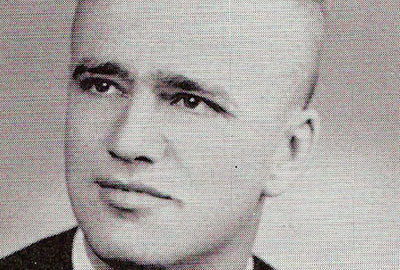

Class of: 1964

Brick: yes

Deceased: 2021-11-9

On 1 June, 1964, I accomplished the biggest goal of my life. I graduated from Stetson University with a B.A. in History and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Accomplishing this goal was the dream of my life. Little did I know that this dream of mine would become a nightmare for me in the decade of the 60’s. Little did I know, then, that the war for which I would later volunteer would become a national disaster and a personal tragedy for me for the rest of my life.

In 1965, I received a deferment from the U.S. Army to go to graduate school at Emory University in Atlanta in American Studies. I did my classwork and finished up in the spring of 1965. I still had to work on my master’s thesis, though, before I could receive my Master’s Degree. Still working on my thesis, I went on active duty 18 October, 1965. By then, the 1st Air Cavalry Division, the unit for which I later volunteered, was locked in battle with North Vietnamese regiments in the Ia Drang Valley. This battle was later featured in a book by Lt. Gen. Hal Moore entitled, We Were Soldiers Once . And Young. The book was later made into a movie starring Mel Gibson as LTC Hal Moore with the title, “We Were Soldiers”. I had asked for the U.S. Army Signal Corps as my assignment in the Army. I didn’t want to be an infantry officer so I joined the Signal Corps. I wanted to be shot at every other day, not every day. After the Signal Officer Basic Course at Ft. Gordon, Georgia, I went to Microwave Radio Officer training at Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey.

In the spring of 1966, I was selected as an aide to the new Commandant of the U.S. Army Signal Center and School, Brigadier General Tom Rienzi. He was a veteran of World War II and Korea. He stood 6’6″ and dwarfed me at 6’2″. We made quite a pair. In the spring of 1967, I volunteered for Vietnam and service with the 1st Air Cavalry Division. In his book about the Vietnam War, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, says he knew by 1967 that the war in Vietnam was lost. He didn’t tell me! Flying out of San Francisco and looking back at the Golden Gate Bridge in the evening dusk, I knew I was in for the adventure of my life. I did not know it would change my life. For nine months, I was a young Lieutenant with the division signal battalion. I was the platoon leader of the unit that handled all of the 1st Cav.s logistics communications in Vietnam. I travelled all over the country based out of An Khe, base camp of the 1st Cav. In January 1968, the North Vietnamese buildup alerted Gen. Westmoreland. He sent the 1st Cav to Hue to make “maximum impact on the population”. Come February 1 and the beginning of the Tet Offensive, the population made maximum impact on us. Sitting astride Highway 1, what the French called “the Street without Joy”, the 1st Cav was shredded in the first few weeks of the Tet Offensive. Its battalions and companies suffered massive casualties. With no supplies coming up Highway 1 and its helicopters having to fly to Da Nang for refueling and in the midst of the monsoon season, the Cav was a sitting duck. On February 1, 1968, I was promoted to the rank of captain. It took three weeks for my battalion commander to even reach me to pin my bars on. I had to fly back to Da Nang and get my own liquor. My promotion party was in a blacked-out tent in the middle of the monsoons outside of Hue. Before the Tet Offensive, I wanted to go down to an infantry battalion to be its communications officer. That billet was a captain’s slot and I would be a captain soon. Some 5,000 Marines were under siege at Khe Sanh and I wanted to be part of the rescue mission that I thought would be the turning point of the war. It would be the set piece battle the French were looking for, which turned out to be Dien Bien Phu, a disaster that ended the war for the French. I thought the battle for Khe Sanh could end the war favorably for us. With the chaos surrounding the Tet Offensive, I lost my courage. I wanted to get out of the orders sending me out to an infantry battalion. The orders stood. In early March, I was sent to the 2nd/12th Infantry Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 1st Air Cavalry Division. During the Tet Offensive, the battalion had lost almost half its men. Its communications equipment was so shot up I had to set out on scrounging missions with my friends at division signal for enough communications gear to lift off for Khe Sanh.

On the evening of March 31, in the United States, it was already April 1 in Vietnam. That was D-Day for Operation Pegasus, named after the flying horse of mythology. The fact that the 1st Air Cavalry Division was lifting its entire division by air into the hills two clicks east of Khe Sanh made the title of the operation poignant. We were, indeed, the flying horse coming to the aid of 5,000 U.S. Marines at Khe Sanh. However, at exactly that moment in the States, Lyndon Johnson was declaring a U.S. bombing halt in the northernmost portion of North Vietnam and announcing he would not run for the Presidency again. As one French lieutenant put it serving in Indochina in the 1950s said, he felt he had been “punched in the stomach and knifed in the back”. That’s exactly how I felt. On D-Day, April 1, 1968, the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division lifted off from Dong Ha for Ca Lu, nicknamed LZ Stud, fifteen clicks east of Khe Sanh. How appropriate to name the part of the horse that was hung out the most. The next day, they assaulted into the hills two clicks east of Khe Sanh. My brigade and battalion air assaulted April 2nd into Ca Lu. The next day, we air assaulted into the hills two clicks east of Khe Sanh. As I got out of the chopper scared for my life, I took a quick glance down at the Khe Sanh base. It was surrounded by a moonscape and B-52 bomb craters. I quickly put my signal team in the bottom of a B-52 bomb crater.

The night of April 4, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in the United States. That same night we were attacked by the NVA using Russian made 122mm rockets fired from Laos. Four men on the hill were killed and I was smattered with debris. The morning of April 8, 1968 was full of sunshine and good weather. Our air power could finally provide the cover we needed. I was asked to set up a radio relay team back at Ca Lu. I volunteered to lead the team. Arriving at LZ Stud at midmorning, I leapt under the helicopter blades. As the chopper took off, I saw a grenade lying on the ground. I thought it had dropped from my web gear. With my M-16 behind my back in my left hand, I reached with my right hand to pick it up. I was 5 inches from the grenade when it exploded. I lost my right hand and my right leg instantly. My left leg was amputated within the hour as I was flown by medevac to a Quonset hut field hospital on the seacoast. Years later, I discovered that it was not my grenade at all. It had been dropped by an enlisted man when we were unloading the radio team. Apparently, I found out later, he had loosened all the pins on his grenades and was a walking bomb. After 45 pints of blood and five hours of surgery, I was kept alive. Over the next two weeks, I was flown by medevac to Da Nang, Thuy Hoa, Cam Ranh Bay, Japan and, finally, to Walter Reed.

By late April of 1968, I finally was in the United States. I was missing two legs and a right arm and faced an uncertain future. On June 10, 1968, my mother stood in my place and accepted by Master.s Degree from Emory University. On 23 December, 1968, the day before Christmas Eve, I received my medical retirement from the U.S. Army. The next year would see me get out of Walter Reed, go the Washington, DC VA Hospital and, finally, to the VA Prosthetic Center in New York City. Christmas 1969 found me in in my parents. living room in Lithonia, Georgia, wondering to myself, “What the hell do I do now?”