Class of: 1965

Email: [email protected]

Upon graduation from Stetson University in January, 1965, I was commissioned from R.O.T.C. as an Army Reserve 2nd Lieutenant with an active duty reporting date of May, 1965 to the Infantry Officer’s Basic Course (I.O.B.C). The Infantry Officer’s Basic Course is really a finishing school for lieutenants who have already been assigned to their branches such as armor, artillery, engineer, or as in my case, Fort Benning, Georgia, for Infantry school. By May, the United States was already sending Special Forces soldiers to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand, and a number of my classmates in I.O.B.C. were already assigned to the First Cavalry Air Mobile Division that was being formed as a new concept for the old horse soldiers who were once lead by General George Custer. The new concept in infantry warfare was going to be helicopters and the ability to be quickly to the fight and/or deployment by rotary wing aircraft.

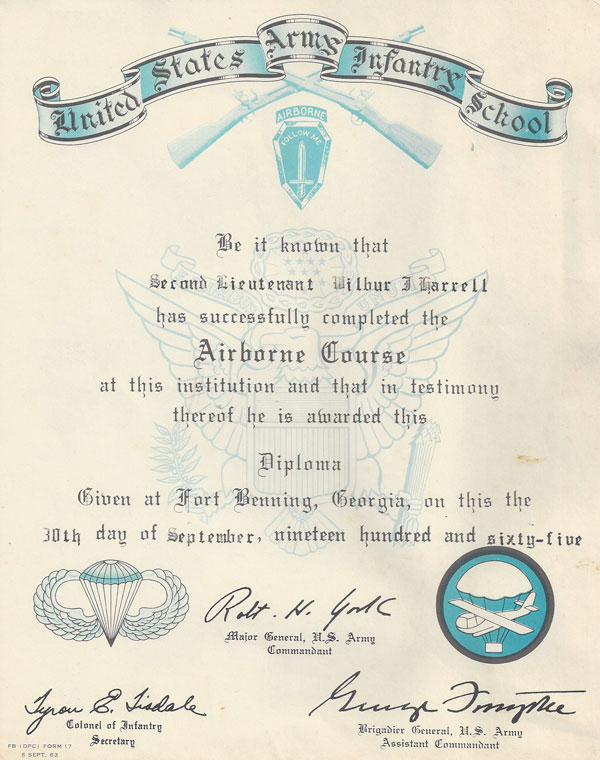

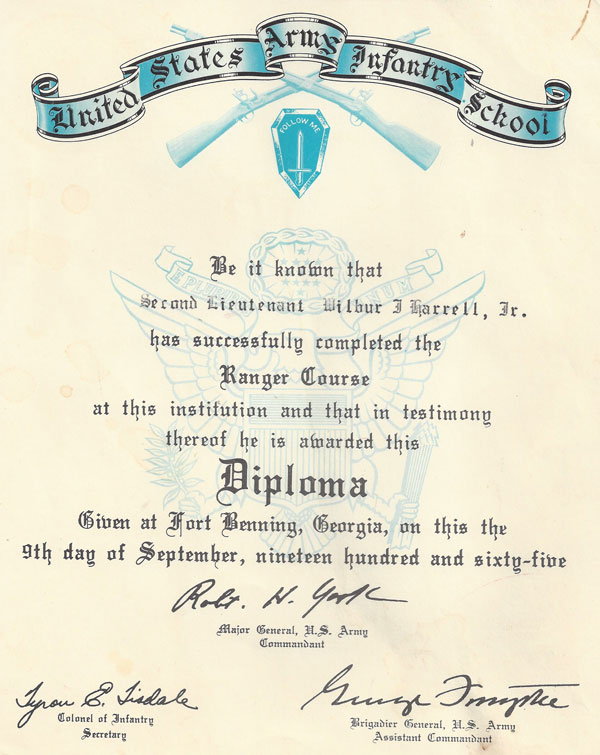

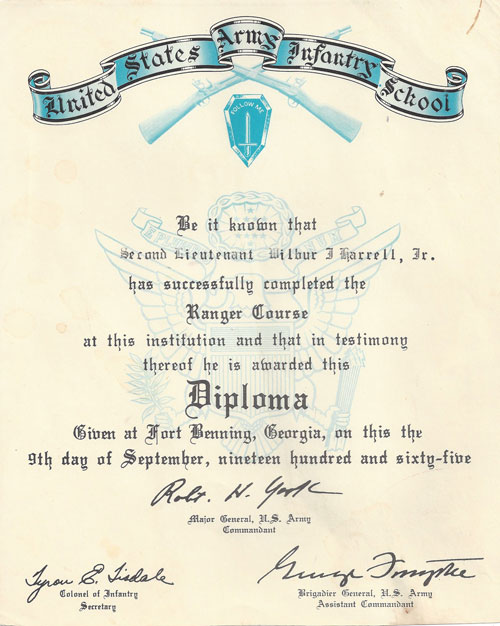

However, my first set of orders dictated that I would be deployed to Korea for a 13-month hardship tour (with no dependents). I’ll never forget my orders for deployment as my address was A.P.O., San Francisco, CA 96220. After consulting with my R.O.T.C. instructor, I found out that the A.P.O. stood for all points overseas with a zip code to the Frozen Chosin (a famous river in South Korea). During my nine weeks of finishing school (I.O.B.C), some were offered an opportunity to volunteer for Army Ranger School, a nine week leadership course also at Fort Benning, where one could earn the coveted Ranger Badge. (It didn’t make you bullet proof, but it looked good on your resume.) With this training, one becomes very well trained in skills such as hand-to-hand combat, mountaineering, and swamp survival. Also, the opportunity to become an Airborne Soldier or paratrooper almost guaranteed, upon the completion of jump school, the assignment to one of the elite and combat ready units in various places such as Fort Bragg, NC, with the 82nd Airborne Division or the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, KY.

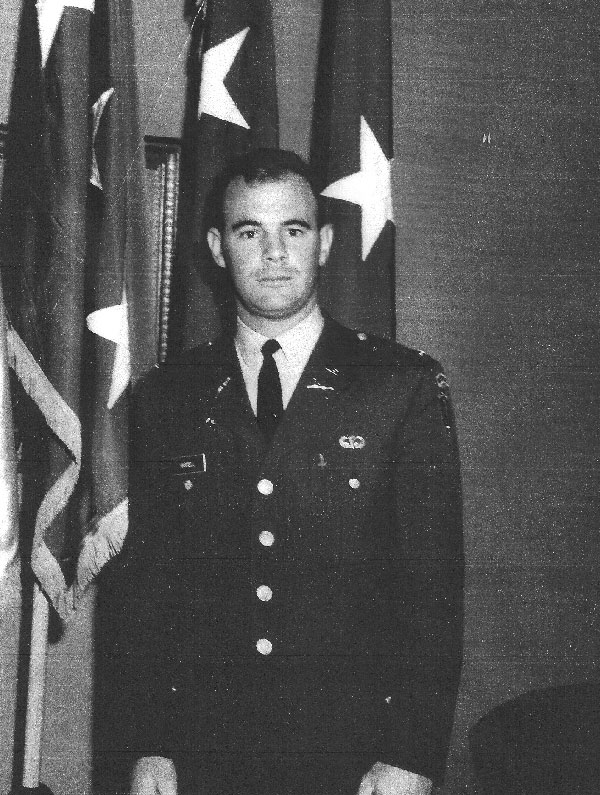

By the end of my 21 weeks of special training (I.O.B.C., Ranger School for nine weeks, and then Airborne School for three weeks and five jumps), President Lyndon Johnson had reinstated the draft. My orders were changed from Korea to Fort Benning where I would become an instructor. Upon completion of basic training, the draftees we were training were going to be assigned to Vietnam, advanced infantry training, or another branch such as communications, vehicle maintenance, or medical service corps. I was assigned, with another lieutenant who thank goodness was an engineer, to an area of Fort Benning called (appropriately) Sand Hill. Sand Hill had not been used as a training site since World War II, and the barracks were not air conditioned, even though they had running water and screens on the windows. We transformed almost 200 acres of Georgia Pines into training ranges for various fighting skills. One morning after introducing myself to the trainees and briefing them on what they would be learning that day, a brand new recruit came up to me, saluted and said “request permission to speak, sir.” I immediately returned his salute and said “drop down and give me ten pushups.” After completing his task, I said “at ease, soldier” and we shook hands. He was a fellow classmate from Stetson and had been drafted in 1965. His name was Ty Wilson, also a Floridian and member of Pi Kappa Pi fraternity. After almost a year at Fort Benning and only wearing fatigues and moving a lot of draftees through training, I was surprised by a phone call one Saturday morning from the duty officer at the training center to report to the Commanding General’s Office at 0800 hours on Monday morning. The Commanding General was also the Commandant, a two-star general and West Point graduate. My first reaction was “Oh _ _ _ _” , I’m being court martialed. The duty office, a captain, said I was interviewing for a position on the General’s staff. Needless to say, I was surprised at being nominated – not being a West Pointer or as they (West Point grads) were called – “ring knockers.” Upon being commissioned as a second lieutenant, I was required to buy a Class A Uniform (the Army’s equivalent of a business suit) and a set of dress blues (the Army’s equivalent of a tuxedo). Prior to that phone call, I had never had a occasion to wear my Army coat and tie – much less an Army tuxedo. Thank goodness every newly commissioned officer was given an Officer’s Manual, which showed what went with this or that and where our name tag and rank were to be attached to the uniform. I quickly had my Ranger Badge and Jump Wings affixed to my Class A uniform.

On Sunday, I made a reconnaissance drive to be sure I would show up at the right place and in the correct uniform. The following day I was more nervous than when I made my first parachute jump. On Monday morning I reported to the Secretary of the General’s Staff, a full colonel who had fought in World War II, Korea, and the Dominican Republic with the 82nd Airborne to free many American students who were being held against their wishes. I had not seen that many ribbons on one uniform in my short time in the service, and I was duly impressed but also very intimidated. He promptly returned my salute and said “at ease and have a seat, lieutenant.” As fate happened he was retiring soon to the Cocoa Beach, FL, area and he wanted to know about Patrick Air Force base and, naturally, the commissary. He actually knew where Stetson University was and saw from my brief resume that I had entered the service from South Florida. He said “my wife and I would like to know about Melbourne, Eau Galle, and the surrounding communities. We can teach you about the important position you would be occupying on the General’s staff.”

My orders were changed on the spot, and I became the new protocol officer in charge of all visiting foreign dignitaries who would be coming to Fort Benning, GA in the next twelve months. Guess what – I never wore fatigues again until summer camp as a reservist in civilian life. I wore out my dress blues as I had a formal function at least once a week and sometimes more frequently depending on who was visiting Fort Benning. Fort Benning has the School of the Americas and trains officers from many South American countries as well as from Canada, France, Germany, and other friendly places in the world. Sadly, there are fewer officers from the Middle East and a lot less from other countries than there used to be. While I never lead a platoon of soldiers into combat against an enemy nor fired a shot while securing an objective or had anyone die on my watch, my service was important and meaningful. My good friend and classmate, Max Cleland, said “you were just at the right place at the right time, and you wore the uniform with honor and spirit.” It has taken me some years to be at peace with my fate and all of the training paid off as I served my country and I am proud of that.

Several attachments and photographs are included along with a letter from one of the visiting dignitaries who came to Fort Benning while I was in charge of visiting foreign guests. Copies of my certifications for completion of the Airborne and Ranger courses are also included.