in math and had been head of her class at the segregated all-Black Roulhac High School in Chipley in the Florida Panhandle.

“I didn’t have any problems. I was not called names,” she said, adding the white women in her residence hall taught her to play bridge, although they never invited her to eat with them in the cafeteria. “I love Stetson. It was a very pleasant experience for me. You remember where I came from was very much segregated, so I was used to that.”

She later worked for the U.S. Geological Survey, analyzing data on computers, before deciding to stay home to raise the couple’s two children. Her younger sister, Mattie Patricia Pompey, followed her to Stetson and graduated in 1973.

“I had a lot of confidence in my ability from high school,” Dorothy said. “I never lost that confidence.”

‘Dramatically Different’

Yellowed newspaper clippings, as well as other documents about Stetson’s integration, are preserved in the university archives, housed in the basement of the duPont-Ball Library.

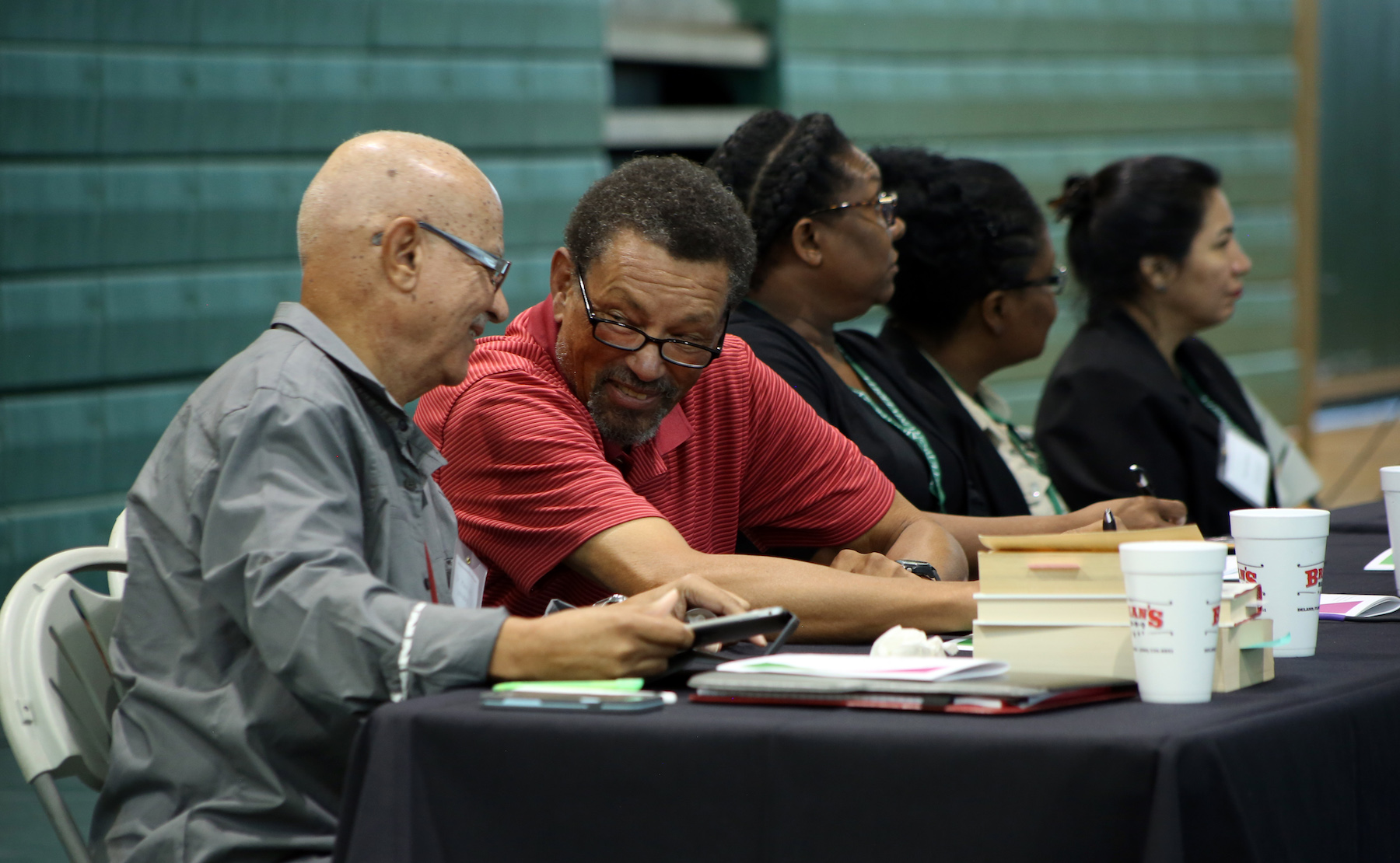

Johnson helps to keep the stories alive, too, through the annual Multicultural Alumni Networking event. As the organizer, he is a bridge, connecting African American students of the 1960s with a new generation of multicultural students.

The event traces its beginnings to 2009, when Johnson’s cousin, Jessica Sally ’12, enrolled at Stetson and invited him to a barbecue for the Black Student Association. It was held in the backyard of the First Year Studies’ office on campus by Dean Leonard Nance, Ph.D., also a university adviser on diversity.

Before Johnson knew it, he was surrounded by a crowd of students asking questions about his career and his time at Stetson. Dean Nance and Professor Patrick Coggins, Ph.D., asked Johnson to return a few months later to talk to more students, and again six months later. The Multicultural Alumni Networking event was born, and soon Johnson was inviting his former classmates to tell their stories, serve as mentors and teach students what it takes to be successful.

“I like having the opportunity to help the young folk get over challenges, to get over obstacles,” said Johnson, who also is a Trustee and chairman of the Men’s Ministry at his church, Mount Calvary Baptist Church of Palm Coast.

Stetson President Wendy B. Libby, Ph.D., has been a big supporter of the event. It was her idea, Johnson added, to provide a nice meal to increase student attendance – and it did.

Speaking at the Seventh Annual event last fall during Homecoming Weekend, Libby said she had recently met with members of Stetson’s Multicultural Student Council, which sponsors the event, along with the Office of Diversity & Inclusion.

“I appreciated their candor and I was also thankful because they felt this campus is becoming a place that’s more open to conversation – sometimes uncomfortable conversation and sometimes just straightforward conversation, and we’re all about that,” Libby said.

She credited the Many Voices, One Stetson program for helping to improve the campus climate. Launched in 2016, the program is part of the university’s foundational priority to “Be a Diverse Community of Inclusive Excellence.”

The Many Voices, One Stetson website notes the university’s “rich institutional history of commitment to civil rights” while still acknowledging that exclusion and alienation based on age, race, religion, disability, gender, sexual orientation and other differences have “marred both United States history and Stetson’s own past experiences.”

“It’s not always easy to understand other people,” Libby said at the event. “If we’re willing to show a little bit of ourselves and learn a little bit about somebody else, we’ve come a long, long way.”

Professor Coggins agreed and said the campus environment is “dramatically different” today for multicultural students. Students find it easier to make friendships across racial lines and the entire Stetson community is committed to welcoming multicultural students. The foundation for change was laid by Johnson and the other students of the Civil Rights Era.

“What I like personally about Jim is that he is able to tell his story in a way that is not bitter, in a way that is not punitive, but in a way that provides balance,” said Coggins, a professor of education and multicultural education, and adviser to multicultural student groups.

“There were people who called him names, but for the most part the president, the faculty, the staff and for the most part students provided support for him. And that’s something I want students (today) to hear, not from me, but from someone who’s an alumnus because that makes a better impression on their lives.”

-Cory Lancaster

–Videos by Bobby Fishbough

“Sharing Their Stories”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2018 edition of Stetson University Magazine (pages 24-29) and on Stetson Today as a three-part series.

Part One: Sharing their Stories

Part Two: Walking in the Forest of Arden

Part Three: Coming Back to Campus

Update Feb. 26, 2019: Story About Desegregating Stetson Wins Award Of Excellence

Update Nov. 4, 2021: Jim Johnson ’68 wins the George and Mary Hood Award in recognition of his commitment and contributions to Stetson and its core values.